How Food Got Divorced From Flavour

The most trustworthy source of food and

fitness journalism in the country.

Editor’s note: So much of the discourse around the food industry centers on whether packaged food is “good” or “bad” for our health. This assumes that the problem with processed food is a problem with nutrition alone. I have always found this framing off, because while yes, nutrition absolutely does matter, it reduces food to nutrients alone—and ignores how food is also about culture and how we form relationship with the world around us. Food choices aren’t made simply based on what tastes best, but who makes it and how. At least that’s how I think.

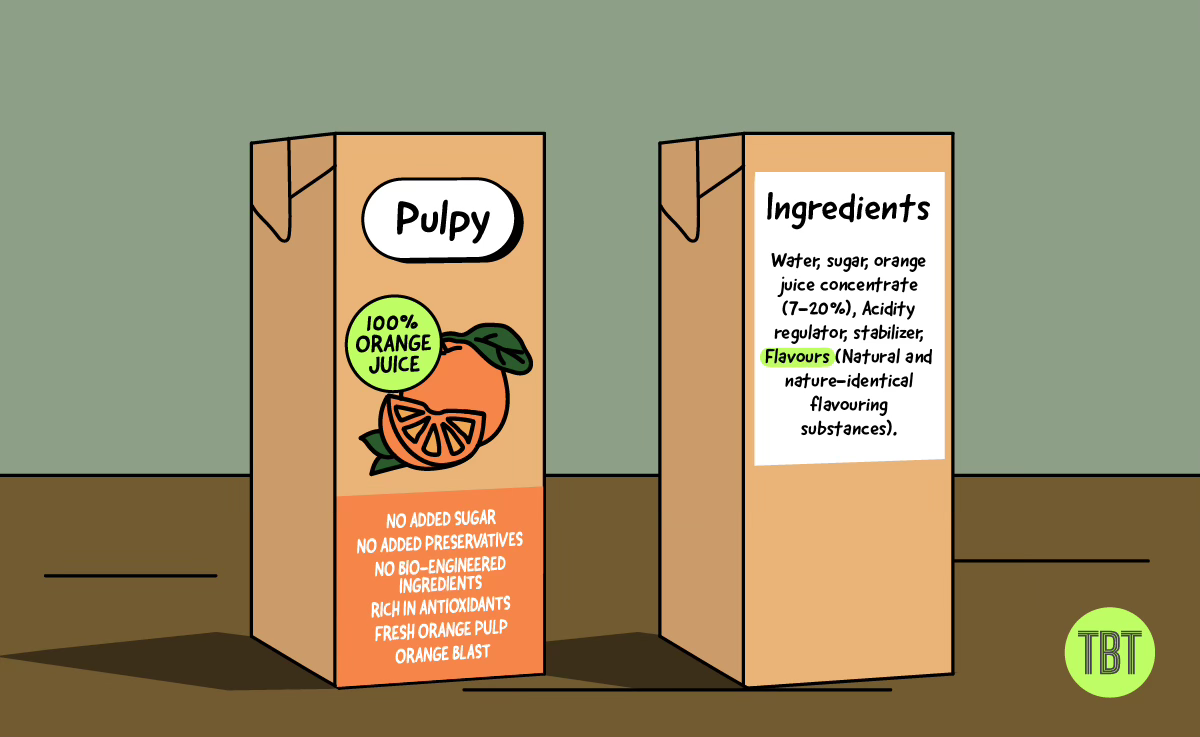

Which is what you will discover in today’s deep dive into the world of flavours from my colleague Anushka Mukherjee. Read to learn how you get orange juice without any orange, why industry adds lab-made strawberry flavour on top of real strawberries, and what to really make of claims like “natural flavours only” on packaging. This piece should clarify so much about what passes as fake-tasting—yet often delicious—products in the market, and why this matters for our food environment.

PS: Here is a short feedback form to help us understand how we’re doing. From day one, TBT has been published in service of our readers—and I want to ensure we’re on the right track. Would you please share your thoughts? Link here. Thank you!

— Samarth Bansal (samarth@thewholetruthfoods.com)

Last year, I read a short, punchy edition of the New York Times’ daily newsletter, The Morning, about Melissa Kirsch’s futile attempts to recreate a takeout Caesar salad she’d eaten countless times during office lunch breaks. No matter what she tried, it never tasted like that simple takeout salad.

She confirms what many of us already know: she couldn’t replicate that salad because its taste was inexorably linked to the experience—sustaining herself with a quick meal amid a hectic workday.

It’s the same reason my homemade bhindi aloo sabzi never tastes like the one my brother and I would hungrily wipe from our plates with rotis after exhausting school days—despite following the exact same recipe.

