Rapid Fiver: Is even a little alcohol harmful? And 5 other things to know!

The most trustworthy source of food and

fitness journalism in the country.

Editor’s note : Hello there, this is Samarth Bansal, the Editor of Truth Be Told.

It can be a little hard to make choices that promote health and safety, right?

How to buy the right running shoes? How to buy a safe whey protein supplement? Should you drink alcohol? Can you trust the media stories about health? And what about all the hidden toxic pollutants lurking in your home? How to get rid of them?

Today’s issue deals with these questions. We are back with our curated edition where we share our favourite health writing from outside the TBT universe. Five things. Happy reading!

One: The great alcohol health flip-flop

In the mid-1990s, researchers started suggesting that alcohol is good for health: small amounts can favourably tweak cholesterol levels, keeping arteries clear of gunk and reducing coronary heart disease. Moderate alcohol was endorsed by many doctors and public health officials.

See this front-page New York Times story published on January 3, 1996.

Not anymore.

This is the New York Times in January 2023 — 27 years later!

Umm…so what happened?

Tim Requarth tells this fascinating story in Slate, exploring the historical roots of why alcohol health advice is so divisive. Why was it common knowledge yesterday that alcohol in moderation is good for you, but it’s common knowledge today that no amount of alcohol is OK?

When I first clicked to read this article, I thought it’d be just another story telling me how the industry distorts science: they rig studies, fund research institutions to induce biases, selectively amplify favourable results.

Yes, it talks about all that — because all that happened — but it goes much beyond and captures the nuance of how individuals should think about their alcohol consumption, which is so often missing from these stories. Long and balanced piece. Worth your time.

“My read of the literature is that light drinking (think half a drink a day) might slightly reduce the risk of a heart attack in older adults, but even then, the negative effects on overall health outweigh the benefits. The truth is that as little as one drink a day increases the chances you’ll die sooner, and heavier drinking leads to various other health and behavioral issues—making alcohol the seventh-highest cause of death and disability worldwide. From a public health perspective, reducing per capita alcohol consumption saves lives, full stop.

Alcohol, especially wine, has basked in the warm glow of what industry insiders call a “health halo.” Consumers not only think it’s relatively harmless (which is true at low levels) but also actively beneficial (which is likely false). The updated guidelines simply mark the fading of this radiant aura, rather than signaling a return to Prohibition. “The main message is not that drinking is bad. It’s that drinking isn’t good. Those are two different things,” Hartz said. “Like, cake isn’t good for you. Getting in a car isn’t safe. Life has risks associated with it, and I think drinking is one of them.”

Two: Spot the trickery in science writing

I have been following Stuart Ritchie since I read his outstanding book “Science Fictions: The Epidemic of Fraud, Bias, Negligence and Hype in Science” back in 2020. (At that time, I was trying to make sense of the multitude of scientific studies related to the pandemic.)

The book highlights the significant challenges in contemporary science and provides a thought-provoking critique aimed at improving the scientific method rather than disapproving of it.

In this article, Ritchie offers valuable advice on protecting oneself from problematic science journalism prevalent in mainstream media and social platforms — how to sort the real stories from the conspiracies, fakes and exaggerations. I am sharing three snippets here, though I highly recommend reading the full article if you are an active consumer of health and science writing.

“Science works slowly. Each new study is usually a small brick in a very big wall, adding a little piece to our knowledge on some topic. Genuine breakthroughs – discoveries that revolutionise an area of science – are few and far between.”

“Media headlines always have the potential to overrate scientific studies. But often, hype about science comes not from journalists, but from the scientists themselves.”

