Is modern-day bread even food?

It’s not and here’s why.

The most trustworthy source of food and

fitness journalism in the country.

Editor’s Note: Hey there, Samarth Bansal here. I am the Editor of Truth Be Told, and writer for today’s issue, which explores our staple food for millennia — bread.

I remember being shocked when I first saw the ingredients listed on a bread label a couple of years ago. What had I been eating all these years?

That’s the story today: a guide to understanding the modern industrial bread and some tips to choose better from the infinite options available in the market.

As always, I look forward to your thoughts and feedback. Just reply to this email. Happy reading!

In his book Bread: A Global History, William Rubel shared a striking anecdote:

“A few years ago, I attended an international conference in which the bread workshop opened with the moderator throwing a loaf that had been purchased in a supermarket into a bin. It was an industrially produced bread; soft, white pre-sliced and pre-packaged.

To hundreds of millions of families worldwide this was good bread. But this loaf of bread was outside its community. To the group of people in that room it was not just bad bread: it was not food. It was trash.”

Oooh. Read that again: “It was not food. It was trash.”

Why would they say that? Why throw shade at plastic-wrapped pre-sliced white bread?

Because bread is not what it once was. The bread-making process has changed.

And it has changed so significantly that a baker from the late nineteenth century would not recognise the industrial bread we eat today as ‘bread’ —better to call it a bread-like substance.

Bread used to be a simple food with simple ingredients: flour, water, yeast and salt. Mix them until a stiff dough forms. Let the dough rise to allow for fermentation. Let the yeast do its job. And then, bake the dough into a delicious loaf of bread.

And now, bread is, umm, this.

This is not real food. This is ultra-processed food, just like chips, candy, and cola—heavily modified and contains a long list of complicated ingredients.

Bread went from four basic ingredients to now over a dozen.

Why?

To make bread production fast, cheap and convenient.

The ‘Chorleywood Bread Process’ created in 1961 revolutionised large-scale bread production: it introduced a combination of high-speed mixing, and addition of ingredients such as sugar, fat, and emulsifiers to produce a soft and fluffy bread with a longer shelf life.

The new process shortened the fermentation period and the time it took to make a loaf. Additives reduce the dough’s rising time from days or hours to just minutes. Special ingredients like quick-acting yeast allow for a bigger and faster rise.

One can argue that industrial bread is a humanity-advancing invention: as the population grew, more food was needed, and cheap and easily accessible bread solved the purpose.

But it has a cost: the bread most of us eat has lost most of its nutrients, including fibre. It’s now just simple starch, quickly turning into blood sugar in our bodies. And without high-quality fibre, it can’t nourish our gut properly.

Now look, this is not an article to make a case against eating bread. I mean…it can be read that way, but that’s not my intention.

I want to nudge a change in attitude.

Ask questions about the bread you eat, and demand better. Investigate the label. Look at the ingredients. Save yourself from bread scams—there are many. And make better choices from the wide range.

It’s pretty simple. But things make much more sense once you know what goes into your bread. So let’s look at that first.

One: Refined wheat flour, or maida

Look at the first ingredient on the label: refined wheat flour — or maida.

You probably already know: white bread is made with maida, and maida is nutritionally inferior to your regular atta.

Because refined flour is not a whole grain.

