How I went from 102 kg to 74 kg at 50

Surgeries and illnesses didn't stop Sachin Kalbag from getting fit and losing 28 kgs

The most trustworthy source of food and

fitness journalism in the country.

Editor’s Note: How did someone who couldn’t walk 500 meters in 2019 manage to run the Indian Navy Half Marathon in November 2022? How did someone who couldn’t touch his shins find himself doing one-hour yoga sessions three times a week? How did someone in their 40s go from weighing 102 kg to 74 kg, while battling brain surgery, vascular surgery, spondylosis, depression, and Covid along the way?

This is Sachin Kalbag’s remarkable story. With 29 years of experience in journalism, he has held senior editorial positions at newspapers like The Hindu and the Hindustan Times. Now a senior fellow at the Takshashila Institution, he is passionately exploring various policy matters.

Sachin’s story deeply touched me, and I am grateful to him for sharing it with us.

On the evening of November 18, 2022, 36 hours before the Indian Navy Half Marathon was to start, my doctor gave me the news I was dreading. “It’s gout,” he told me. “I am afraid you can’t run the marathon.”

My dream was collapsing. For three straight days, I had intense pain in my toes. After he diagnosed it as gout, the doctor prescribed me Allopurinol tablets, but the pain continued till Saturday evening, and at around 6 pm, 12 hours before the starting gun, I decided to give up.

As I retreated to my bedroom, defeated, something, or someone, kicked me from inside. This moment – the half-marathon – was four years in the making. From 2018 when I was obese at 102 kg, to running 21.1 km, for which I had worked so hard. There was no way I was letting a uric acid swell pull me down. At 8 pm or thereabouts, I threw all caution to the wind, took my night dose, and decided to run. My wife, my rock through my health rollercoaster, said nothing. She only encouraged me.

The race was at 6 am on Sunday. In the company of thousands of other runners, I pressed on. But the pain was unbearable: I ran just 2 km in 18 minutes. With 19 more km to endure, I paused.

It was then that I saw an old Sikh man holding hands with a younger, seemingly fitter man and running. He had to be at least 65 years young, yet he fearlessly charged ahead. It moved me. So I ignored the pain, propelled myself forward, pushing myself harder to surpass him, only to discover a remarkable truth: he was blind! The younger man was his running guide.

That was it.

I started running in utter and absolute pain — but the pain faded into insignificance, no longer holding power over my spirit. I removed my shoes at the 10 km mark to check on my toes. They were black and blue – blood clots had worsened the pain. I did not give up. At every kilometre, I updated my wife. I’d walk 500 metres, then run a kilometre. Three and a half hours after I started the half marathon, I completed it.

I was among the final finishers, but I was not ashamed; I had overcome extreme pain to do something that my friends and relatives would have ridiculed had I declared my ambition to complete a half marathon.

🏃Share this to inspire your friends to push through the odds.

