Did we need Poonam Pandey’s shock-marketing on public health?

The most trustworthy source of food and

fitness journalism in the country.

Editor’s note: Dear readers, hello on a Tuesday evening—we’re making an exception and publishing this mid-week because there’s an important conversation in the news on public health—actor Poonam Pandey faking her death to raise awareness on cervical cancer. Rampant outrage followed. Was this approach justified? Did the ends justify the means?

Today’s thought-provoking opinion piece by Anoo Bhuyan turns the lens around and asks us—the public—to reflect on our own reactions: have we become too desensitised to death?

Anoo, who currently heads Media Labs at The Whole Truth, brings her extensive experience as a public health journalist with major outlets, including Outlook Magazine, The Wire and BBC. You can follow her on LinkedIn here.

One of India’s more successful public health campaigns has been “Do boond zindagi ki” for polio eradication and “TB harega, desh jitega” for Tuberculosis prevention — both anchored by our national father figure, Amitabh Bachchan.

On the TB campaign, Bachchan came out in public and spoke about how he had contracted TB and had been a carrier for eight years, without quite knowing it. On polio, an oft-repeated story is that mothers were so moved by Bachchan taking an angry scolding tone in the ads, that they got their babies inoculated to keep him from being annoyed.

Because disease and death burden in India is so high — anything that happens in India will always happen at scale — the government found it hard to move the needle on both polio and TB.

That’s why they needed the big guns (Piyush Pandey, Amitabh Bachchan, Ogilvy, DDB Mudra and others) to come up with these campaigns to move the rest of us, to act on these diseases.

Now that we have “dealt” with TB (Edit: We have not — India still has the highest TB burden globally), what can we move on to?

Cervical cancer, perhaps?

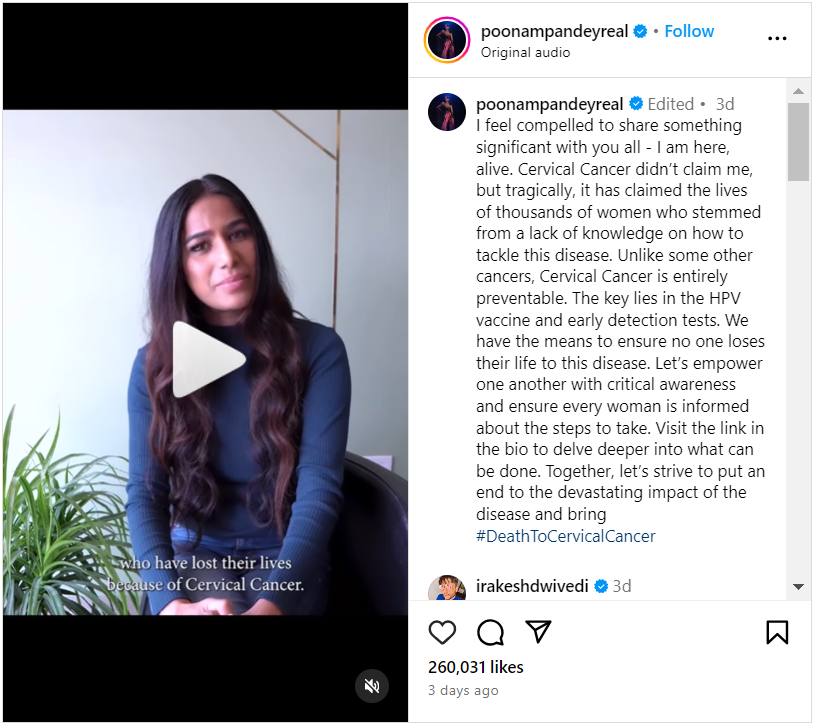

On February 2, for the first time in a long time, cervical cancer got its due, when Poonam Pandey, an actress and celebrity, was pronounced dead on her Instagram account, which said she had died from cervical cancer. Until the next day, when she posted a video saying she was in fact alive and had faked her death to raise awareness of the disease.

