Allergic to being still: A runner’s diary

The most trustworthy source of food and

fitness journalism in the country.

Editor’s note : In a world where self-help content often promotes quick-fixes and bite-sized habit-building tips, it is easy to forget that the path to fitness is rarely linear. It is a complex and nuanced journey, with unexpected highs and lows that vary with what’s happening in our lives.

Today, we are publishing Shantanu Kishwar’s refreshingly honest essay on running, which captures the multifaceted nature of fitness journeys as he describes the various phases, from apathy to inspiration to obsession and uncertainty. His essay serves as a reminder that there is no one-size-fits-all solution to personal fitness.

Shantanu is a freelance writer and works at the WageIndicator Foundation. You can follow him on Twitter and subscribe to Multitudes

1. Indifference

At the age of 14, the crowning glory of my nonexistent athletic career was coming second to last in a 600-metre race.

I remember the day quite clearly. It was a winter morning in 2010, and as we neared the finish line, my closest competitor was a fair bit ahead. I’d resigned myself to last place; by that point, my breathing was becoming faster, but my legs were slower.

And then, the miracle. A heaven-sent second wind spurred me on. My legs galloped as we rounded the final curve. The gap shortened. He was taking it easy. He — and everyone else — didn’t expect me to catch up. But, powered by my galloping legs, I stumbled past him. He didn’t have the time to wipe the confused look off his face and chase after me. I crossed the finish line with an adrenaline-dopamine-serotonin-powered smirk, basking in the knowledge that over 600 metres, there was someone just a tad bit slower than me.

Clearly, I wasn’t fond of any strenuous exercise. I attended cricket practice at school, but this was when athleticism was peripheral to the game’s concerns (Virat Kohli’s fitness revolution was still a few years away). My teammates and I jogged before sessions as a formality, as if to prove that we were indeed part of a sporting endeavour — just not a serious one. I don’t think I ran more than a kilometre until I was 18. I certainly never enjoyed it. When it came to playing the game, I cut the figure of a very round child chasing after a very round ball.

2. Change

At the age of 18, after my first year of undergrad, I wanted this to change.

I was very overweight and felt odd aches across my body. More than anything, I was tired of seeing a fat kid in the mirror because of body image issues inflicted by years of minor bullying in a preppy Delhi high school. I was sick of my round face making me look like a child throughout my teenage years and classmates saying I was “lactating” from my “man boobs” when I spilt water on my t-shirt.

It may not have been the healthiest motivation to lose weight, but it finally got me to act.

I don’t know why, but as much as I hated it, I thought I had to run to make this happen. It felt like the price of admission to the Club of Healthy People. So, I begrudgingly started making rounds of my neighbourhood in Delhi. I doubt I moved faster than I walked initially, but I certainly swung my arms and legs a lot more.

Ultimately, at the end of that first summer of my undergrad, a combination of running, cycling, yoga, and dieting saw me lose about 15 kilos. It wasn’t the healthiest weight loss, but it felt worth it when, on my first day back, a friend said, “Damn Kishwar, you’ve got a jawline!”

Academics kept me busy during college, which meant working out only during summer breaks, starting from scratch each year. A friend and I would start around 9:30 at night: run, try some callisthenics, finish by 11, and have dinner at midnight. This was my routine all summer long. I didn’t set any running goals. The concept of even remotely long distances still escaped me. It took my four years of on-and-off running to push myself to a 3k — the first time I ran that, I felt like I’d finished a marathon. I didn’t think it was ever physically possible for me to go further.

And then, a chance encounter in 2017 changed it all.

Like what you see so far?

Get TBT articles in your inbox every Saturday

3. Inspiration

It was on my first solo trip. I’d just graduated from college and travelled to Ooty to beat Delhi’s summer heat. In a hostel there, I talked with a fellow traveller who’d come there to practise hill runs. He’d been a marathoner for years and was now venturing beyond even that, prepping for an 80km race through the mountains of Ladakh. I thought him clinically insane but also slightly inspiring.

We talked extensively, covering books, travel, and more during a 22 km walk along the train tracks from Lovedale to Coonoor. What stuck with me was how he spoke of running.

It seeped into every part of his life. His days were planned around long runs, and his work around long races. He didn’t do it for glory. He did it because he wanted to run, living by the same attitude Haruki Murakami professed in What I Talk About When I Talk About Running:

“People sometimes sneer at those who run every day, claiming they’ll go to any length to live longer. But I don’t think that’s the reason most people run. Most runners run not because they want to live longer, but because they want to live life to the fullest. If you’re going to while away the years, it’s far better to live them with clear goals and fully alive than in a fog, and I believe running helps you do that. Exerting yourself to the fullest within your individual limits: that’s the essence of running, and a metaphor for life—and for me, for writing as well. I believe many runners would agree.”

