How The World Got High On Sugar

The most trustworthy source of food and

fitness journalism in the country.

Editor’s note: The personally fun part of running a publication is publishing stories that speak to my curiosities. The professional responsibility? Making sure those curiosities don’t get so esoteric they alienate readers. Stories for TBT emerge where my instinct says these two meet.

I find the history of food fascinating—and honestly, knowing how we got where we are is a great way to understand what’s working and what isn’t in our modern food ecosystem, especially its impact on our health and everyday lives.

Read today’s story in that context. Anushka Mukherjee—who works as a researcher with me at The Whole Truth Foods—narrates the history of sugar: how it went from a rare crystal in India to shaping our world, our health, and our cravings.

— Samarth Bansal (samarth@thewholetruthfoods.com)

I am not a big sweets-person, but I do experience a phenomenon that all of us are very familiar with: if I have a little bit of a dessert, I immediately want another bite. It’s just too hard to resist (if it’s important to the plot, yes, I am Bengali).

Imagine a rich, dense, decadent chocolate cake, which begins on the inside with a light sponge coated in cream and ends on the outside with a glossy ganache. The first slice is so painfully delightful, and it’s usually when I’m contemplating a second slice that I lament: how can something so good be so bad for me? It just seems unfair. Something about this isn’t correct.

If you’ve had a similar hunch, you’re actually quite right. Sugar in itself isn’t bad for you. Our bodies need it for energy, and we evolved to seek out sweet foods like fruits.

But the sugar you crave? The saccharine, concentrated sweetness of a chocolate cake? They’re fundamentally different from what our ancestors encountered. These concentrated sugars deliver an intensity of sweetness our bodies weren’t adapted to handle.

And it all happened kind of…accidentally.