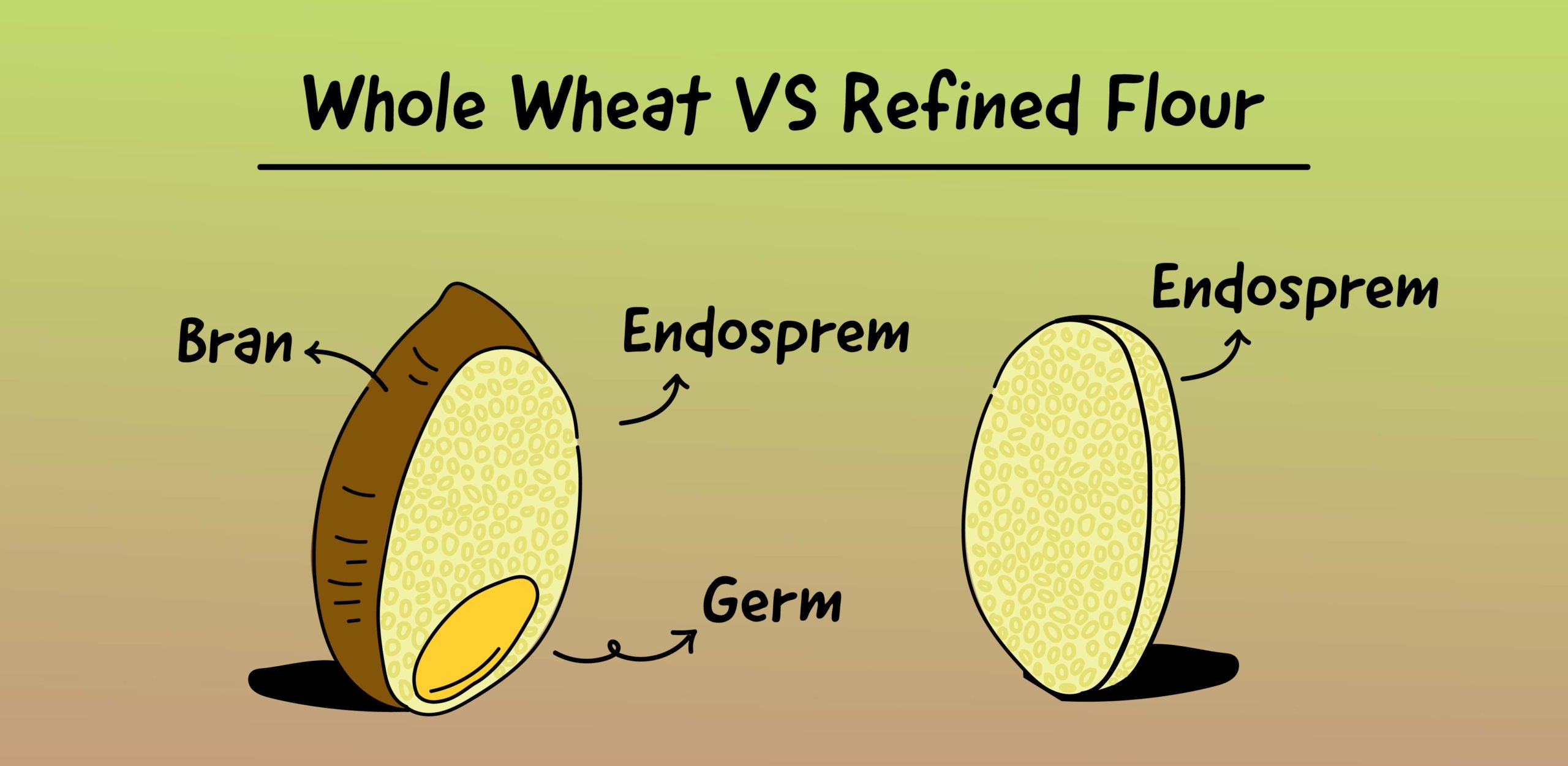

In making refined flour, a large chunk of dietary fibre is lost as the grain only contains the endosperm of the wheat plant and not the germ and the bran layers (which is where the real nutrition resides).

And it screws with your blood glucose levels, a key marker of metabolic health, which I had explained in a previous article.

[T]he whole-wheat base in Pizza A is superior from a nutritional standpoint because the ‘whole’ refers to ‘complex carbs’, the ones with a complex cell structure, so the body needs to do more work to break them down.

The longer it takes for food to digest, the slower it is absorbed in the bloodstream. So blood sugar rises slowly and steadily. It provides sustained energy and helps us feel fuller for longer.

It’s not the same for refined flour or maida. It’s digested quickly, and glucose rushes into the bloodstream. Sugar levels spike instantly. And a crash follows the sugar spikes.

Which is why the surging popularity of ‘brown bread’ instead of ‘white bread’ — but damn, that’s a scam in itself. More on that later.

Nothing better than sliced bread,’ except telling 2 friends the truth on bread. Share this!

Two: yeast boosters

Industrial bread is cheap in part because it’s made very quickly. How to do that?

Using yeast boosters.

Like sugar. See the second ingredient on the label.

Sugar sweetens the bread, yes, but it also feeds the yeast.

Yeast is like a tiny plant that needs food to grow. The food it likes to eat is sugar, and there is sugar in the flour we use to make bread. But sometimes the sugar is all mixed up and hard for the yeast to get to.

So adding extra sugar speeds up the task so the yeast can eat it right away and grow strong and happy. And so the dough rises quickly.

(Here is your regular reminder that “added sugar” is hiding in 74% of packaged foods — in supposedly ‘healthy’ salad dressings and stuff where you expect it the least: bread. In 2020, the Irish Supreme Court ruled that bread served at American sandwich chain Subway could not in fact be defined as bread because of its high sugar content.)

There are other boosters too.

For example, see “flour treatment agent” on the label. INS 516.

That’s a mineral additive: ‘calcium sulphate’. Calcium serves as a nutrient for the yeast, so the yeast can work fast and make the bread soft and fluffy, just like a cosy bed. It also helps keep the dough from getting too sour.

Three: Preservatives and fats for longer shelf life

Preservatives are substances added to extend shelf life, which allows the bread to be stored and transported over long distances without spoiling.

You will find preservative ‘282’ in the ingredient list above. That’s ‘calcium propionate’: it prolongs shelf life by actively inhibiting mould growth and other bacteria.