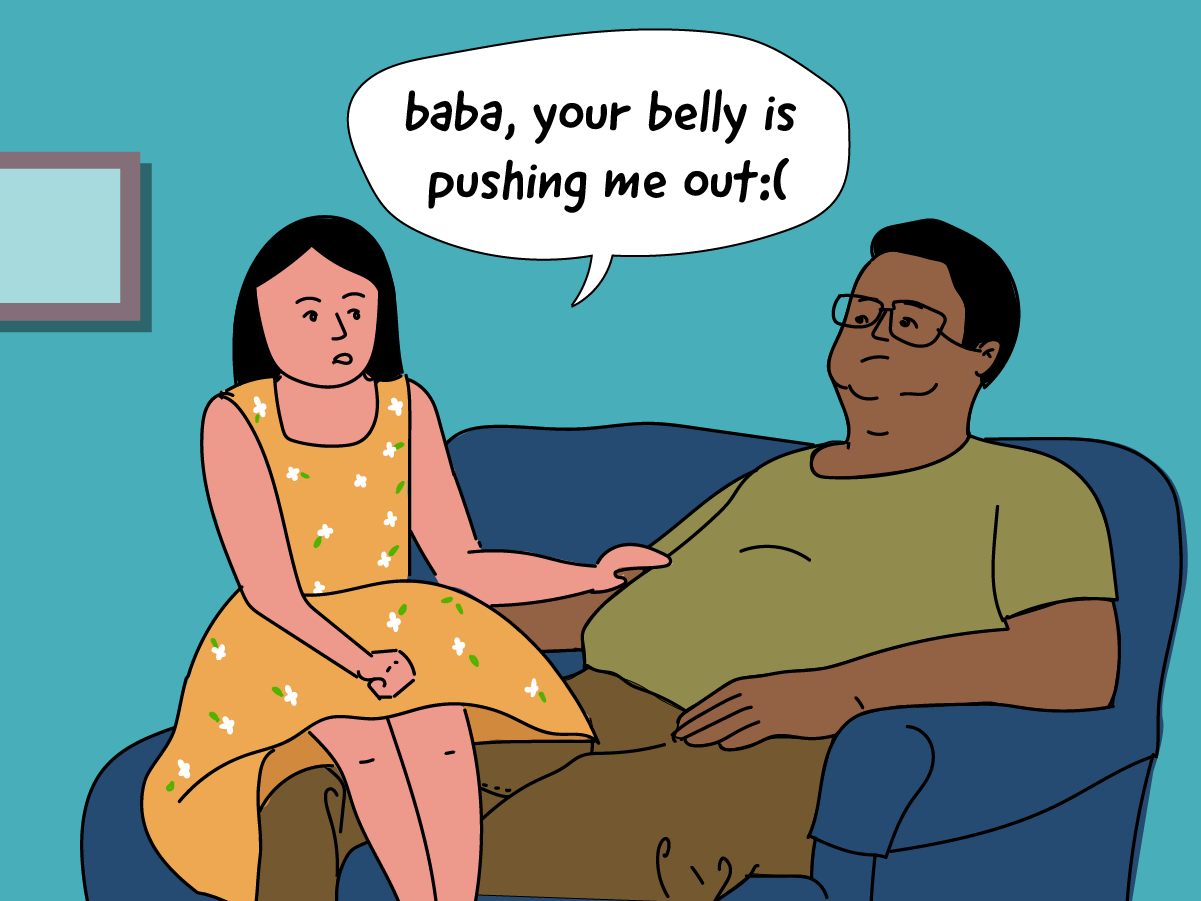

Because four years ago, in 2018, as I was approaching the age of 45, I weighed 102 kg. Sometime that year, as my then nine-year-old daughter innocently settled on my lap to watch television, she exclaimed with heartfelt honesty: “Baba, you are too fat. Your belly is pushing me out.”

That hit hard. She spoke without malice, of course, but the words hit me like a wrecking ball. I was unfit (duh!) and had bloated like a pufferfish.

And at my workplace, despite not slacking off at my duties, many assumed I was lazy — say hello to stereotyping. What they didn’t know was the backstory that dictates why I approach certain tasks at a more deliberate pace.