Somewhere along that walk, this became something I aspired to. A few months later, I read Born to Run, the runner’s Bible by Christopher McDougall, and this urge was pushed into hyperdrive.

The book’s argument was simple: our bodies, right from the arch of our feet to the size of our glutes to ligaments that hold our heads up straight, are designed to run. I was taken in by the outlandish feats it documented of humans powered by nothing but willpower and mild insanity: people running 100+ mile races in Death Valley and Mexican tribespeople that ran 50 miles in one go like it was nothing.

If McDougall said that humans were biologically engineered to run, then run, I would. It mattered diddly-squat whether I enjoyed it, which I still didn’t. I bought into delayed gratification; I knew I’d feel good after a run, so I drowned out my body’s protests with podcasts and music, taking one step at a time.

4. Progress

By then, I was done with college and living in Delhi with my parents. I was trying to embrace the runner’s lifestyle, but the gap between intention and action didn’t miraculously disappear. I ran once or twice a week, pushing myself further every time. I wasn’t suddenly completing marathons, but I moved from a personal best of 3k to 4k and then 5k. In March 2018, I did 7k on the slopes of a hillside, no less.

In February 2019, I overcame my fear of double-digit distances, signing up for and completing my first 10k. It meant running for an hour, which seemed like an eternity. Yet on a winter morning with the temperature at 6°C and an AQI of 200, I set out with a few thousand others and did just that.

I finished with a time of 54:30 and, for the first time, felt proud of what I’d achieved.

I’d somehow gone from being a round child stumbling through 600 metres to a less-round adult finishing a 10k at a decent pace. I’d spent years being angry at myself for being overweight and unfit. But I didn’t want that to be my destiny and ensured it wasn’t. I had achieved this. I set a goal and followed through. My athletic career had a new crowning glory.

Consistency still eluded me, though. At the start of every year, I set myself a target of 520k for the year or 10k a week. This was easy enough to achieve in any week but harder to sustain over time. A one-day break inevitably turned into a one-week break and then a one-month break. Before I knew it, a small pause that started in March ended only in November.

5. Introspection

Fast forward to 2022, and familiar patterns played out. The 520km target was set and forgotten by mid-Feb.

Around October is when, for the first time, things really changed.

After severe burnout from my last job, which had me work twelve hours a day, six days a week, I wanted to take care of myself. My sleep was terrible, my resting heart rate was high, and my clothes were tight. As the fog of anxiety from that job lifted, I realised I couldn’t go on like this.

All the white pop-culture pundits of good health — Rich Roll, Peter Attia, and Andrew Huberman — convinced me that changing my lifestyle would be worth it. It meant more than exercise: I’d also need to eat healthy and sleep properly.

And so I committed to a better version of myself, devoting my time, energy, and money.

I resumed running but also got a year-long CultFit membership in October to add strength training and yoga to the mix. Little did I know that I’d come to regret that decision.

Like what you see so far?

Get TBT articles in your inbox every Saturday

6. Injury

In my first strength training session at Cult on the 6th of October, poor form and over-exertion left me with a dull ache in my lower back. I assumed it was dormant muscles voicing their protest and ignored it. After a dance fitness session the next morning, that pain grew. By 2 PM that afternoon, I couldn’t move.

In four hours, my lower back turned into a single, solid brick. Pain radiated up my spine and down my legs. The tiniest motion had me gasping. If hell existed, such agony surely was a staple of suffering there.

I stood up thrice in 24 hours to use the bathroom, hunched over, grabbing everything I could for support. I lay on my stomach throughout, turning my head sideways to shovel food into it at meal times.

I later discovered there was a bulged disk in my spine pressing on my sciatic nerve, which I’d caused by pushing myself harder than my core could handle.

Surprisingly, and fortunately, the recovery was almost as drastic as my collapse into pain. In ten days, I could walk long distances. In a month, I felt like I was physically back to my old self.

Mentally, though, something changed.

7. Obsession

Lying in bed while injured, I was frustrated and angry. I was trying to do the right thing. The hard thing. Every fibre of my being wanted to push itself and be tired after a good workout. I was rebelling against the convenience of a world designed for sedentary living. Yet, all my good intentions got me were severe pain, huge physiotherapy bills, and a prescription to lie in bed.