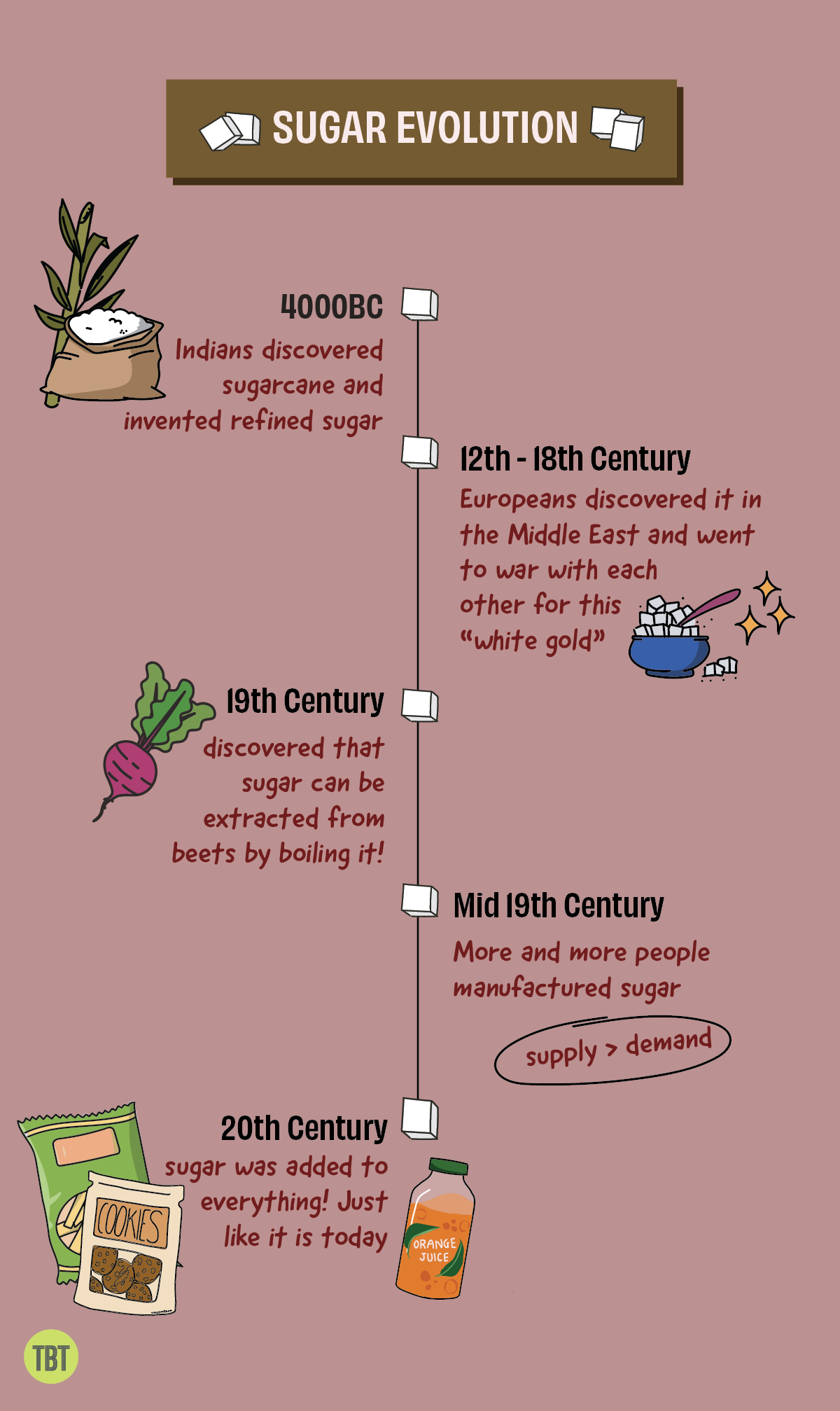

This is sugar’s nearly 6000-year-long journey to reach where it is today. For almost all of that time—about 5700 years—sugar remained in India, where it was locally domesticated, processed and eaten with food and drinks.

Then sugar leaves home, and everything changes: kingdoms fight over it, a blockade leads to a surprise, and we end up with so much sugar we had to figure out what to do with it all.

This is a story of starvation, sugar statues, unsafe water, beetroots, and… Napoleon. All of it comes together to explain how sugar became sugar.

I. India’s sweet start

Sweetness is so native to India that the words sugar and candy both come from Sanskrit—sarkara and khand, respectively. Largely, they mean the same thing: broken pieces or grit.

Over 6000 years ago—around 4000 BC—our ancestors discovered that boiled sugarcane juice, when cooled, becomes rock-hard. Breaking it into small gravelly pieces gave them a sweetness like no other, with a remarkable bonus: it could be easily stirred and dissolved into liquids and foods.

This is when Indians domesticated sugarcane and invented what we now know as refined sugar.

For the next 5000 years, sugar remained largely within India’s borders. When the rest of the world finally discovered it in the 9th century AD, it was the Middle Eastern regions that first got a taste. Arab countries took an interest and improved the process, becoming a major hub for refined sugar until the 14th century.

The scale of India’s head start is striking: even in the 18th century, when European powers were waging wars over sugar plantations and shipping this “white gold” back home, India still consumed more than anyone else—over 7 kilograms per person annually, more than triple Britain’s consumption.

Don’t mistake this for a world without sweetness, though. Humans have always loved sweet things, finding them in honey, fruits, fruit juices, palm and maple syrups, even sweet flowers. In the Middle East, despite having access to sugar, many preferred grapes and honey—they were simply much cheaper.

Because sugar?

Sugar was expensive. Sugar was labor-intensive. Sugar was a rare luxury.

This was especially true when Europe discovered it in the 12th century. They called it “sweet salt” when they first brought it back from the Middle East. And once they got a taste, they were hooked.

Naturally, it became the ultimate status symbol. Royal and aristocratic families commissioned confectioners to create large, elaborate sugar statues for their lavish banquets. The bigger and more beautiful the statue, the higher the family’s perceived status.

In fact, sugar became so exclusive to the wealthy that tooth decay and cavities grew more common in affluent circles—the population even called them “royal afflictions”!

For the average European, though, sugar remained scarce: just a teaspoon per person per year. Centuries passed this way.

All of this would change.

II. Sugar goes global

The first big shift comes with Columbus, who brought sugarcane to what Europeans called the “New World” – the Caribbean colonies. The humid regions of Jamaica, Puerto Rico, Brazil, and Peru presented the perfect conditions for harvesting sugar. The Spanish became the first ones to bring slave labour to their colonized lands to set up sugar plantations—remember, processing sugar was really backbreaking work: the planting, extracting, boiling, pressing. So, one by one, all the major European players shipped over slave labour, mainly from Africa, to their colonies.