You will also see ‘refined palm oil’ on the label. It acts as a fat source, making the dough softer and more pliable, resulting in a finer crumb structure, and contributing to texture and flavour, making it more tender and appealing.

The fats in palm oil also help to slow down staling, which contributes to extended shelf life and maintains the freshness of the bread. Many bakeries use palm oil because it’s cheap and easy to find.

Bread will stay fresher for longer because of the added preservatives

Fourth: Dough conditioners

472E on the label is DATEM, an emulsifier added to bread dough to enhance its volume and softness. It improves the dough’s ability to retain air bubbles, resulting in a visually appealing baked bread. Primarily used in commercial bread production, DATEM ensures consistent appearance and flavour in every loaf.

Warn your friends about whats being added in their bread

And then there is some other stuff…

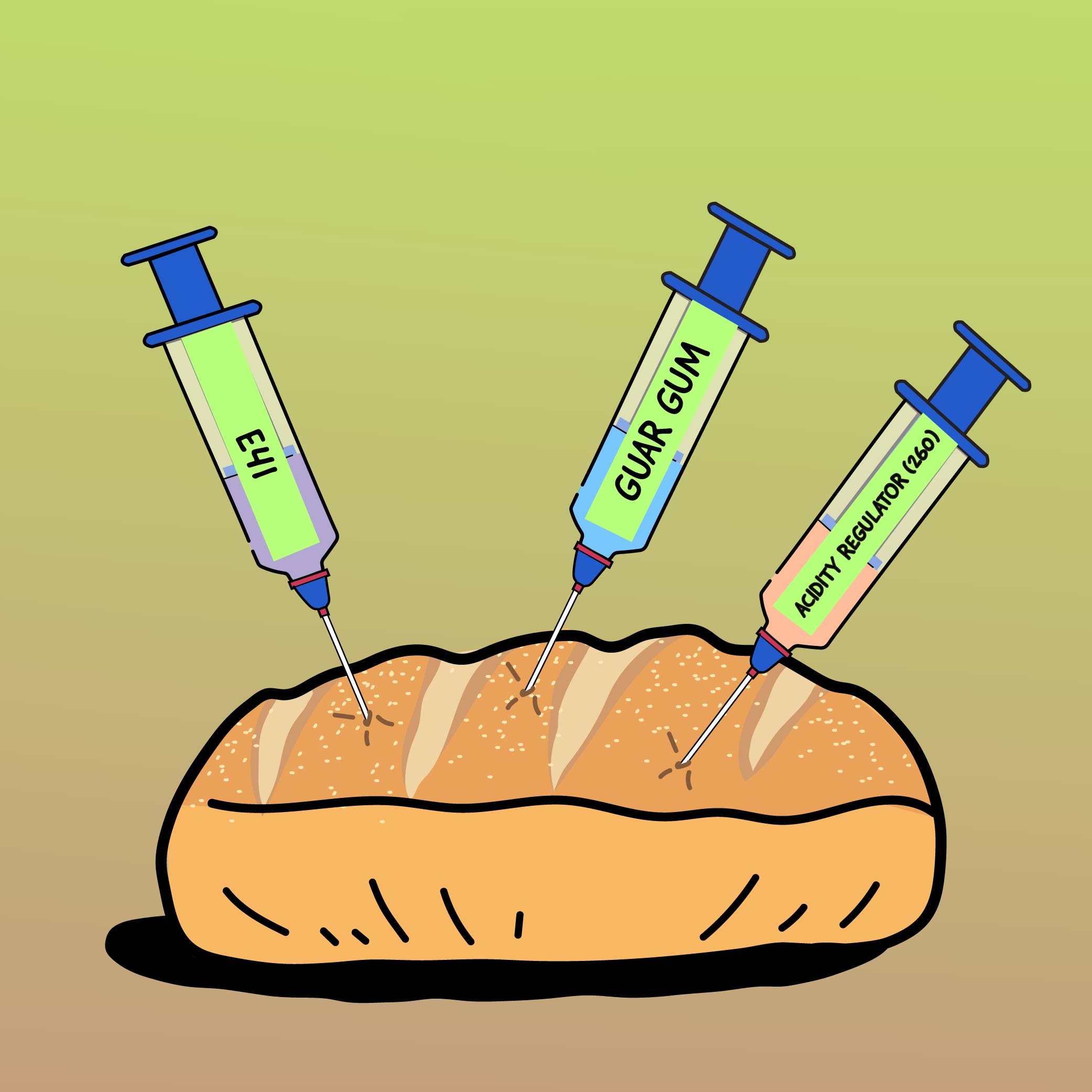

E41, guar gum, makes bread softer and last longer. The acidity Regulator (260) helps ensure the bread is not too acidic or too basic, stopping bacteria from growing.

