Dopamine Decoded: The Chemical We Blame But Don’t Understand

The most trustworthy source of food and

fitness journalism in the country.

Editor’s note: Hi there. Today’s piece is a deep-dive on dopamine, co-authored by me, Samarth Bansal, and Ankush Datar, our regular contributor.

Between the two of us, we reviewed multiple articles, papers and books and what you will read is a synthesis of what we’ve learned into these seven points about this widely misunderstood chemical.

PS: Here is a short feedback form to help us understand how we’re doing. From day one, TBT has been published in service of our readers—and I want to ensure we’re on the right track. Would you please share your thoughts? Link here. Thank you!

– Samarth (samarth@thewholetruthfoods.com)

You’ve probably heard about dopamine. Or at least about the “dopamine hit”—a phrase that’s everywhere these days, tossed around to explain why we doomscroll, binge content, or impulse-buy online. It’s often called the “pleasure chemical,” something that supposedly makes us instantly happier.

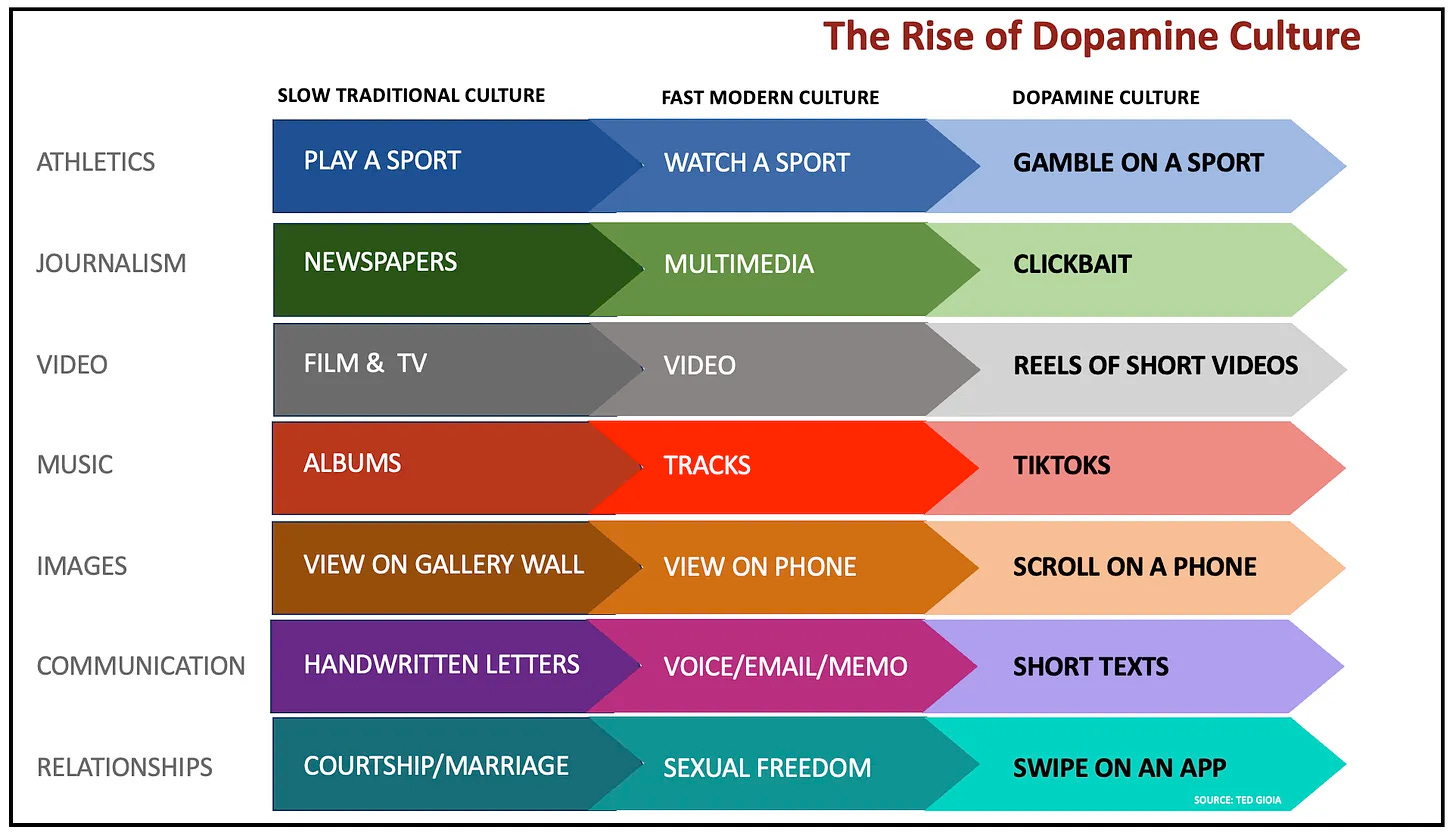

Ted Gioia’s viral article (strongly recommended) included an excellent chart (below) showing how dopamine-driven activities have increasingly dominated our leisure time. It puts so much of what we see around us in perspective.

Over the last few years, this neurotransmitter—a chemical messenger used by neurons to communicate—somehow became a symptom of what seems off with modern life: why things feel shallow, why our attention feels scattered, and why we ourselves often feel unsatisfied despite constant stimulation.

Yet, how exactly dopamine works is misunderstood in popular media. That’s partly because scientific understanding is still evolving, but even the mechanics where there is enough consensus get lost.

In this piece, we have put together seven points to help you make sense of dopamine—the defining chemical of our times.

One: Dopamine isn’t just pleasure. It’s motion, motivation and more.

That popular notion of dopamine as the “pleasure chemical”?

It’s narrow and misleading. Dopamine’s role in our brain is vastly more complex: it orchestrates voluntary movement, modulates attention, facilitates learning, and reinforces behaviours that help us survive and thrive.

Consider two critical aspects.

First, dopamine is crucial for movement. When dopamine-producing neurons degenerate, as happens in Parkinson’s disease, people struggle with even the most basic motions like walking or reaching for objects—revealing how fundamental this chemical is to our physical functioning.