“We saw above that constant questioning is necessary. But the point is to follow the evidence, not to pick up any old scraps of argument and throw them at the mainstream consensus. And the point is to question everything – including your own side”

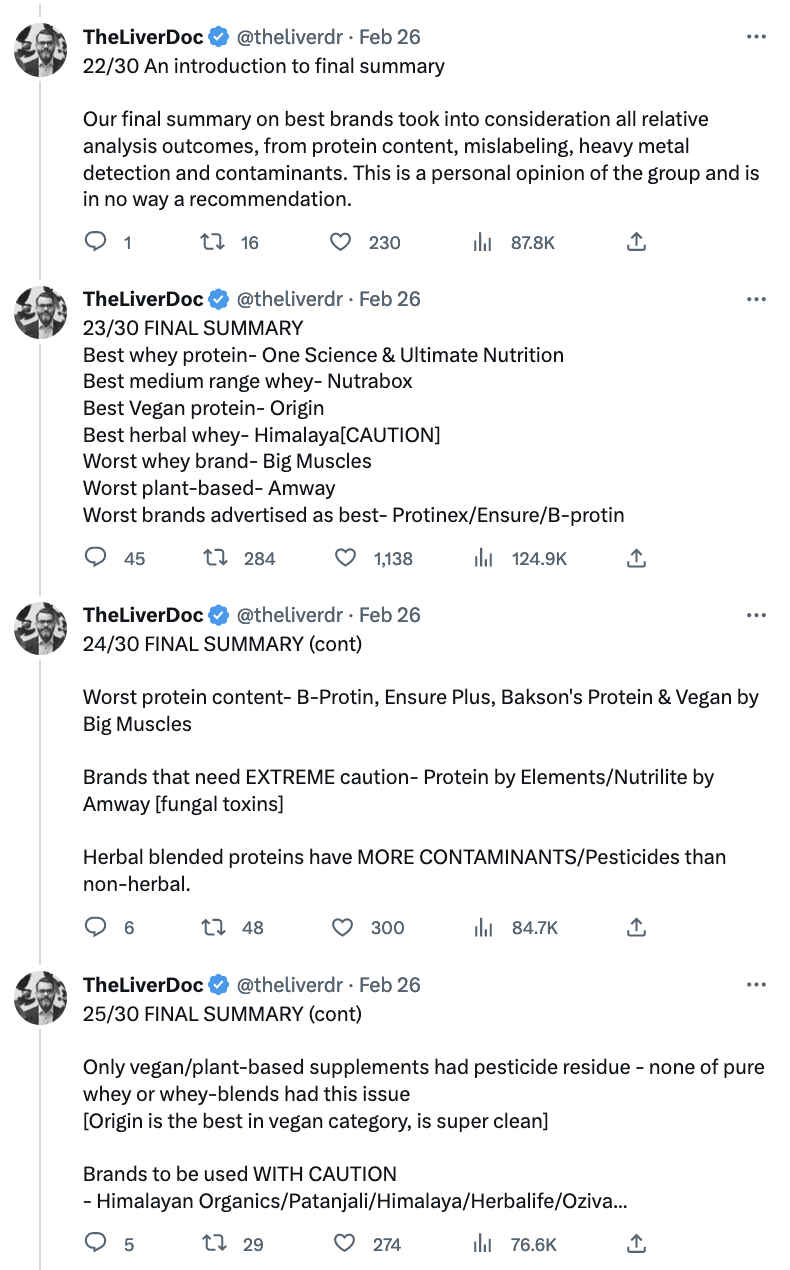

Three: Who’s telling the truth on protein supplements

I have always been curious about the quality of the whey protein supplements I purchase. There are two well-known problems with what’s available in the market: some are contaminated with heavy metals like lead, arsenic, and mercury, and some may not provide the advertised amount of protein as indicated on the label.

Unfortunately, I have never had access to reliable data to inform my decision-making, so I just go with what my friends recommend.

So it was refreshing when I saw the “Protein Project”, a public-health initiative funded by Paras Chopra to conduct comprehensive tests on 36 popular brands in India for protein content, contamination and adulteration. The research was led by Dr. Abby Phillips, a specialist in liver transplant medicine.

You can read Dr Abby’s Twitter thread here, and watch their discussion here. Here is the summary, but I strongly recommend you read the background first.

Important clarification: As a publication, we do not endorse specific brands. Please exercise your own judgement and discretion before making any decisions based on the provided findings.

That being said, I am sharing this information because I genuinely appreciate this initiative, which serves as a remarkable example of “citizen journalism.” In an ideal world, we wouldn’t have to worry about the quality of products, as it would be the responsibility of regulators to conduct thorough evaluations.