This frustration also brought clarity. This isn’t how I wanted to spend my life. I’d taken the ability to move, walk, and run for granted. I assumed that I’d always be able to be active. Now, the privilege of a healthy body stared me in the face, forcing me to cherish it.

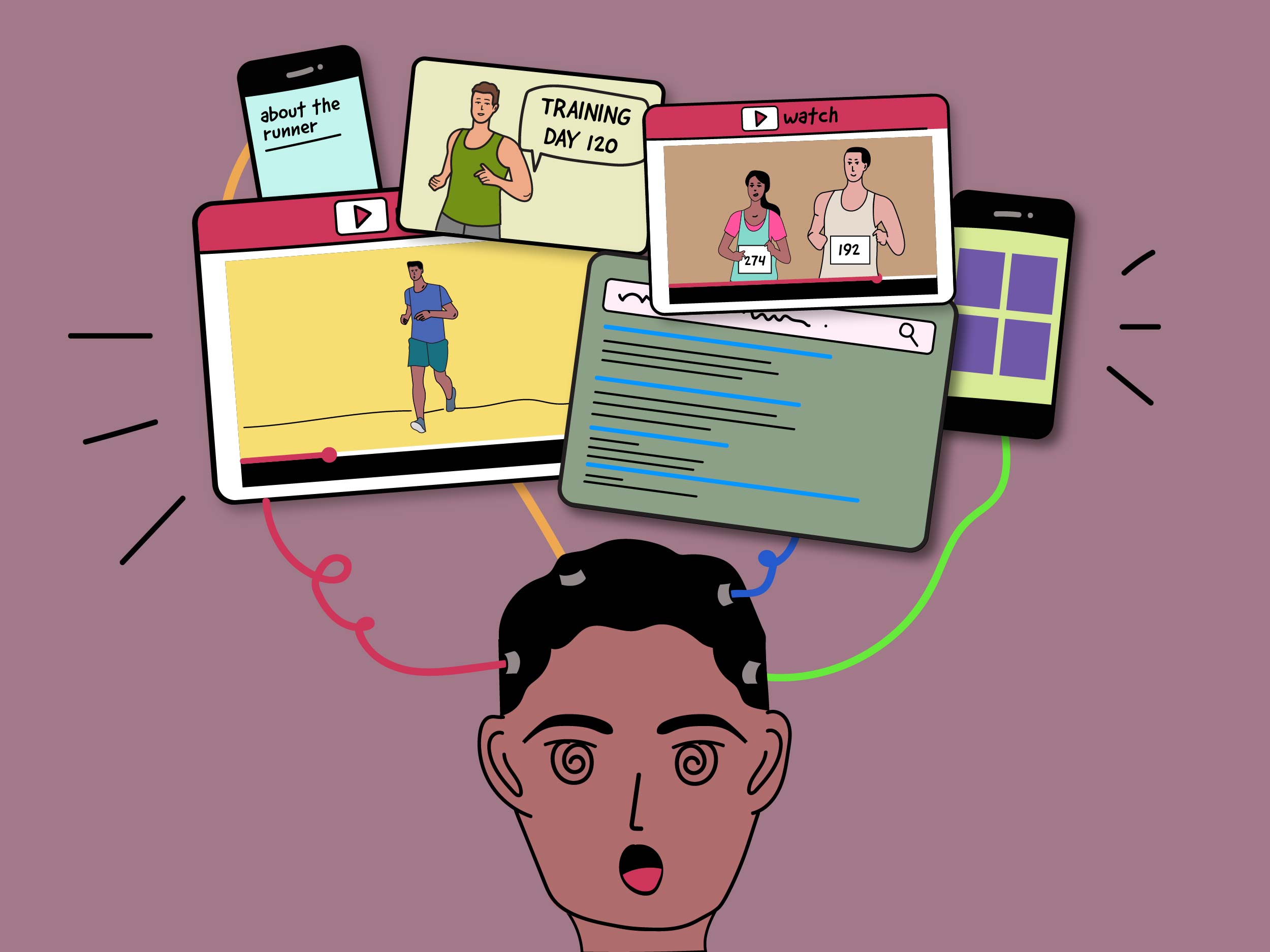

Those days spent bedridden were filled with inordinate amounts of screen time. Since I couldn’t run myself, I lived vicariously through those who broadcast their running on YouTube. Hellah Sidibe, Kofuzi, and Casey Neistat became a steady company.

Casey’s videos, more than anything else, got my feet tingling and my soul roaring. Unlike Hellah and Kofuzi, he wasn’t a professional runner. He had enough and more keeping him busy, from his filmmaking career to his family.

Despite this, he laced up his shoes every morning and ran to keep his sanity intact. It was a non-negotiable part of his day and life.