Second, while dopamine is central to the brain’s reward system, it is not the sole cause of pleasure. The warm glow of satisfaction comes from a system of neurochemicals—endogenous opioids, endocannabinoids, serotonin, and others all play their parts.

Two: Dopamine evolved for survival—not self-sabotage.

Dopamine is not a mistake of evolution. It’s a feature, not a bug.

In ancestral environments, finding food, shelter, social allies, and mating opportunities required active pursuit. Dopamine made the hunt worthwhile. It rewarded exploration, curiosity, effort, and delayed gratification—traits that increased chances of survival and reproduction.

In short, it evolved as a motivational tool that pushed our ancestors to take necessary risks, learn valuable skills, and persist through challenges. Not to make us miserable or addicted.

So the “problem” isn’t dopamine itself, but rather how our ancient neurochemistry now operates in an environment radically different from the one it was calibrated for—a world where rewards that once required substantial effort now arrive with unprecedented ease and frequency. (More on this in point seven.)

Three: Dopamine peaks before the reward. Not after.

One of the most important things to understand about dopamine is that it spikes in anticipation of the reward, not during or after. (Read this paper for details.)

Think about it: The feeling before that sip of coffee. The feeling right before that Instagram swipe. The feeling before eating that delicious dessert. The feeling before lighting that cigarette.

That buzz of anticipation—that’s dopamine at work. It’s not the reward itself that triggers the strongest dopamine response; it’s the moment just before.

This explains why pursuing something often feels more exciting than actually getting it. The chase, the anticipation, the feeling that something good is just within reach. That’s when dopamine levels peak. Our brains are wired to get more excited about what might happen than what’s actually happening.

This anticipatory spike is why we keep checking our phones, refreshing our email, or returning to social media—the possibility of reward keeps our dopamine system engaged and motivated, even when the actual rewards often disappoint (next point).

We strongly recommend you watch this five minute video from Robert Sapolsky.

Four: Dopamine doesn’t care if you “like” the reward. It just makes you “want”.

Dopamine doesn’t make value judgments. It doesn’t evaluate whether what you’re chasing is good for you. It simply amplifies wanting.

That’s why you can crave things that hurt you—compulsively scrolling social media feeds, gambling away savings, or chasing toxic relationships—even when you know they leave you worse off. Dopamine is a powerful wanting engine, not a happiness guarantee.