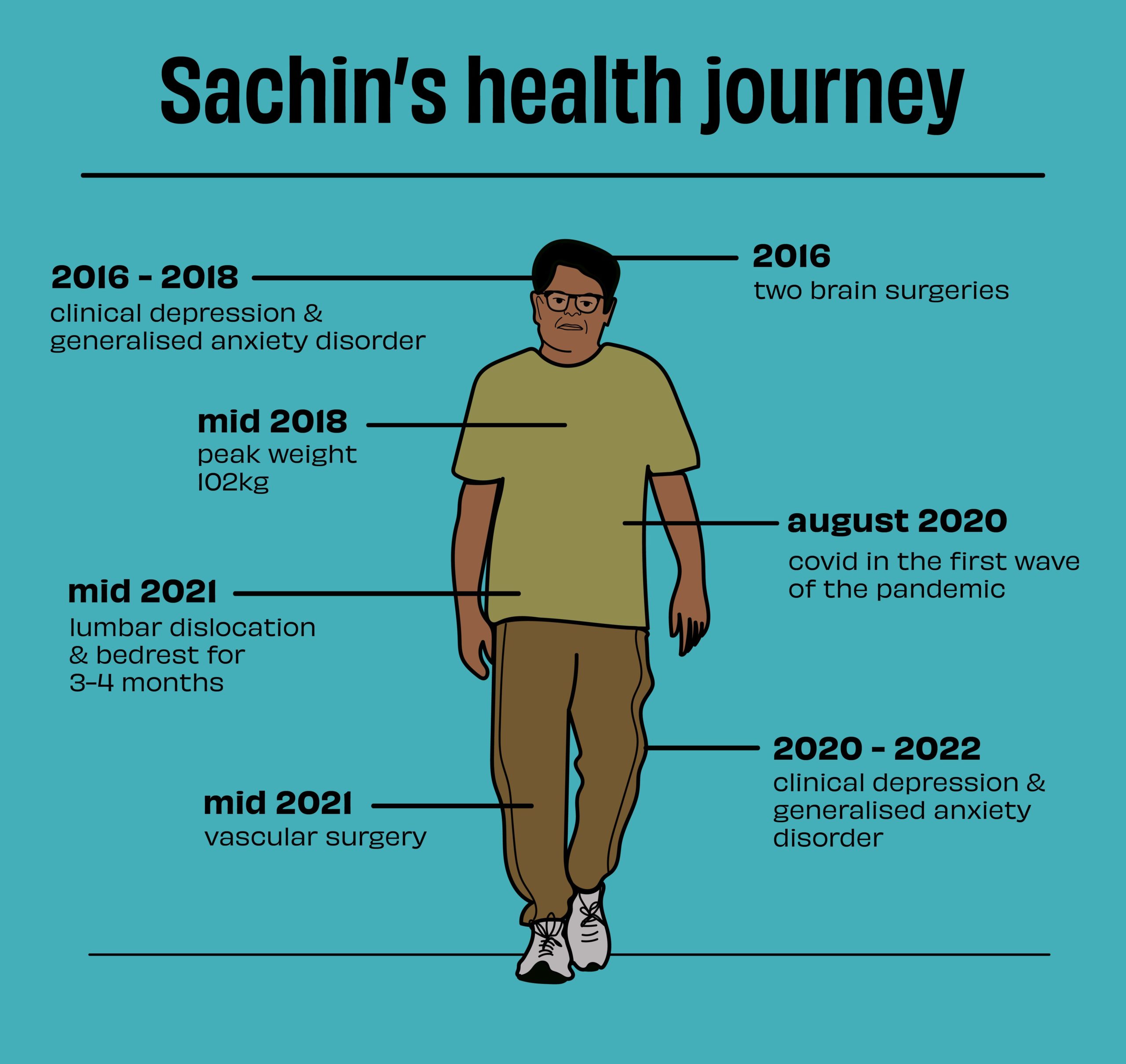

In April 2016, I suffered a double whammy – first, a stroke due to an undetected congenital condition, then mental illness. The stroke left me briefly paralysed. Two complicated surgeries, five days apart, set things right. I miraculously survived and returned to work five weeks later.

My doctor had cautioned me about possible mental health side effects of such a traumatic experience. Prophetic words.

A couple of months later, in July 2016, I was diagnosed with clinical depression and generalised anxiety disorder (GAD). I was suicidal but aware enough to visit a shrink. My excellent psychiatrist put me on medication and therapy, both of which continued for over two years.

Except for my wife and therapist, not a soul knew about my condition: I went to work, suffered through the day, solved my colleagues’ problems, held meetings, brought out a newspaper and returned home, wanting to end it all.

I was force-acting ‘normal’, but it was exhausting, pushing me more towards the edge of the precipice. The dark shadow of clinical depression grows inexplicably: it makes you look older, you take irrational decisions, you cry for no reason, you don’t eat, or you overeat, you don’t have the strength to get out of bed, you lose self-esteem, you feel like being judged all the time, you are scared of everyone and everything — even the phone notifications sets off palpitations.