The best part? He’d done this despite an accident that shattered part of his leg and after doctors told him he’d never run again. He’d come back from that. What was I worried about?

He brought me hope when all I saw was frustration and anger.

Two videos, the ones above and below, nearly brought me to tears. They were less than 5 minutes long together, but they changed me. I saw someone who understood, as I now did, that the ability to run was a gift that couldn’t be taken for granted. It was a gift that gave the more you committed to it.

A switch flipped, a bulb went off, whatever. Instinctively, I knew I didn’t force myself anymore. It wasn’t a choice. I finally felt like a runner — so I would run.

8. Action

I started moving again as October turned to November. Short walks became long walks which turned into short runs and then long runs. Even during a month of travel, which would have been an excuse to stop earlier, I stuck with it. My baseline had become a 30-minute/6k run, double what it had been any time before.

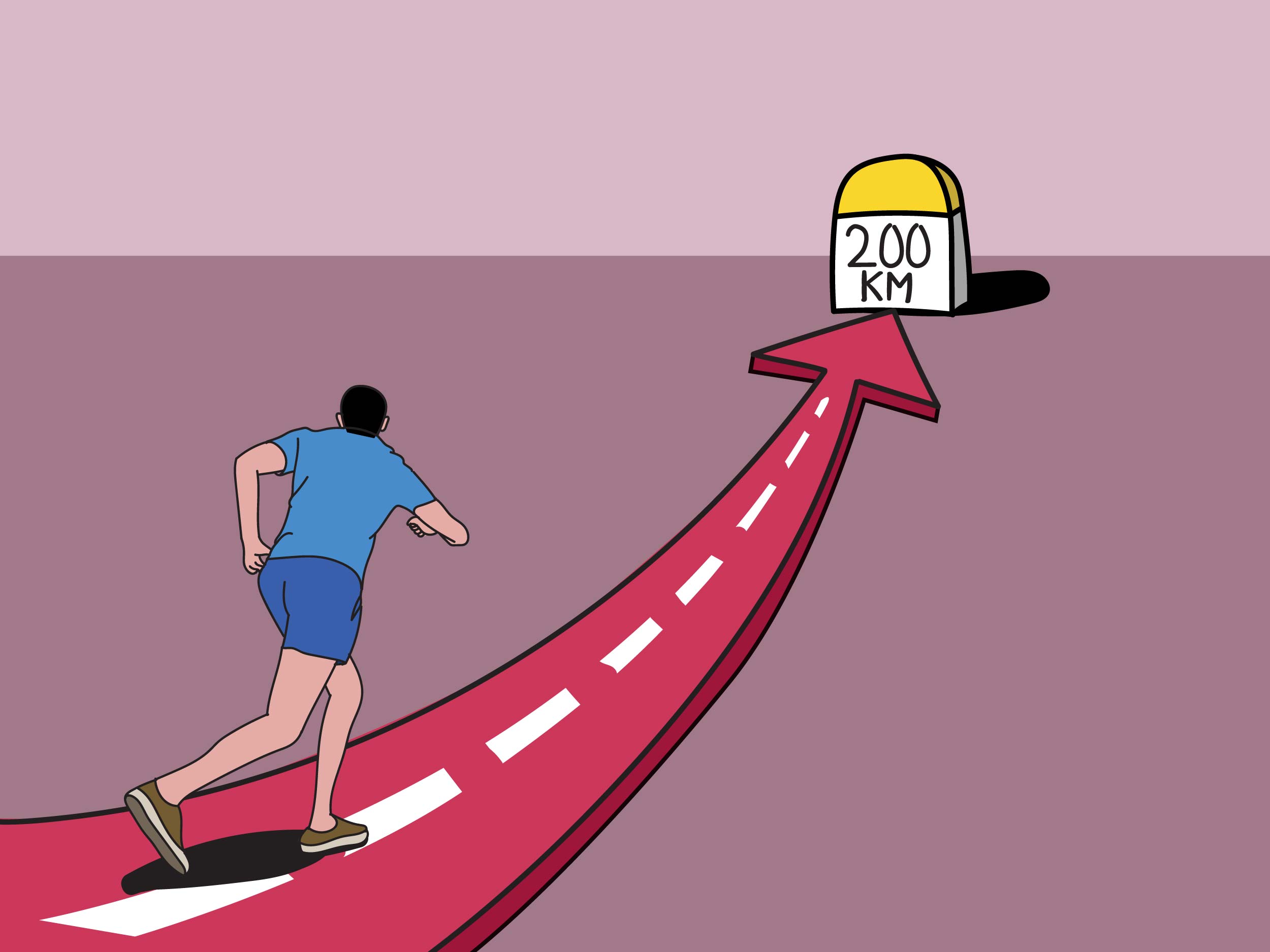

I wanted to end 2022 on a high, so I gave myself a goal: 55 km in December to hit 200 km for the year. It wasn’t a massive goal, but it was more than I’d run in a month for a long time. It would demand consistency; I’d need to run thrice a week to hit this.