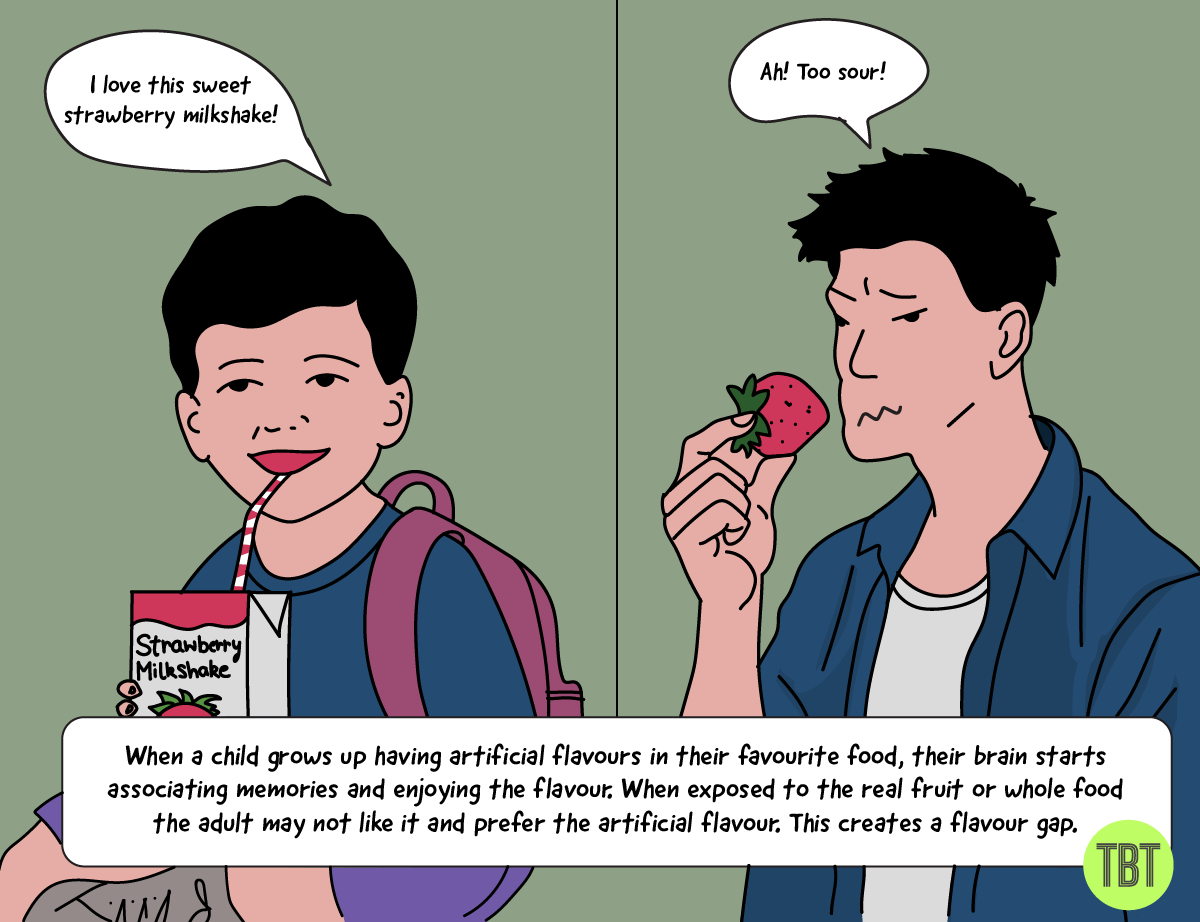

I kept coming back to these subjective experiences of taste as I explored the world of modern packaged food. Growing up, I loved desserts and ice cream with subtle strawberry and vanilla flavours—flavours that now evoke more nostalgia for me than the fruits themselves.

This surprising realisation made me wonder: what exactly is flavour, and why is it so deeply connected to our memories and experiences?

What is flavour? And what is industrial flavour?

Flavour is more than just taste—it’s a complex sensory experience combining taste, smell, texture, and even emotional context. It basically includes any substances, extracts or preparations capable of imparting taste or odour to food.

Think about the juicy sweetness of a mango, the warmth of cinnamon, or the complex richness of chocolate—each has distinctive compounds that our brains register as their unique flavour signatures, often tied to specific moments in our lives.

When cooking at home or in professional kitchens, we extract flavours directly from their source—garlic from cloves, citrus from fresh zest, herbs from leaves. The flavour and its source are one and the same. Flavour comes from food.

But as I discovered, in the world of packaged foods, this connection isn’t always so straightforward: the flavour doesn’t have to come from food.

Follow the incentives. Manufacturers prioritise flavours that are consistent, shelf-stable, and cost-effective. Rather than dealing with the variations of seasonal mangoes or paying premium prices for saffron, the industry prefers standardised solutions. A packaged mango juice or strawberry ice cream needs to taste the same whether you buy it in Mumbai, Delhi, or Bangalore, and must remain unchanged on the shelf for months.