So when you find yourself checking notifications before you’re even fully awake, it’s not because you genuinely love what those notifications contain. It’s because your brain is just…seeking.

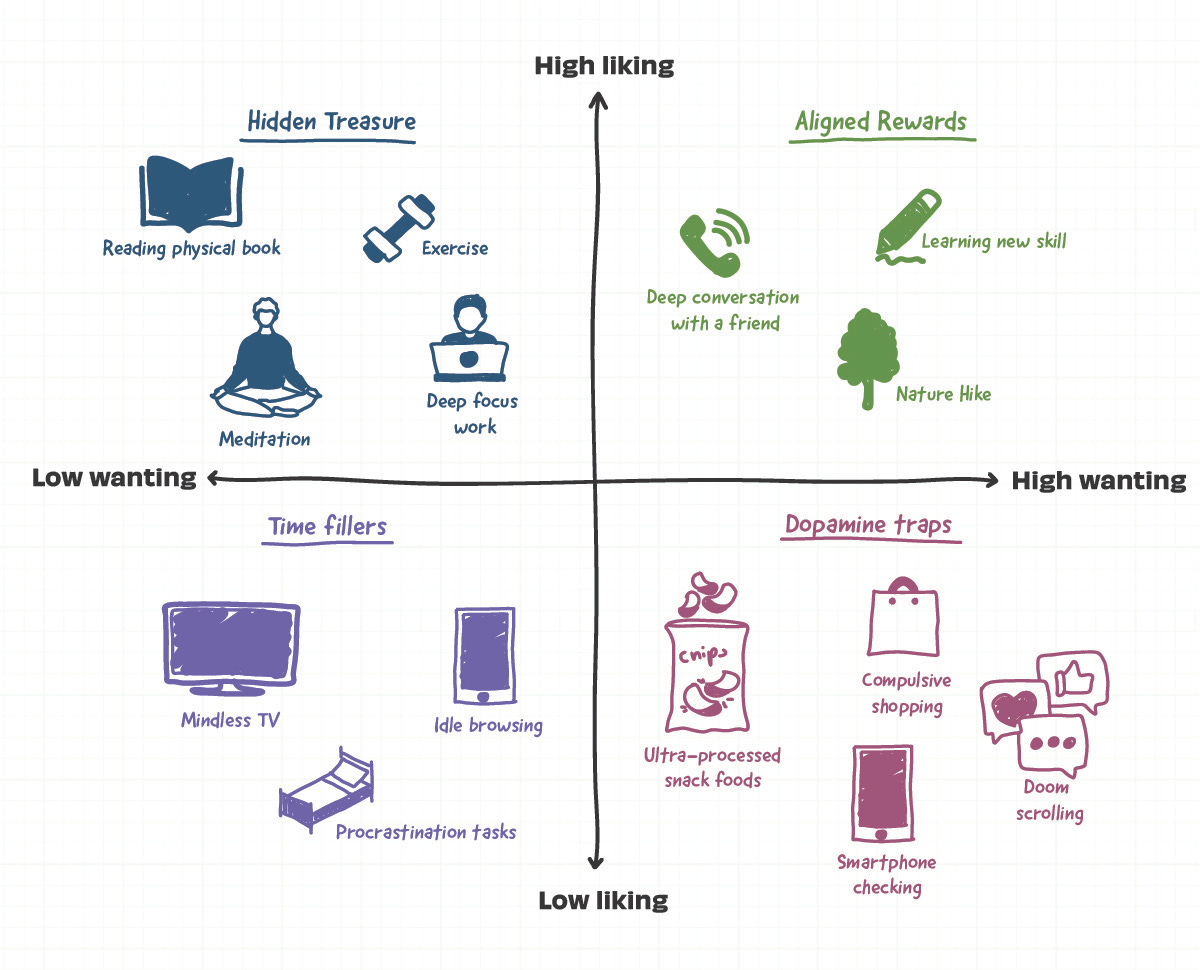

This is the critical distinction neuroscientists make between “wanting” and “liking” systems in the brain—you can want something intensely (high dopamine) but not enjoy it much when you get it. The wanting persists, even when the liking disappears.

Five: Uncertainty triggers the strongest dopamine surges.