Most importantly, it felt like enough to get momentum going for 2023, a year in which I saw running being a non-negotiable part of my daily routine.

Running post-injury felt different. As I made my way through those 55 km, I’d listen to podcasts, music or nothing for the first time. I’d give myself questions to ponder, letting thoughts run through my head as I ran around my neighbourhood. I was smiling while running, not after.

Earlier, running always felt more mentally taxing than physically. Now, my mind was in sync with my body; it stopped protesting the next kilometre, didn’t want to quit short of my target, and didn’t force me to obsessively check my Fitbit to see how long I had left.

I was on course to hit the 200km mark for the year. By the 28th of December, I was 49 km through my 55 km target for the month.

That day, I set out for the remaining 6k to hit 200 and smiled as I made my way down sunny, tree-lined lanes. I felt happy, hopeful and fulfilled.

Just for that moment, the world was perfect.

But that idyllic moment didn’t last. I never made it to 200.

Like what you see so far?

Get TBT articles in your inbox every Saturday

9. Injury (Again)

My lower back seized up just after the halfway mark on that “perfect” 6k run. It was a disturbingly familiar pain. The ghost from October returned to haunt me. The momentum of my increasingly energetic legs slammed against the brick wall that was my dysfunctional spine.

I stopped running immediately, ambling home with a single thought: “Please, God, not again.”

But, again, it was.

I reached home, got into bed, and stayed there for the better part of two weeks. When I eventually emerged, my doctor showed me an MRI of my spine and told me my core wasn’t strong enough to negate the constant shocks running on roads sent up my vertebrae.

My last goal for 2022 fell apart and, at that moment, took away all hope I had for 2023. In a week, I went from humble bragging about a personal best 10k time to saying, “I could walk a little today with the help of a crutch.”

These words had no business coming out of a 27-year-old body, but they were. I felt betrayed by the universe, punishing me again for wanting to be healthy.

I’d done what every self-help book had told me to. I’d built habits, been consistent and really wanted to be better. But no matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t. Instead, I was forced back into bed and left to contemplate the prospect of spinal surgery.

It felt like I’d lost all hope of being a physically active person. I was terrified by the fragility of my body. I couldn’t trust it — a wrong step anywhere could land me back in bed.

Both times so far, I’d been walking distance from home when I got injured. What if the next time I was alone on holiday in a strange place?

That gloomy fog lifted, eventually. Aided by a steroid shot in my back, in three weeks, I was functioning like someone with a (mostly) normal spine. My doctor deemed surgery unnecessary and told me that if I diligently strengthened my core and avoided running for a while, I could return to my best in about two years. This feels like an eternity, but three years of COVID passed in the blink of an eye. I’m sure these also will.

And because I’m a sucker for meaning-making, I’ll concede that these bouts of bedriddenness have taught me a fair bit.

10. Uncertainty

In October, I realised I was allergic to sedentary living. Indifference to good health was a thing of the past, and I didn’t need body image issues or miraculous inspiration to motivate me anymore.

The convenience of staying put was nothing compared to the happiness I felt when I really exerted myself at the end of the day. Every kilometre I ran felt like a barrier broken. Every day I exercised, I felt myself moving towards a version of myself that lived a longer and better life.

If that was October’s lesson, December taught me that I couldn’t be pig-headed when trying to be active. If the highway to hell is paved with good intentions, so is the path to my orthopedist’s office. Being healthy still matters to me — now more than ever, in fact. But I’ve learnt that exercise, if done poorly, can also be the enemy of good health.

These are simple lessons, but if they had to be learned, I’m glad I’m learning them at 27.

My doctor also wants me to run again, eventually. I don’t know how to feel about that. After everything that’s happened, running is no longer the object of my obsession it was a few months ago. It exists hazily in my periphery, bearing the aura of a poisoned chalice.

It has so much to give but maybe, even more, to take away. It’s a game of Russian Roulette, with equal chances of dishing out either ecstasy or agony. At the moment, I’m too terrified to pull the trigger.

Eventually, I suppose. It’s better than never. For now, that’s good enough.

Click the logo to sign up for the newsletter