Many believe that sadness and depression are the same. They are not: sadness is a human emotion; clinical depression is a long-term mental illness.

I began to stress-eat. By December 2016, my weight had climbed to 90 kg. The middle of 2017 witnessed my scale tipping at 99 kg, and before the dawn of 2018, I reached the daunting milestone of a century. I found myself donning XXL shirts and sporting jeans with a 36-inch waist.

Then, there were the jokes. If you are overweight or obese, you are almost always the butt of jokes. Not a single social gathering went by without people offering advice or shooting taunts. Once, I wore what I thought was a smart Fab India kurta with an elegant Nehru jacket when someone asked me why I looked like a scarecrow. I just kept quiet.

Not entirely related to the scarecrow comment, but my self-esteem had hit an all-time low. Professionally, I was doing really well. In late 2015, I quit as the editor of one of India’s most successful tabloids, Mid-Day, which, during my tenure, climbed to No. 7 in the all-India newspaper readership rankings and won several national awards. In November 2015, I helped launch the Mumbai edition of The Hindu as its first Resident Editor. In January 2018, I joined the Hindustan Times as its Executive Editor. As a journalist, I couldn’t ask for more.

Life was seemingly good. My family and friends were celebrating my success, but on the inside, depression and GAD were hurting me almost to the point of killing me. I had no confidence, no motivation, and it took an immense effort just to go to work. That was me — four years before that 21.1 km race. So, yes, whatever you read about depression, it’s not an exaggeration.

But that was then. Between November 2018 and November 2022, a lot happened. Mental illness took its toll – twice – but I had some excellent doctors who treated me on time and with great empathy and sensitivity. My wife was the pillar that held me in place. I also developed — I really don’t know how — extraordinary willpower.