Did we need this shock-marketing on public health?

Poonam Pandey in a video to say she had faked her death to raise awareness on cervical cancer.

Cervical cancer at scale

India accounts for a third of all cervical cancer deaths globally, with 1.3 lakh cases diagnosed annually and about 70,000 deaths. It’s also the third most common cancer in India, making up 17.7% of all cancer cases here.

However, unlike many other cancers, cervical cancer is largely preventable with vaccines to protect against the Human papillomavirus (HPV), the primary cause of this disease. These vaccines work by protecting against the most harmful HPV strains known to lead to cervical cancer, thereby significantly reducing the risk of developing the disease.

There are three brands of HPV vaccines in India for the prevention of cervical cancer: Gardasil-4 and Gardasil-9 which provide protection against different types of the virus. It costs Rs 4000 and Rs 11,000 per dose. There’s another brand, Cervarix, which costs between Rs 3000 to Rs 6000 per dose. And very recently, there’s Cervavac, made in India, at Rs 2000 per dose. Women have to get three shots of these vaccines. Which brings a vaccine bill of Rs 6000 to Rs 36,000, depending on which of these vaccines you take.

And yet, I hadn’t Googled this or bothered to get myself this vaccine, until this week. I’m a 32-year-old woman. And as a journalist, I have spent the last many years fairly steeped in the public health conversation. It shouldn’t have taken this extreme event in the media for me to have done this.

In fact, on 31 Jan, just two days before the Poonam Pandey stunt, India’s finance minister announced in the interim budget, that the government would “encourage” vaccinating girls aged 9 to 14 years, against cervical cancer.

But did this announcement get any of us to wake up, shake up, and consider getting ourselves, our sisters, daughters or mothers vaccinated? Men can also get cervical cancer and should take the vaccine. But did the announcement make ME think of getting the vaccine?

