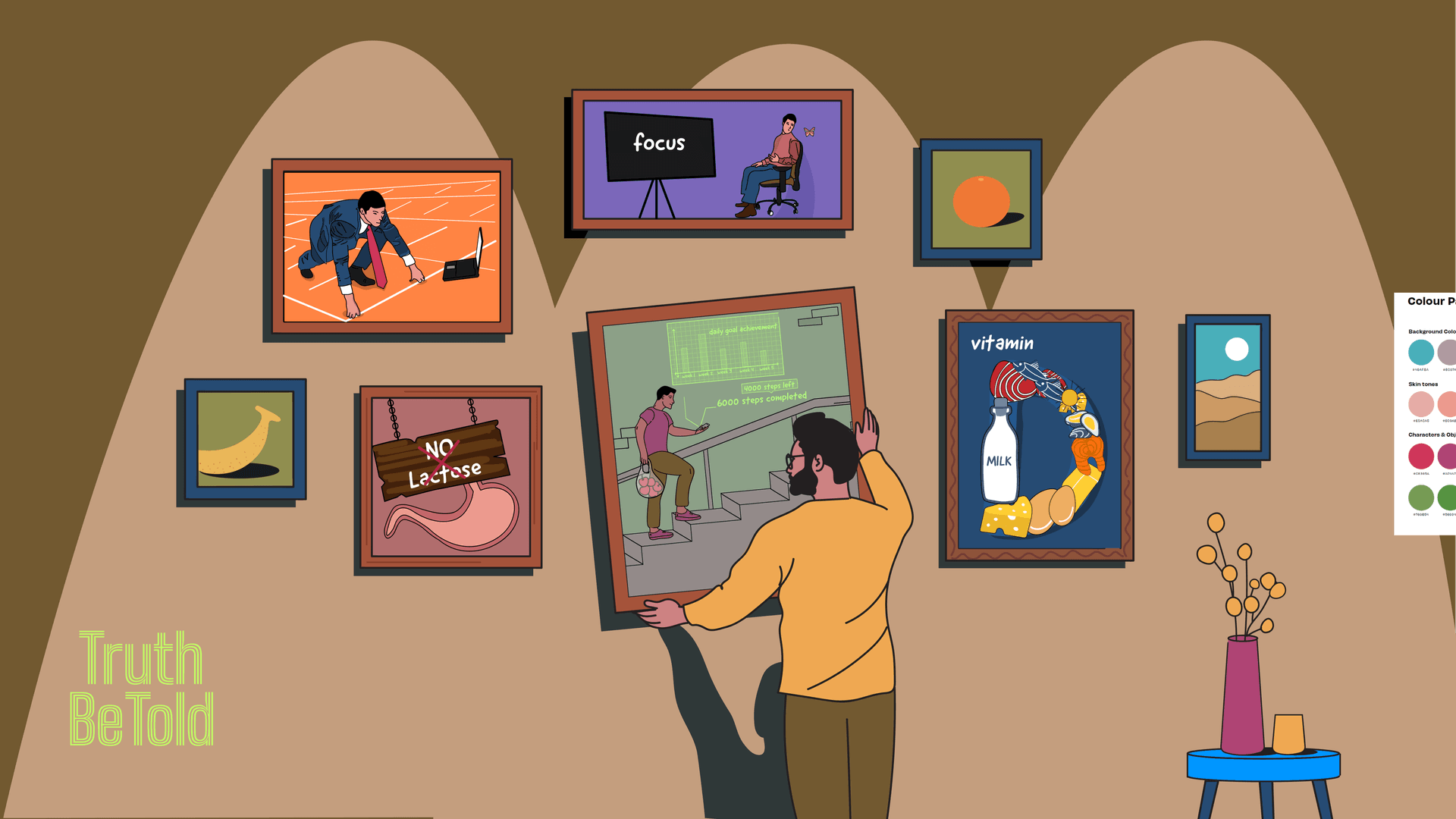

Rapid Fiver: Is 10k steps a myth? And four other things to know!

The most trustworthy source of food and

fitness journalism in the country.

Editor’s Note: Hi there! Samarth Bansal here, your Editor. Today, I am writing our curated edition where we share our favourite health content from outside the TBT universe. Five things.