For centuries after, it seemed sugarcane fought against being refined, but we found ways anyway. When processing proved too difficult, we invented the three-cylinder mill to revolutionise crushing. When boiling needed more fuel than we had, we cut down entire American forests for woodchips. European countries scrambled in a mad fervour to capture each other’s plantation-rich colonies (the English eventually beat the Dutch, Spanish, and Portuguese to this race)

Sugar had crystallised into a tradeable commodity, driving up commerce in other goods and people. Back in England, where people drank beer rather than unsafe water, sugar made tea and coffee palatable alternatives. As tea and coffee prices soared, sugar found its way into French and German recipe books and bakeries. The demand kept rising, and so did the supply.

Europe had fallen for sugar. There was no going back.

III. The beet breakthrough

The second shift in sugar’s story happened in 1800, after the French Revolution. And this one changed everything.

Until then, the pattern was simple: European powers produced sugar in their colonies, shipped it back home, and traded among themselves. Britain had emerged dominant—the rest of the continent imported much of their sugar (along with tea, coffee, and cocoa) from England. Business as usual.

Then Napoleon, in his quest to dominate Europe, waged war on England. In 1806, he imposed the Continental System, blocking all British imports to Europe.

What did this have to do with sugar?

Well, this blockade led to the discovery of an entirely new kind of sugar, one that could be grown right in Europe’s backyard. And the consequences would be massive.

The story of what happened next is delightfully unexpected: at this point, England controlled about 80% of Europe’s sugar supply—a comfortable monopoly. While the blockade hurt England’s economy, imagine the continent’s predicament: suddenly, no sugar for tea or cakes. But Napoleon wouldn’t budge on British imports. Instead, he launched a feverish race to find sugar, especially in France.

Scientists scrambled to find alternatives. They experimented with everything—vegetables, fruits, even potatoes and mushrooms. After all, sugar is just a chemical—sucrose. You just have to find a new source to extract it from.

Then, at the turn of the nineteenth century, breakthrough: sugar could be extracted from beets through boiling. A German chemist, Franz Karl Achard, perfected the process and lo and behold: a new type of sugar that could be grown right in Europe!

Napoleon rushed his French scientists into action, eager for France to lead this beet-sugar revolution. The continent quickly followed suit—by 1812, beet sugar factories were operating across Europe. With generous government subsidies (Europe was determined to compete with Britain), the industry flourished.

And the legacy remains: even today, 60% of the sugar consumed in Europe comes from beets.

But why was this so significant?

Sugar-making methods now spread from Europe across the globe. Sugar had become easy to produce, profitable, and crucial for maintaining global power. Beets introduced a whole new competing crop – leading to huge surges in beet and cane sugar production.

As more manufacturers jumped in, we faced a new problem: We had more sugar than we knew what to do with.

IV. The industrial rise

And that brings us to the third shift: where there is a supply, demand must be created, right?

To begin with, sugar was added to the war rations for soldiers. Military leaders across the U.S., Europe, and Japan added sugar to soldiers’ rations to increase their endurance. From there, it’s a straight line to the chocolate bars and Coca-Cola that traveled with U.S. troops liberating Europe from the Nazi regime.

During World War II, sugar products like candy were rationed for civilians. Life Savers, a candy brand, even explained to customers why they couldn’t find their candy in supermarkets—their soldiers needed it more.