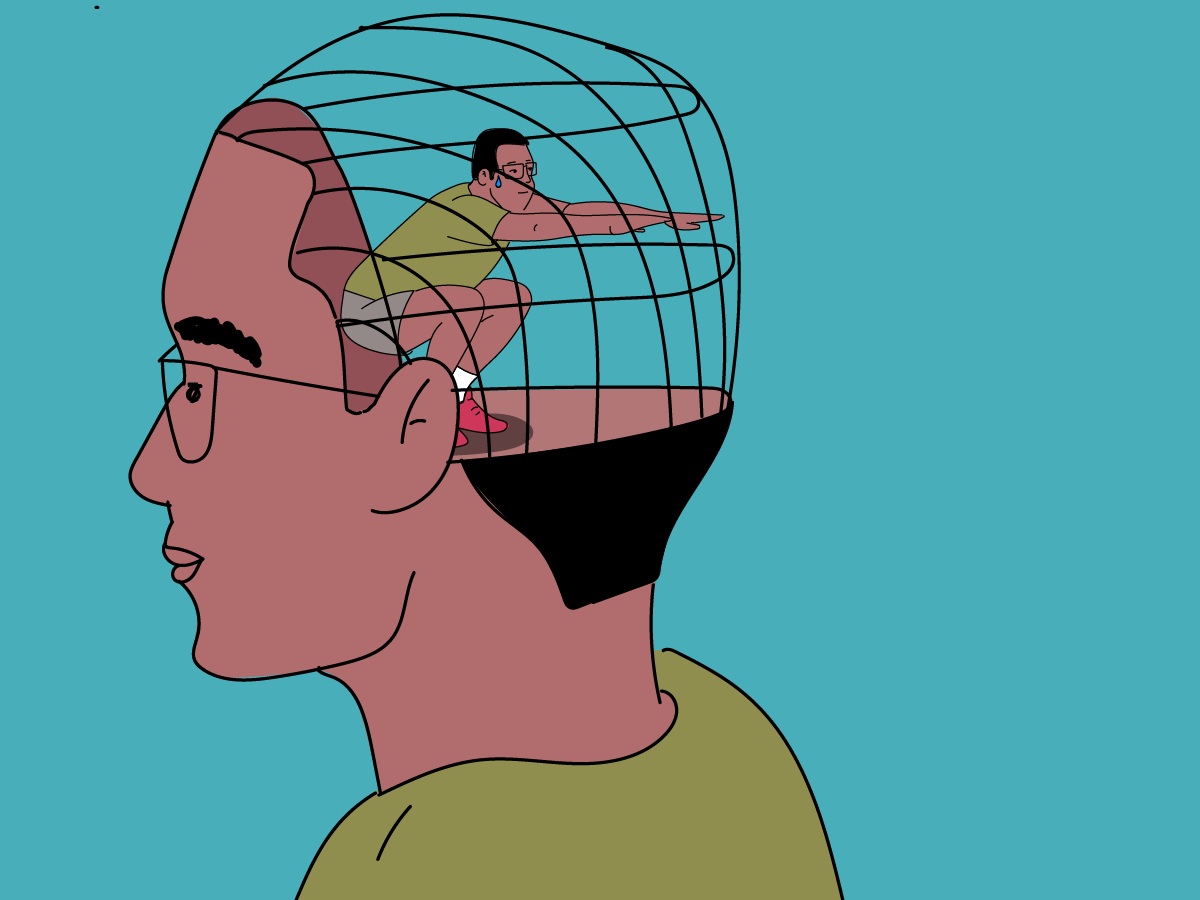

You need immense mental strength to reduce from 102 kg to 74 kg, run an endurance race, and then hit the gym every day. Which is why, perhaps, my fitness journey began just as my depression and GAD phase was ending. Medication and therapy ensured that I recovered to a great degree, but you need an inner voice to push you to get up the next day and work harder.

In those four years, I realised a simple truth: there is no physical fitness without mental fitness. You don’t run a marathon with your legs; you run it with your mental strength. You don’t leg-press 90 kg with your lower limbs; you do it with the space between your two ears.

There is no option but to literally train your mind to not give up.

This is my story. How I got where I am today.

Towards the middle of 2018, as my weight peaked at 102 kg, I had no idea how and where to start exercising. I didn’t want a nutritionist because I did not trust myself to sustain their prescribed food regimen. Besides, their counsel is too expensive. In any case, I had decided that portion control was the way to go rather than depriving myself of the pleasures of food.

I was no different than other overweight people in terms of self-image. Most obese people see themselves in the mirror, imagine being fit and lean at some point, think of the extraordinarily arduous task in front of them, and then give up a few seconds later.

I had done that every single day since I hit 100 kg on the weighing scale: look in the mirror, feel ashamed, go to work, eat more unhealthy food, and then return home to more shame – a living-breathing vicious cycle.