One: ‘10k Steps a Day’ is a Marketing Myth

Most of you’ve heard it and some of you swear by it: the idea that we should all aim for 10,000 steps per day as a fitness goal. What many of you might know—I didn’t until recently—is that this number is largely a marketing construct and is not based on solid scientific evidence.

Here’s the origin story: In the 1960s, the Japanese company ‘Yamasa Clock’ created a pedometer (i.e. step-counter) to capitalise on the fitness craze emerging in the run up to the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. Those guys came up with the 10,000 steps a day recommendation as the target number of steps people should take to promote their device.

How did they arrive at this magic number? Hold your breath: Because the Japanese character for 10,000 looks like a person walking. See for yourself.

Source: TrungTPhan X account

I find this a bit amusing. I have had my phase of peak obsession with hitting the 10k number—9k would make me feel like a douchebag—only to know that some person, sixty years ago, just got a visual inspiration from a Japanese character? Lol.

No wonder they named the device ‘Manpo-kei’—which means ‘10,000 steps metre’ in Japanese. Clearly, the messaging worked: the number persists in popular consciousness till date.

What to make of it? Three thoughts from me:

1) It’s a reminder that numerical targets in fitness are promoted despite limited scientific backing. It helps—when you have mental bandwidth and interest—to question what’s considered normal. New research claims that 7,500 steps a day might be just as useful.

2) Yet, I do think this number actually helped me during my fat loss phase to serve as a useful reminder to move more. And helped me add consistent movement through the day. As in trying to hit this arbitrary number revealed my sedentary habits. So I started looking for opportunities to walk—many of which have stuck till date: always taking stairs instead of elevators; parking a little away to walk a bit; walking during calls when machines are not needed. So I don’t feel too pissed off with it either.

Forward this to 1̶0̶k̶ 7500 people 😂

Two: A Fresh History of Lactose Intolerance (The New Yorker)

This story in The New Yorker offers a fascinating review of ‘Spoiled’ by Anne Mendelson, a book that explores the historical and cultural context of milk consumption. (It’s paywalled—so I have uploaded a PDF here.)

It traces how this myth originated: Milk drinking started in prehistoric Western Asia and Northern Europe, where a genetic mutation allowed some adults to digest lactose, meaning people in these geographies could now digest fresh milk.

However, Mendelson writes, for most outside these regions, lactose intolerance is the norm—tolerance is the exception.

And yet, despite this evidence of widespread lactose intolerance—especially among non-European populations—milk has been marketed as a nutritional necessity, demonstrating how societal and commercial forces shape health beliefs. She traces how, as colonial powers like Britain expanded, they spread the faulty belief that all people could digest fresh milk.

To be sure, the article is not making a blanket case against drinking milk or dairy (that’s a separate discussion). It cites examples, like in India, where fermented milk—rather than fresh milk—has an important place in the cuisine, like dahi, paneer and chhena.

In short, Mendelson argues the myth that all people require fresh milk ignores science and the reality of lactose intolerance. She advocates re-examining this myth and considering alternative milks.

For me, there is another lesson here: Just like the previous example of 10,000 steps being a marketing construct, normalisation of dietary beliefs can emerge from limited evidence that is over-generalized. In this case, a genetic trait in some populations was wrongly assumed to apply to all.

Societal attitudes and early traditions acquire an authoritative status as “normal” over time, even if based on limited knowledge. And in that sense, this piece nudges us to be more mindful of nutritional orthodoxies.

Three: How One Disease Changed What We Know About Medicine— Twice

Too much of something good can be bad. Doctors learned this when they tried to prevent rickets in kids by adding lots of vitamin D to food. (Rickets is a bone disease caused by vitamin D deficiency.)

However, they then discovered the problems caused by excess vitamin D, like high calcium levels in the blood, leading to kidney problems. It took many years to understand why.

This video talks about two studies that get into the reasons—and evolving understanding—of why more-than-needed levels of vitamin D affect some kids but not everyone.

1) In a 2011 study, researchers found that certain kids have differences in their DNA that make it hard to process high doses of vitamin D. These DNA differences are a mutation in a gene called CYP24A1.