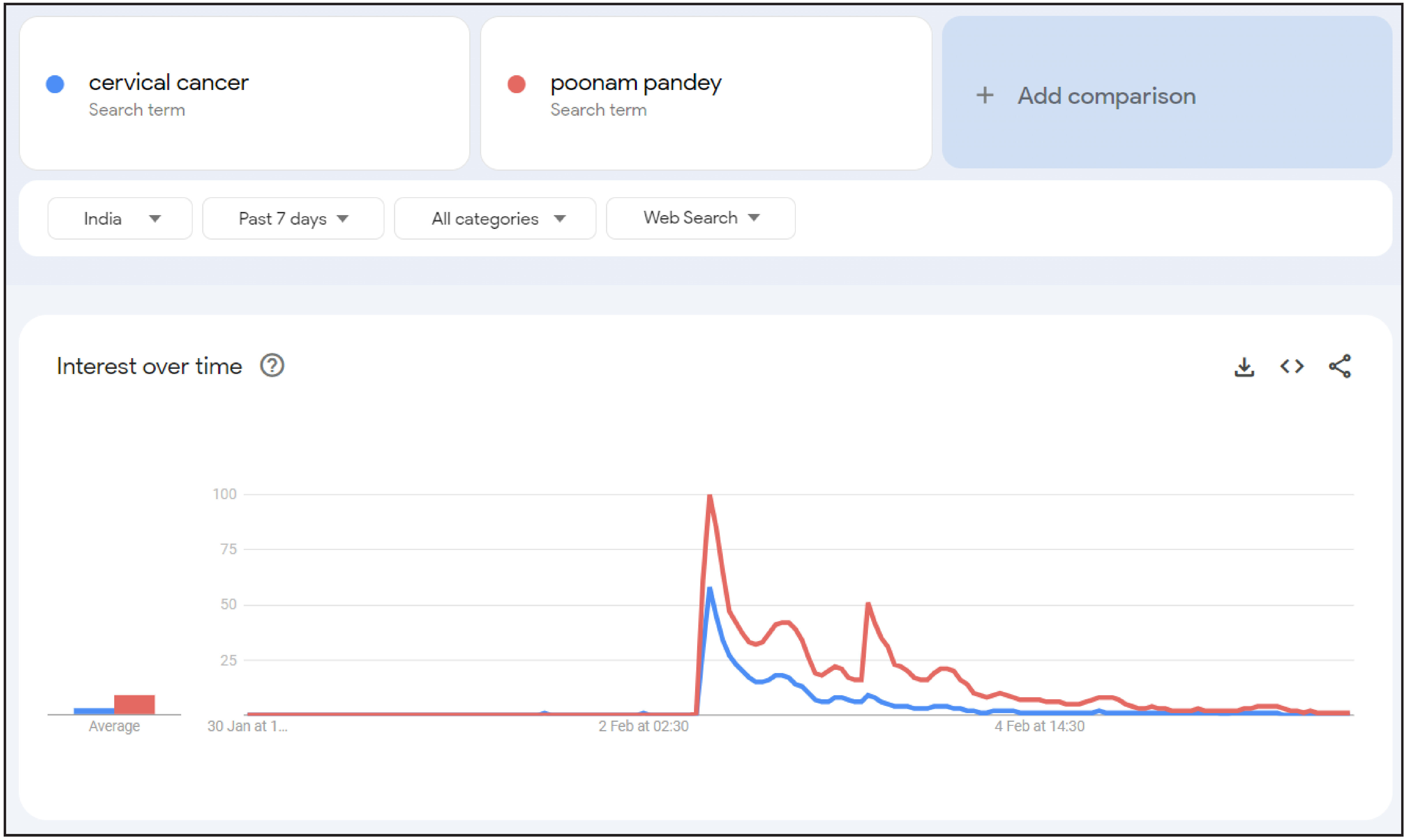

Nope. None of this happened until Poonam Pandey’s Instagram announced that she had died from cervical cancer. Her dramatic approach appears to have successfully captured public attention, as evidenced by the sharp increase in Google search queries for ‘cervical cancer’ coinciding with her stunt.

Give sharing and the vaccine a shot 💉

“We hope this doesn’t happen with anyone else”

Segway with me into what it’s like to have a ringside view of public health in this country. I spent many years specifically covering public health. It meant tracking tragedy, landing up there and following up on it.

Covering public health has been one way for me to understand how the state works: How the mechanics of public institutions collide with civil society and media to influence opinion or action.

I’ve met families who lost their children due to negligence at public hospitals, covered victims of sexual violence, met those who have unknowingly been part of clinical trials, those who lost family members to extra-legal state violence, those waiting on government aid for disease… and I’ll stop here because this need not be a litany of tragedy.

I’ve seen the frustration and sadness, of both civil society organisations and journalists — both well-meaning — who feel quite sad, that often the work they do to highlight disease or death, goes unnoticed. It doesn’t get government attention, it doesn’t prompt society to act. It lacks impact.

And one thing I’ve heard time and again from families, victims, and survivors, is that: “We hope this does not happen with anyone else again.”

Coming from this locus, when I look at the recent controversy about Pandey faking her death and this leading to increased interest in cervical cancer, I realise that she’s achieved two things which many before her have struggled with.

1. She got real attention on an ignored disease and cause of death in India.

2. Her stunt is poised towards action. Given that cervical cancer is preventable, the new interest can actually get people to take the vaccine, thus ensuring that “this does not happen again with anyone else.”

This is what I have in mind when I think about everyone’s angry opinions on Poonam Pandey faking her death to raise awareness of cervical cancer: What ELSE would it have taken for us to have cared?

What should we be really offended by?

Which brings me to the ethics of what Poonam Pandey did. Whether her shock-marketing was right or wrong, I’m going to leave that to college professors teaching the Bachelors in Mass Media course to sprightly 20-year-olds, and generally to people with more virtue than me.

What I do know is wrong? People dying from preventable diseases.

Am I offended by what she did? I’m ambivalent.