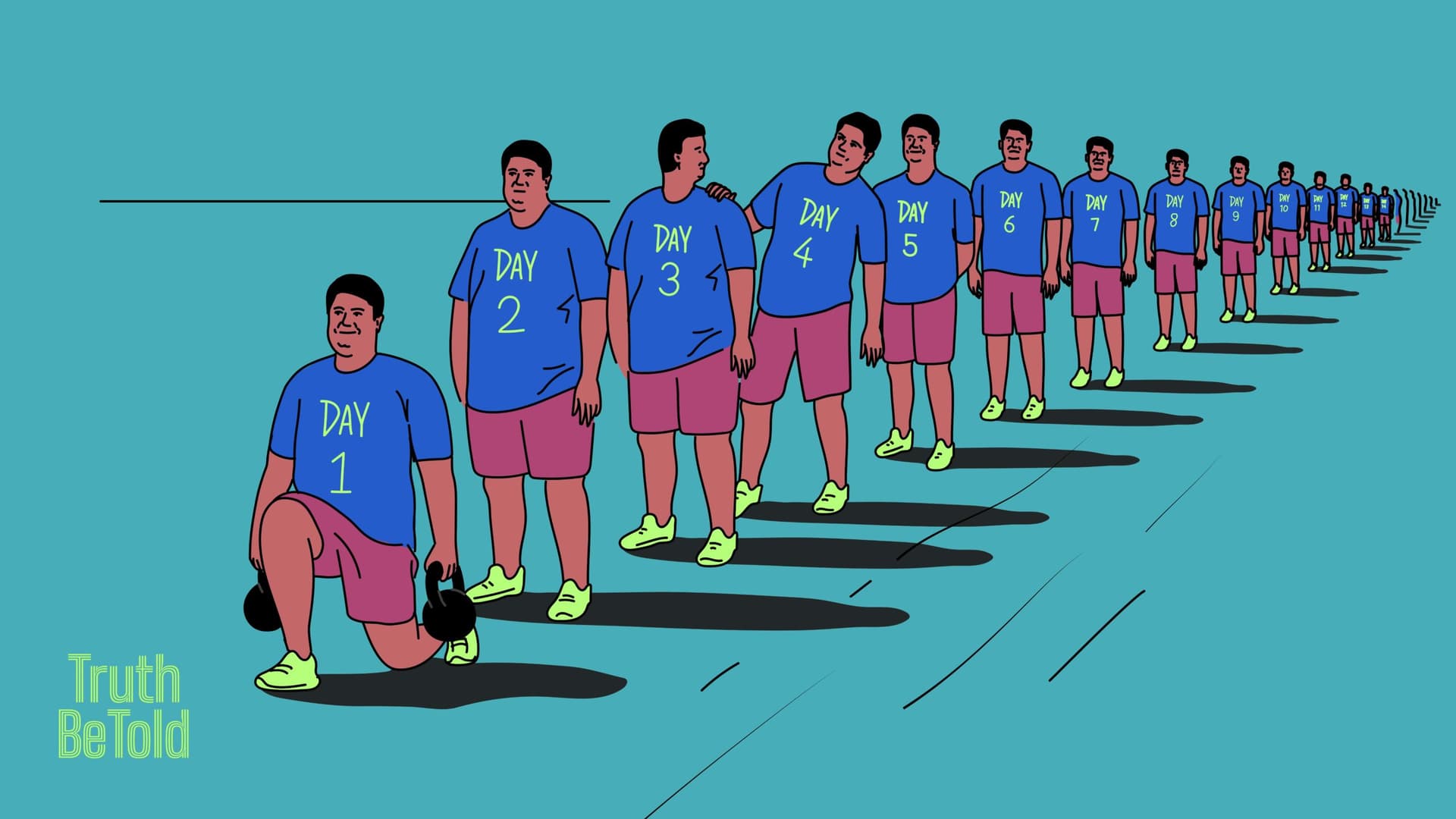

Despite these odds, I started walking at a park near my house. The jogging track‘s circumference is 220 metres. On the first day, I was drained after walking just two laps.

In the past, I had given up after Day One. But my daughter’s words kept coming back to me. I turned up on Day Two. And Day Three. And Day Four. I would walk every day, gradually increasing the distance. By week three, I could walk five rounds – 1100 metres. By December 2018, I walked 3 km every day.

Simultaneously, I started yoga training. My wife, who can easily do challenging yoga asanas, also asked her teacher to coach me. Our yoga guru was clear: “Do not expect overnight results. It will take months and years. Yoga is a process,” she said. “Exercise is not an endgame.”

Those words – “exercise is not an endgame” – stuck with me.

By mid-2019, I could walk up to 8 km daily and do one-hour yoga sessions thrice a week. By the end of 2019, I was walking 10 km a day in 90 minutes, and the yoga lessons continued but with increased intensity. My weight dropped to 87 kg. I was still overweight, but better than the 102 kg earlier.

For me, therefore, small goals worked. I was patient. I did not want to lose 25 kg in 60 days; I was okay with losing it in 18 months or more.

But fitness and weight loss are not a function of exercise alone — diet matters even more. I needed to control my sweet tooth and balance my overall nutrition.

I started with the obvious, simple stuff (it sounds simple, but it is extraordinarily hard, and requires immense discipline and will).