This gene helps the body manage vitamin D by breaking down any excess. However, the mutation can stop this process, leading to too much vitamin D in the body. People with this mutation can’t properly control their vitamin D levels, which can result in high calcium levels in their blood, kidney problems, and other health issues.

2) Then, in a 2023 study, researchers focused on those who still had problems with excess vitamin D but didn’t have the mutation. This one is a bit technical, but here is the gist.

There are protein-coding parts of DNA and non-coding parts. The protein-coding parts contain instructions to make proteins, which do most of the work in our cells. That’s why scientists used to think only those parts mattered. And the non-coding parts were assumed to be “junk” DNA without important functions.

But the 2023 study revealed that even these non-coding parts—which make up 98% of our DNA—can play an important role. It can cause disease by affecting the body’s complex chemistry.

The lesson here? When we try to “fix” dietary deficiencies with fortified foods or supplements, there can be unintended consequences. Our bodies are complex systems—and each body responds uniquely. New forms of foods or high doses of nutrients may have different effects compared to getting them naturally through diet. (It’s unlikely that vitamin D from sunlight would lead to an excess.)

✌We have now reminded you twice to share this article

Four: The Making of a Corporate Athlete (Harvard Business Review)

There is a whole subculture of online conversation dominated by productivity hacks, from time management methods and note-taking tips to the best planner apps and deep-work strategies.

What they often miss—or don’t emphasise enough—is a more holistic approach to being better in the workplace, which includes physical fitness. This is why I love this 2001 article from HBR, which, I can confidently say, remains as relevant two decades later.

The writers built a framework for working professionals with demanding lives, taking inspiration from athletes, on how to achieve their ‘Ideal Performance State’.

…our integrated theory of performance management addresses the body, the emotions, the mind, and the spirit. We call this hierarchy the performance pyramid. Each of its levels profoundly influences the others, and failure to address any one of them compromises performance.

I don’t want to list the key takeaways as a list—it will only make sense if you take out twenty minutes and read the whole damn thing.

Instead, I will leave you with a note from Siddharth Raman—CEO of Sportz Interactive, a sports tech and marketing company—who shared this piece in our ‘Truth Seekers’ WhatsApp community group:

“I came across this article as part of a management training program in 2016. Being a sports fan and a big believer in sport being a metaphor for life, the premise of this article was a light bulb moment for me to focus on my physical, emotional, mental and spiritual capacity.

The focus has been on building workday rituals across each of these. The biggest impact has been on my exercise (primarily running) and food habits (what, when, and how I eat).

It’s easy to see this in hindsight, but parallels can be drawn between my running and professional journeys ever since I started applying the concepts in this piece. As I have gradually stepped up from running 10ks to half and now full marathons, my career has evolved from being an individual contributor, to managing teams and now being the part of a leadership team of an organisation.

The constant through this journey has been, and hopefully continue to be, the focus on strengthening capacity and not compromising on recovery.”

Grateful to Siddharth for sharing this. And on this note, an open invitation: if there is any piece of health writing—anything—that spoke to you deeply, in the sense that you feel compelled to share it so more people can read, please send us a link!

Five: How to Reclaim Your Attention—and Focus

I’ll end this week’s edition with a podcast: an episode from the Ezra Klein Show (produced by the New York Times). And it’s not about physical fitness—it’s about mental fitness.

Klein interviews Gloria Mark, a researcher in the field of attention at the University of California, Irvine.

I know there’s been a lot of talk about attention everywhere. I’ve been hearing about it for at least six years now. What I enjoyed in this podcast were three specific things.

One, Mark looks at attention from a lens beyond productivity—which is how most discussions are framed. Instead, she asks us to think about attention as a factor of well-being (which is why I am linking to it.) Second, they discuss a lot of empirical data on the impact of tech on stress levels—not just hypothetical talk. Third, they suggest potential ways to figure out how to reclaim our attentional well-being.

They get into data on changing attention spans, the importance of managing interruptions, implications for children, the value in recognising personal attention rhythms and the Japanese concept of ‘Yohaku No Bi’—the beauty of empty space. And more.

You can find it wherever you get your podcasts, or read the transcript here.

That’s it for this week. Happy reading, watching and listening!

If you have reach here, thank you attention span and spam everyone🙂