However, in the absence of actionable information from the regulator, Paras and Dr. Abby took it upon themselves to do so. After careful consideration, I found no conflicts of interest, which further strengthens my belief that this valuable project deserves a wider audience.

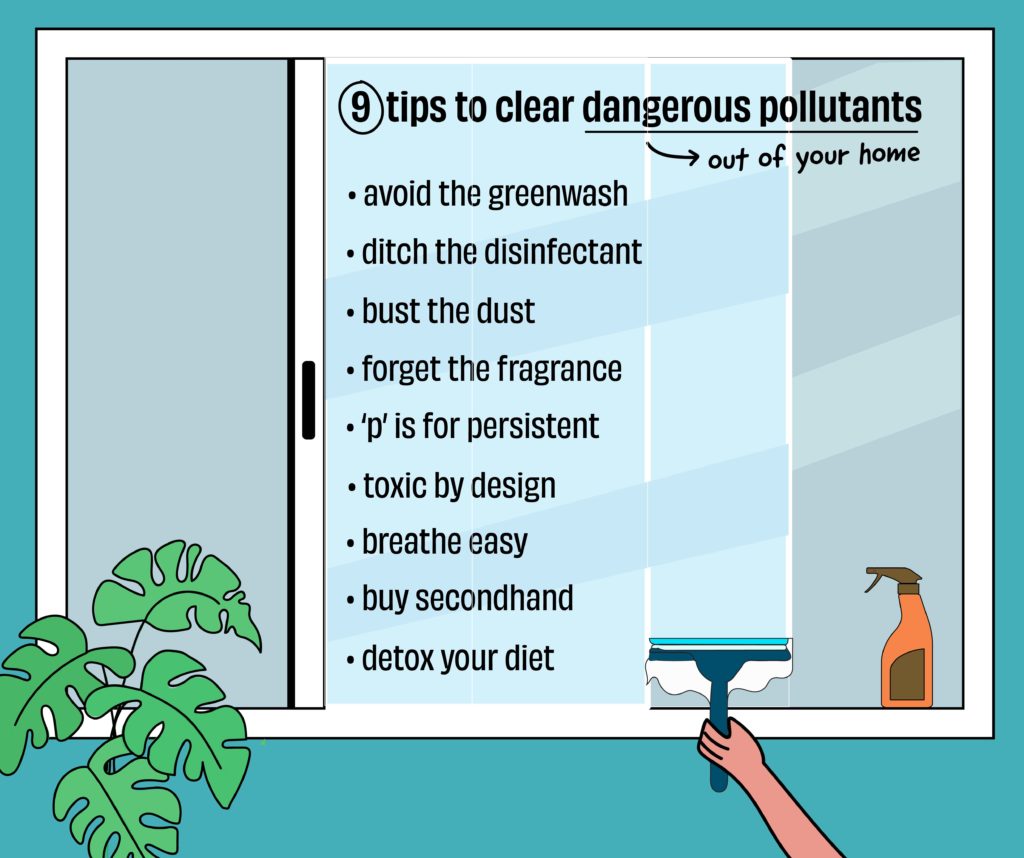

Fourth: How to clear dangerous pollutants out of your home

After discovering banned chemicals and concerning levels of persistent organic pollutants in her blood test, environmental writer Anna Turns embarked on a mission to protect herself and future generations from these legacy pollutants.

All of us are exposed, but we often overlook toxic chemical pollution and how it affects us. So I liked this article in The Guardian, where she distilled the latest research into practical and simple tips.