I first reduced my sugar consumption. The more you consume processed sugar, the more you crave it. For over two decades, I had been eating processed sugar in various forms and the body had begun demanding it every day. Cutting it to zero overnight would mean a system shock.

Again, I set my goals small: portion control, rather than elimination, became my guiding principle. Instead of a dessert after every meal, I rationed it first to once every two days, then four days and then a week.

I reduced and then stopped consuming all sugary drinks and no biscuits and cookies at home. At the office, I brought down my vending machine coffee consumption to one cup a day. My wife and I switched to fruit for sugar cravings – apples, grapes, bananas, chikoos.

It took me about four to five months of disciplined rejection of sugar to overcome temptation. It’s hard. If you have a sweet tooth, you’d know.

I felt good, and I was on track.

And then, Covid hit. As Allen Saunders first said in Reader’s Digest in 1957, and then John Lennon immortalised it in song, life happens when you are busy making other plans.

Encourage your friends to not give up, remind them that fitness is a journey🏋

When the pandemic spread, the Hindustan Times, the paper I worked for as its Executive Editor then, began sacking people. In June 2020, my immediate boss was fired, but I survived the purge. The big blow came when nearly 25 of my team members were asked to leave. Many of them were sole breadwinners for their families. As their boss, I was told to call each one and give them the news. I was emotionally drained, and I could not even imagine what my fired colleagues – some friends – went through. My colleagues’ lives were upended in minutes.

On August 30, I contracted Covid, along with my mother. Because of a reduced workforce, I had to work from my quarantine room – recording news videos and podcasts and appearing on six radio shows a day as an analyst, in addition to running two newspaper editions.

No one minded the physical toll it took. As a journalist for 28 years, I worked 12-14 hours a day. What broke us was the mental impact. Everybody, without exception, snapped.

I was no different. The symptoms of clinical depression and GAD were returning — a year and a half after the first phase had ended in December 2018.

My colleagues would share their anxiety over phone calls, and I had to pretend that everything was okay with me while I was in my version of hell: the same fear, the same crying, the same palpitations. I spoke with a psychiatrist whose clinic was close to my office. I was preparing for the long haul. In case the lockdown ended and we returned to work, I needed a counsellor close to my workplace.

As I feared, I was diagnosed with clinical depression and GAD. Just like that, I was on SSRI tablets again, I knew it would be two more years of pain.

Forget exercising. Even getting out of bed during a depressive phase is next to impossible. As days and weeks went by, the SSRI tablets began working, and the first thing I forced myself to do was walk and run. It was like pushing an elephant, but I still don’t know how I managed to do it. I really have no answers.

I was not physically exhausted this time, but mentally, I was out of whack. Yet, I knew I had to do it.

So, I started with my baby steps all over again. Armed with audiobooks and noise-cancelling headphones, I began walking and then running. It took me many weeks to get back to completing my full quota of 10 km a day, which I’d later increase to 15 km. A combination of SSRI tablets and therapy contributed significantly to my recovery.

Just as I was recovering, I sprained my back during a yoga session to prove that I am the embodiment of Murphy’s Law — “anything that can go wrong will go wrong”. I was diagnosed with spondylosis of the L4-L5 vertebrae. The doctor prescribed three months of strict bed rest to avoid surgery.

So the inevitable happened. I put on weight again, and my wife, whose courage knows no bounds, had to bear with a brand-new illness of mine. I could sense that she was tired, too.

I avoided spine surgery (phew!) but was diagnosed with varicose veins and underwent vascular surgery (Murphy’s Law strikes again!).

My fitness story did not have a linear narrative, even though I would have loved to have it thus. Like for thousands of others, there were more roadblocks than I could count: mental illness, temporary physical disability, surgeries, a pandemic that refused to go away, and professional pressure, the equivalent of the earth’s core.

Towards the end of May 2022, when I had had enough, I decided to take a break for a few months, spend time with family and focus on myself; 28 years after I started as a trainee journalist in 1994. I had no job lined up. We went to the United Kingdom to meet some family and friends and made a road trip along the English and Scottish countryside. It was a fantastic holiday.