The brain releases much more dopamine when rewards are unpredictable. When you can’t quite predict if or when a good outcome will happen, your brain becomes obsessed with checking, chasing, and hoping.

This principle—called “variable reward scheduling”—makes experiences far more addictive than consistent rewards.

Why does uncertainty create such a powerful effect? It all comes down to something neuroscientists call “reward prediction error”—the gap between what you expect and what you actually receive.

When a reward is completely predictable, there’s no error and thus a smaller dopamine response. But when rewards come unpredictably, your brain experiences constant prediction errors that trigger powerful dopamine surges.

Consider these everyday examples.

Slot machines don’t pay out on a set schedule—they pay randomly. That’s why gamblers get hooked despite knowing the odds favour the house. Each pull creates that “maybe this time” anticipation that floods the brain with dopamine.

Social media platforms have mastered this same principle. Notifications arrive unpredictably, likes appear at random intervals, and feeds constantly refresh with potentially rewarding content.

Dating apps like Hinge, Tinder, and Bumble have perfected this neurochemical hook. You never know when you’ll get a new match, when someone will respond to your message, or when that person you’re interested in will finally like you back. Each time you open the app, there’s that moment of anticipation— “will this be the time?” —creating the perfect conditions for a dopamine surge regardless of the outcome.

This isn’t accidental. App designers understand that uncertainty maximises engagement. It’s not necessarily making your overall dopamine levels abnormal, but rather specifically reinforcing the checking and scrolling behaviours through precisely engineered reward timing.

The more unpredictable the reward, the stronger the dopamine response—and the more difficult it becomes to break the cycle.

Six: Dopamine is not the only player. It’s part of a system.

While dopamine gets most of the attention, it’s not working alone. Our brain relies on multiple neurotransmitters working together, not just one chemical driving everything.

Feelings like deep contentment, connection, and peace often involve other neurotransmitters — serotonin, oxytocin, and endorphins. Dopamine drives seeking and excitement, but it doesn’t deliver lasting satisfaction or emotional security on its own.

You feel a short dopamine buzz when someone likes your post, but the warmth you feel after a deep conversation with a friend comes largely from oxytocin. The lasting fulfillment after finishing a challenging project depends more on serotonin than dopamine.

This is why trends like “dopamine fasting” miss the mark. As explained in a Vox article on these Silicon Valley practices, your brain isn’t simply a gas tank of dopamine that can be depleted or refilled at will. The idea that your dopamine levels are either “too high” or “too low” is, according to neuroscientists, essentially meaningless. Our brain chemistry is far more nuanced than that.

Understanding this fuller picture helps us move beyond simplistic explanations that make dopamine the villain. It’s not dopamine itself that’s the problem—it’s how modern technologies often stimulate only certain reward pathways while neglecting the rich complexity of what makes us truly feel fulfilled.

Seven: The real problem is overstimulation. Not dopamine.

Dopamine is not broken—our environment is. What we face today is an unprecedented mismatch between our ancient neurochemistry and modern technological design.

Our ancestors’ dopamine system evolved in a world of scarcity, where rewards were unpredictable and required effort. Today, we live in a world meticulously engineered to maximise engagement. App notifications, social media feeds, streaming platforms, and even food products aren’t designed around human wellbeing—they’re optimised to keep us engaged, clicking, and consuming.

The average person now receives more potentially dopamine-triggering stimuli in a day than our ancestors might have experienced in months.

Hyper-palatable foods with precisely calibrated sugar-fat-salt ratios. Infinite content streams that adjust to your preferences in real time. One-click shopping that removes all friction between desire and acquisition. These systems don’t just satisfy our existing desires—they actively manufacture wanting.

And so, over time, this chronic overstimulation can subtly shift the brain’s sensitivity to rewards, making simple pleasures feel less exciting.

What we are experiencing isn’t just about willpower or personal choice. We are facing technologies specifically designed by thousands of engineers to bypass our cognitive defenses and target our motivational circuitry directly.

And hence, the solution isn’t vilifying dopamine or pursuing “detoxes.”

It’s recognising the fundamental asymmetry in this relationship: individual humans with limited cognitive resources versus trillion-dollar industries with every incentive to capture our attention.

Which is why understanding dopamine isn’t just trivia—it’s a step toward reclaiming agency in a world designed to exploit our oldest neural pathways.