This processing with non-essential ingredients — only flour, water, yeast and salt are the primary ones — ensures that the bread is soft, it’s produced quickly, and it lasts longer. And it’s cheap for both the maker and the buyer.

While the economic logic of adding all the ingredients is sharp, there is no hard nutritional logic. That’s not what industrial bread optimises for.

This is why it is a substandard product — and why the folks at the conference called it trash.

In a previous TBT article on smart food shopping and label reading, Shashank had explained why we don’t like foods with the E numbers and chemicals:

Now, not all chemicals are bad. Human beings created chemicals to make life easier, and some do that function. Take baking soda, or sodium bicarbonate. It’s been used for ages in cooking. Not bad. And yes, these additives have been deemed safe for consumption by your local food authorities, meaning you won’t die if you eat them.

But changing food’s colour, taste and texture changes our relationship with it. If something with no blueberries in it starts tasting like blueberries, our mind starts thinking, ‘oh great, fruit’ and starts having more of it. Same with something that isn’t brown but looks brown. Or something that becomes extra tasty with MSG.

So here is my personal rule: avoid numbers in food as far as possible. Keep the food real. Let the body understand what it is having and it’ll do nothing to harm itself.

That’s the problem.

Now let’s work towards the solution: What to do? How to get good bread? How to choose better?

Option One: Bake your bread at home with good-quality ingredients. Best. Great, if you can. But most of us can’t. I can’t.

Option Two: Buy from a local specialist bakery you trust. This is what I do: I live in a small hill town, and I order my bread from a new bakery that lies a few hundred metres away from my house. (It’s terrific!)

Note the word ‘trust’: most breads from local bakeries don’t come with a nutritional label. And who knows, that bread may be even worse than the supermarket variety? So ask and be sure. Local doesn’t automatically mean better.

But you may not have a trusted bakery near your house or have yet to learn of them. Or it is too costly for you. Or you have run out of bread and desperately need a sandwich in the middle of the day and have no option but to buy supermarket bread quickly.

How to choose the best one? Here are two tips:

Tip One: eating atta bread over maida bread

I explained the reason above: blood glucose control. Maida bread will likely have a higher sugar spike than regular atta bread.

But spotting one is tricky because of food marketing sorcery.

Most consumers assume that white bread means maida bread and brown bread means atta bread. Unfortunately no.

Most brown breads today are simply white bread plus molasses plus caramel plus brown colour.

Yup. It’s essentially a mixture of undesirables: maida mixed with brown colouring — INS 150a.

See the label below.

If you want real, nutritious ‘brown bread’, ask for ‘whole-wheat bread’.

Actually, no: ask for ‘100% whole wheat bread’ with zero maida. If it doesn’t say 100%, chances are that there’s some maida mixed in it. Turn the pack and read the label. And also check for INS 150a — the brown colour.

Tip Two: Look at the carb-to-fibre ratio

I learnt this tip in Tim Specter’s fab book, Food for Life: check the ratio of total carbs to fibre. Why?

Simple reason: you want a more fibrous bread for better glucose control.

That’s the problem with your maida bread: the milling process removes the fibrous nutritional stuff.

This metric quantifies that reality into a helpful benchmark: Professor Spector says a carb-to-fibre ratio (C:F) of less than 5:1 is ideal.

Here is a comparison of four varieties of Harvest Gold breads:

Going by the C:F metric, there is no difference between white and brown bread. Their whole wheat bread is better but doesn’t meet the 5:1 benchmark that Spector recommends. But their multigrain bread does. So among these four, you know what’s the best.

I like this metric because it is a relatively straightforward way to navigate labelling trickery.

Point to note: While researching for this piece, I found many brands that don’t even declare the fibre data on their white bread. From the little I know about labelling regulation, fibre declaration is not mandated by law — until you make a ‘high-fibre’ type health claim. But my takeaway after observing the selective declaration of fibre data is that it’s likely so low that they didn’t want to reveal it.

Learning about the changes in bread production and understanding ingredients really helped me in choosing better. Sometimes I do end up buying and eating bread I don’t feel great about. But because I know it’s nutritionally deficient, I cap my intake at two slices max in a day, and ensure I pair the bread with protein and good fat. It’s all about awareness. That’s it.

Fresh out of our Truth be Told oven- share this hot piece to 2 hot friends 😉

More from Truth Be Told

Why you can’t eat just one chip

The Definitive Guide to Smart Food Shopping

You can’t be ‘healthy’, if you don’t know what it means

Should you count calories?

Safest cooking utensils for healthy living

Eight swaps to eat better everyday

Does refrigeration kill nutrition?

Everyone has an opinion on your body. But why?

8 tips to choose the right cooking oil

Beware: New Year marketing is here!

Diwali indulgence won’t make you fat