Am I offended by societal inaction on preventable deaths? I’m not ambivalent on this. I’m truly offended that we allow this to happen.

To me, at a public health level, what’s more wrong than Poonam Pandey faking her death is this:

1. We don’t have enough awareness or action around the HPV vaccine.

2. The vaccine is priced prohibitively for most people.

3. 70,000 women may die this year from this preventable disease because of lack of information and inaccessibility to screening and the vaccine.

How’s this for a bit of a rap on what the mortality menu-card in India looks like.

India recorded 1.6 lakh suicides in 2021. Young kids die regularly by suicide in Kota, giving in to the pressure of their competitive exams, and yet the last time we cared about suicide was when Bollywood actor Sushant Singh Rajput died by it. We cared about mental health when Deepika Padukone came out about her own.

1.5 lakh people died in road accidents in 2021. Over a ten-year period, 13 lakh people have died in India in road accidents. But the government stressed more stringent car safety only after Cyrus Mistry died in a car crash in 2022.

India accounts for the highest number of TB cases globally, reporting 3.3 lakh deaths in 2022. We started to care after Bachchan came forward to champion the cause. But alas, we remain top of the class on this for years.

Cardiovascular disease accounts for 27% of all deaths, as of 2017. Yet the last time we cared was when Sushmita Sen and Puneet Rajkumar had heart attacks.

India’s mortality rate.

A doctor I interviewed once put it into perspective: the number of preventable deaths in India each day is comparable to the fatalities we would see if multiple plane crashes occurred daily. And yet, while plane crashes make headlines, these daily losses pass by with little fanfare.

This shock-driven awareness holds true even outside of public health. The last time we really cared about sexual violence, to the extent that it even led to changes in the law, was when the levels of brutality in the Nirbhaya case crossed a threshold of acceptability for us. Likewise, we are not offended enough by climate change itself, but we are offended when climate activists throw tomato soup at Van Gogh paintings to raise awareness.

So yeah—it often takes an extreme, unexpected, or emotionally charged event to jolt public opinion and policy out of complacency, especially on issues typically overlooked or normalised.

So is shock-marketing the way?

Whether it’s for a business or a social cause, marketing falls back on what it knows best: exaggeration. To a large extent, we see exaggeration in advertising and marketing as normal and acceptable.

Should it involve deception? Nothing in life should.

And yet, is exaggeration the same thing as deception? Standing in front of heaven’s pearly gates, I’d have to say — yes it is.

If I’m selling face cream that will make skin smoother, but the ads have been photoshopped to remove pores and blemishes, would you call that exaggeration or deception?

If I overstate how juicy that burger in my burger ad is, when an actual real burger is really quite flaccid and dry, would you call that exaggeration or deception?

That CGI video showing a giant lip gloss at Gateway of India and a Barbie at Burj Khalifa… would you call that exaggeration or deception? You tell me because my dad sent it to me on WhatsApp believing it was a news video. I guess he got punked.

So, if our problem is with exaggeration in marketing, then that chucks all marketers out of the arena, even those who feel like they are ethical today: Why stop at Poonam Pandey? Death to all CGI videos at Gateway of India! (Really, I’d quite like this.)

Whether in marketing, comedy or poetry, there is room for exaggeration, caricature, parody and satire, as long as society can tell the difference between fact and fiction. As long as our critical faculties are alert, alive and sensitive. As long as we behave with rationality and a sense of proportion.

But if that is not where we are — and nothing around me suggests that we are here — then this settles for me that my concerns and ethics lie more with the fact that we no longer are poised to take action. We no longer respond to reason or criticality with education and information. Instead, we need to be jerked out of our irrationality and apathy by extremeness and shock. The more the gore, the more we will titter, maybe even act.

My comment is not on Pandey and stunts like this which may come in future. It is on us: Are we the ones who make and justify the case for shock-marketing in public health?

Check in with me in a few weeks on whether I got the HPV vaccine myself or not.

Remind your friends to get jabbed 💉