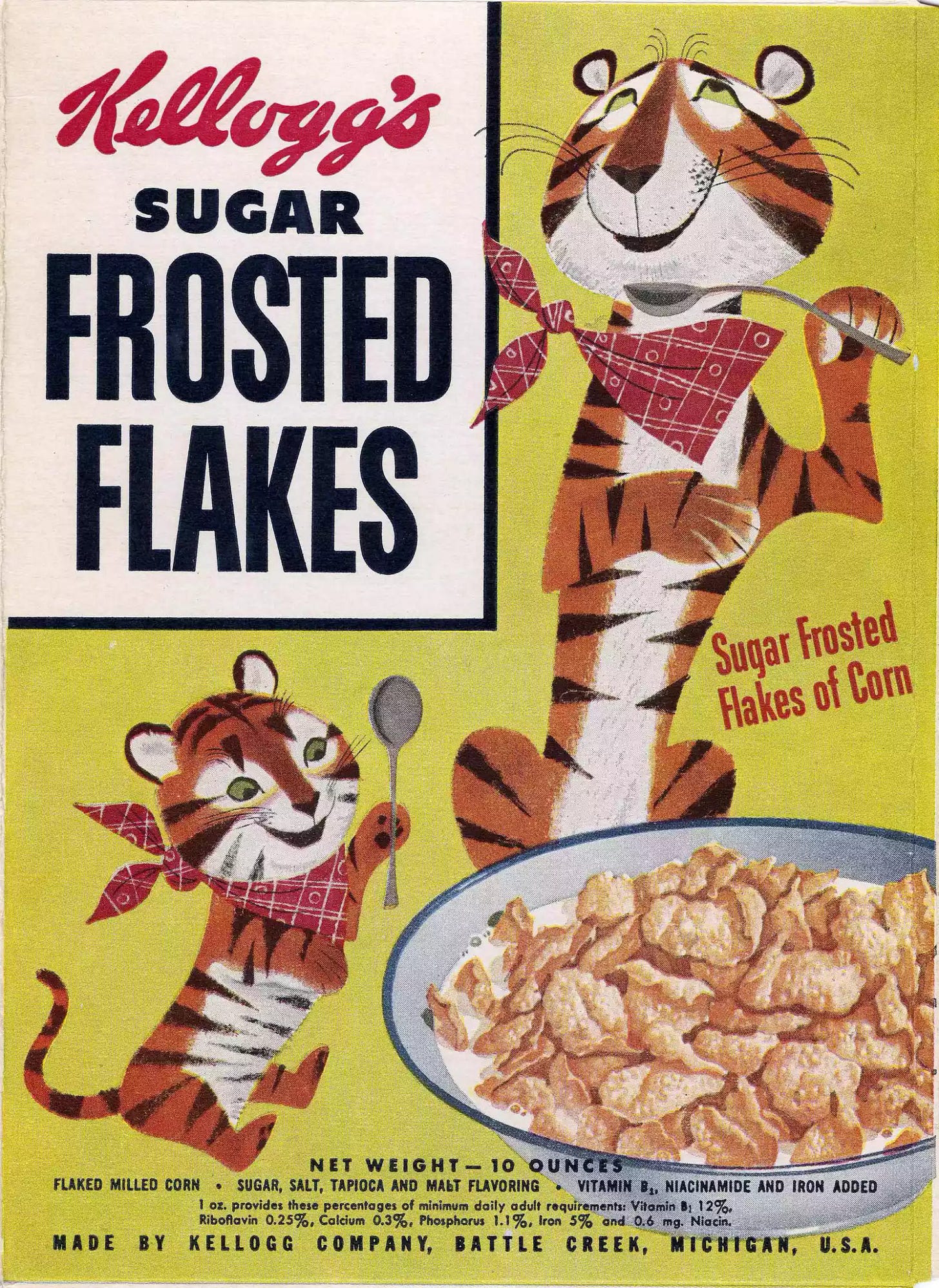

Later in the century, companies like Kellogg’s marketed sugar in their “healthy” breakfasts as an energy and flavour booster. When scientists discovered sugar’s preservative properties, it found its way into everything: snacks, canned vegetables, pre-cooked meals—you name it. Everything contained sugar.

The numbers tell the story: by 2000, global sugar consumption had increased 100-fold from 1850. The average person now consumed 23 kilograms of sugar annually—nearly triple the 8 kilograms consumed in 1800.

This explosion happened because production went into overdrive. In 1800, the world produced about 2 million metric tons of sugar. By 2000? 150 million metric tons. All that sugar had to go somewhere.

And so, everything still contains sugar, now.

But sugar’s history reveals a hidden truth.

Our primate ancestors learned to love sugar through a genetic mutation some 15 million years ago. Scientists believe that during a period of global starvation, we developed the ability to store sugar as fat—a survival mechanism. Imagine our ancestors spotting a bright, ripe fruit high in a tree: not just food, but a lasting energy reserve. This is how we came to get that dopamine hit from sugar. Back then, sugar was rare, found only in small quantities in fruits and flowers.

But we’re no longer in survival mode. Our bodies still get that same primal pleasure from sugar—the dopamine hit that kept us alive millions of years ago. Only now, through a convergence of economic, social, and political forces, sugar has transformed from a rare energy source into a concentrated, industrial product. It was never meant to be this way.

And our bodies? They haven’t caught up yet.

Sources:

- World of Sugar: How the Sweet Stuff Transformed Our Politics, Health, and Environment over 2,000 Years by Ulbe Bosma

- Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History by Sidney Mintz

- A Splendid Exchange: How Trade Shaped The World by William Bernstein