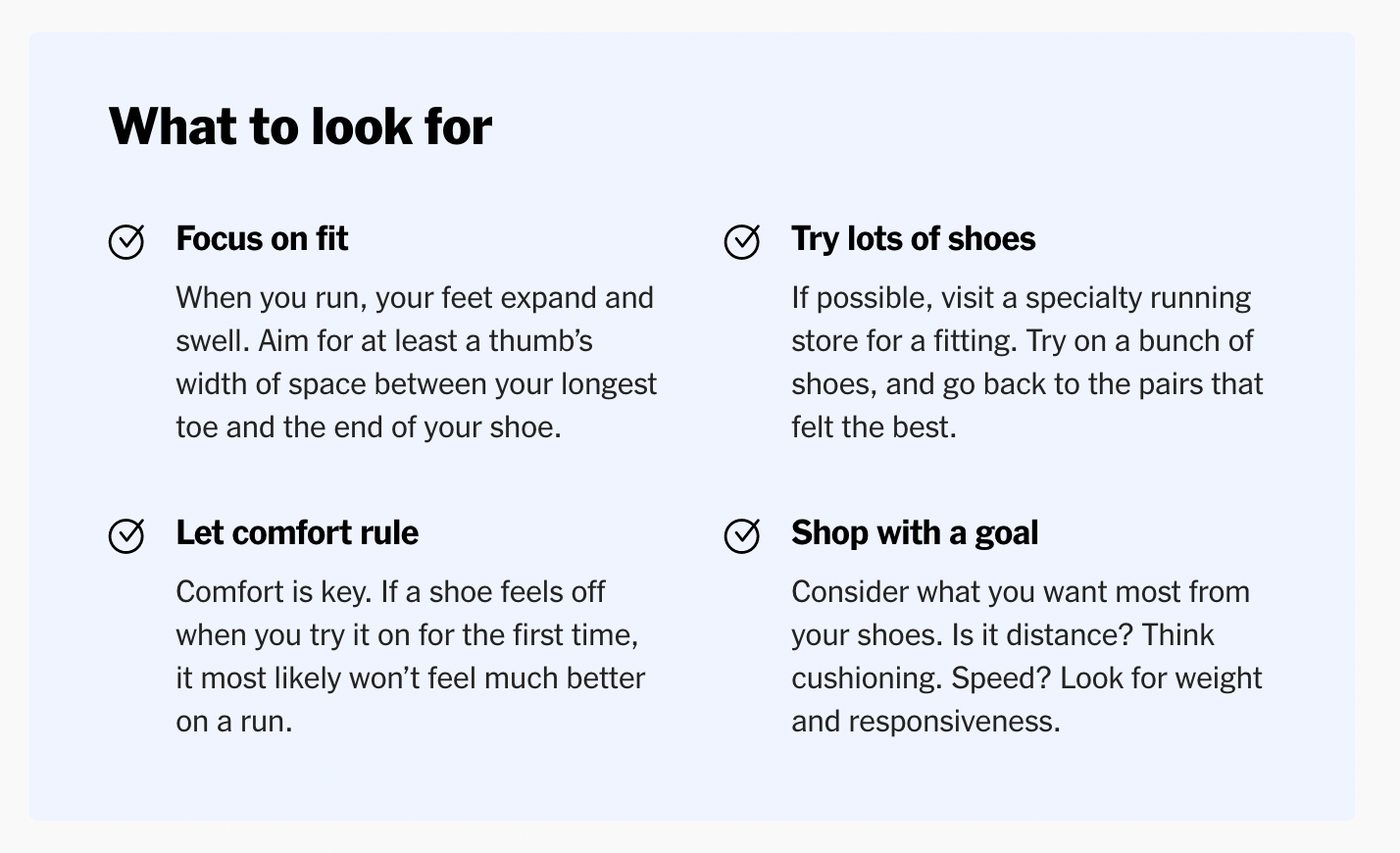

Fifth: How to choose the best running shoes

This guide is an excellent resource. I learned about the different types of shoes, including “neutral” and “stability”, as well as the anatomy of a running shoe and valuable tips for finding the right fit. (I really wish I had read it last month before I bought my new pair of shoes.)

> Good running shoes can make the difference between a run realized and a run refused. And even though there’s some trial and error involved in finding the right pair for your feet and goals, the payoff is real: You’ll have shoes that lay the groundwork for a comfortable, rewarding, and enduring pursuit—whether you’re running primarily for your health or for personal bests.

Bookmark it.

That’s it for today. Hope you found these links useful!