When we returned, I called my friend Nitin Pai, the director of Takshashila, a Bengaluru-based think tank whose public policy courses are possibly the best in the country. I had graduated from its first public policy cohort in 2012 (with top honours, I hasten to add unashamedly), and I wanted to enrol in their intensive one-year-programme. He offered me a job instead.

Thanks to an accommodating and empathetic work culture at Takshashila, I found myself in a mentally safe space. A combination of this safety, SSRI tablets, and therapy dramatically improved my mental health – to the extent that I gathered the courage and the confidence to complete my first 10 km walkathon in October 2022 and my first half-marathon a month later.

At the risk of repeating myself, mental and physical fitness are connected; we cannot ignore one for the other.

That’s when a friend suggested I join a gym. I was wary of joining one because I was afraid of wasting money and not confident whether I’d be able to meet the intense physical demands. I was wrong on both counts.

In January this year, I started and hired a personal trainer to tone my body, besides losing weight and being fitter for longer. My trainer and I decided upfront that we must focus on consistency, not intensity; your body cannot take the intensity shocks.

He began with basic routines, targeting specific muscle families. In the last six months, I have gone from zero freestyle squats a day to 120, from 10 kg leg presses to 90 kg, from five minutes on the elliptical machine with resistance level one and elevation level five to 20 minutes with resistance level 12 and elevation 16. And these are just three of the scores of exercises that my trainer, a 24-year-old bodybuilder, has designed for my body and age.

But look, the thing is, the battle is half-won by just turning up: unless I have to travel for work or someone is ill at home, I never miss a day at the gym. Remember I mentioned how I had to train myself to not give up on running? That same mental training was now driving my physical training.

It’s been six months, and I know I will not stop. I have maintained my body weight and replaced fat with muscle mass. My yoga sessions and walks (minimum 10,000 steps a day) continue.

🫶 Let your friends know that things will get better

Four years of regular exercise has brought down my body mass index (BMI) from 33 (category: obese) in 2018 to 23.5 (category: healthy weight) in June 2023. My resting heart rate, which was a dangerous 98, is currently 66. In 2018, my shirt size was XXL. I now wear L in certain brands and M in others (whither standardisation?). My jeans size is down to 30 inches around the waist from 36 inches in 2018, and my lowest weight has been 73.9 kg.

The weighing scale does not matter much, though, because my goals have changed. It is about doing more – and targeted – strength and functional training, stretching more in yoga class and walking at least 10,000 steps daily.

I am not unique in my fitness journey, nor is my story even spectacular. Admittedly, though, the last seven years have been tough, and I suspect most of us go through these phases.

I am neither an expert nor the most active guy on the street. I don’t go to the gym to impress women or have any sporting or modelling ambitions (I have a face for radio alone). I exercise for myself. Over the years, I have learnt that weight loss is only a byproduct of exercise — the real purpose of physical exercise is to find yourself and to go beyond self-imposed limitations.

This effort requires an ecosystem, an abstract term that took me four years to understand. To me, it means I have a supportive and trusting partner and a workplace that breathes empathy. It means you operate in a non-aggressive social environment by avoiding toxic people even if they are close to you, and it means you tell yourself constantly that tomorrow, not today, will be the last day of your exercise. Because, you know, that tomorrow never comes.

PS: It takes a village. I would not have been able to do this if I did not have the unending support of my wife, Prajakta Samant, my doctors – Mahesh Chaudhari (neurosurgeon), Vibhor Pardasani (neuro physician), Rohan Habbu (orthopaedic surgeon), Mihir Bapat (spine surgeon), Rajendra Barve (psychiatrist), Milan Balakrishnan (psychiatrist), Mihir Raut (endocrinologist), Avanish Arora (vascular/urology surgeon), Shilpa Deshingkar (yoga teacher), Rishikesh Desai (physical trainer), and my daughters Aanya (human) and Daisy (canine).

Know someone who needs a push? Share Sachin’s inspiring journey📩