Why is my food a chemical cocktail?

The most trustworthy source of food and

fitness journalism in the country.

You know those people online who are always urging you to scrutinise nutritional labels on packaged food? They warn you about ingredients that sound like they’d be more at home in a chemistry lab than in your home kitchen — think ‘maltodextrin,’ and ‘xanthan gum,’ or those mysterious E-numbers and artificial colours.

Well, spoiler alert: I’m one of those ingredient vigilantes who turn label-reading into a full-blown detective hobby. I’m in the camp that believes if you can’t pronounce it, maybe you shouldn’t be eating it. Eat natural, avoid artificial.

This approach is core to my food philosophy. (And it’s a view shared by The Whole Truth, the company that publishes this newsletter – so account for that as you read.)

But let’s be clear: this is a debatable position. Are these additives really that bad? Haven’t the food safety regulators approved them? Does it matter if they’re consumed in small amounts?

In today’s piece, I will explain why I make a conscious effort to avoid ‘chemicals’ and ‘additives’ in my food, and why you might want to give it some thought too—but for the right reasons.

I got more clarity on this topic while reading Chris van Tulleken’s new book ‘Ultra-Processed People: Why Do We All Eat Stuff That Isn’t Food … and Why Can’t We Stop?’ — and I will mostly be referring to things I learnt while reading it.

1) All food is made of chemicals. So what’s the big deal?

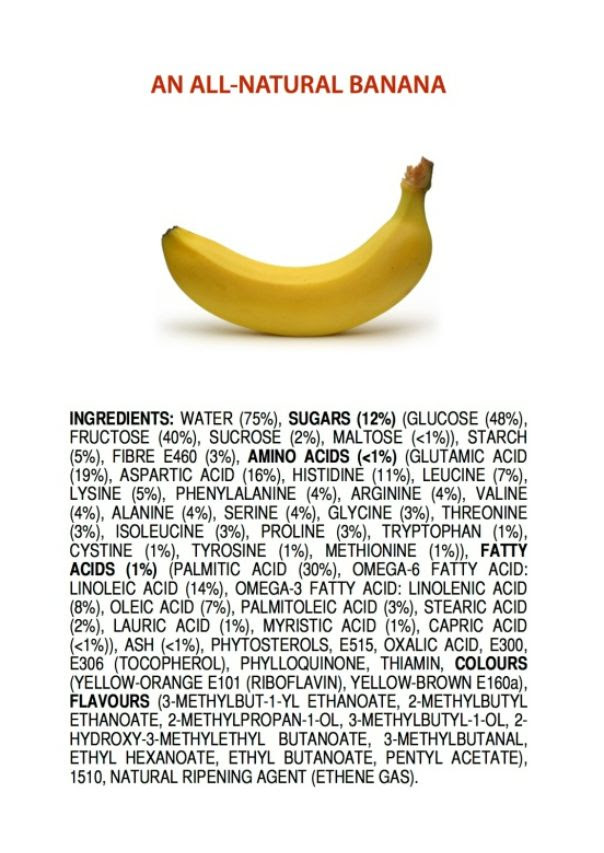

Sometime last year, I saw this eye-opening illustration of a banana with an ingredient list as if it were a packaged food.

What is a banana even made of ?

This visual, created by Australian chemistry teacher James Kennedy, cleverly highlights that all foods, even natural ones like bananas, are chock-full of chemical compounds. Water is H2O, and glucose is C6H12O6 – both chemicals, naturally occurring in what we eat.

Kennedy’s point was clear: natural foods, like bananas, contain a complex mix of ingredients that might look intimidating but are perfectly normal and safe. As he wrote on his blog: “With this diagram, I want to demonstrate that ‘natural’ products are usually more complicated than anything we can create in the lab.”

So, if everything we eat is made of chemicals, why fuss over synthetic additives?

Alright, here’s the thing: there’s a big difference between the stuff you find naturally in a banana and the synthetic things thrown into ultra-processed foods.

Take xanthan gum, for instance. I learnt about it in the book ‘Ultra-Processed People,’ I mentioned above. It’s a common additive you’ll find in many products, from toothpaste to salad dressings. This substance is an exopolysaccharide, basically a sugary slime secreted by bacteria.

While it’s great for thickening products, researchers have found that it also feeds a specific type of bacteria in the human gut. This bacterial species, surprisingly, is primarily found in populations consuming xanthan gum – it’s virtually absent in remote hunter-gatherer groups. The introduction of this bacteria could potentially disrupt the delicate balance of our gut microbiome – that’s the complex community of microorganisms in our digestive system crucial for our overall health. (For more on gut health, check out our earlier two pieces here and here.)

But the story doesn’t end with xanthan gum. Other additives like trehalose and various emulsifiers, previously considered safe, are now being linked to changes in gut bacteria and even to outbreaks of diseases like Clostridium difficile. These findings underscore the potential for synthetic additives to upset the balance between good and bad bacteria in our gut, a balance vital for what we call gut health.

This brings us to the heart of the matter: while natural foods contain complex but familiar chemical structures, additives like xanthan gum introduce new elements to our diet that our bodies – and our microbiomes – may not be fully adapted to. Their long-term effects, especially in combination with other additives, remain uncertain.

So the real worry with synthetic additives isn’t just that they’re ‘chemicals.’ It’s how they’re used in foods — in unfamiliar ways that our bodies might not recognise.

That’s why some of us get wary. It’s not about being scared of chemicals; it’s about being cautious with these new, man-made additions to our food.

Xanthan gum is used in your salad dressing… and also in glue. Let your friends know!

2) Haven’t they been approved by regulatory agencies?

When we think about food additives, we often find comfort in the idea that they’ve been approved by regulatory bodies. But the reality is more complex. Let’s look at how this works in the USA with the FDA (Food and Drug Administration), which is similar to India’s FSSAI but is often viewed as more stringent.

There’s a category for food additives called GRAS, standing for ‘Generally Recognized As Safe.’ This was initially meant for obvious items like vinegar or salt to bypass lengthy approval processes. However, as highlighted in “Ultra-Processed People,” this system has its pitfalls.

A striking example is Corn Oil ONE, a product that faced scrutiny. The company behind it, while seeking GRAS status, mistakenly submitted the molecular structure of an HIV drug, Lopinavir, instead of their corn oil. This mix-up, noted in their FDA submission, raises serious concerns about the accuracy and thoroughness of their safety assessments.

Food regulatory bodies have a complicated process to approve foods and additives

You’d think the FDA could then inspect the company’s facilities, similar to what they do with drug companies. However, the way the GRAS (Generally Recognized As Safe) system is set up, if a company asks the FDA to stop evaluating an additive, they can still proceed to use it in food. This is exactly what happened with Corn Oil ONE. Despite the FDA’s concerns and the company’s questionable submission, there was nothing stopping them from marketing their product as safe, relying solely on their internal scientists’ judgement.

This isn’t an isolated incident. According to Van Tulleken, the author of the book, since 2000, there have been only ten applications to the FDA for full approval of a new substance. Meanwhile, there have been 766 new food chemicals added to the food supply i.e. 98.7% of new chemicals were self-determined by the companies that make them. This means they didn’t go through the full FDA approval process and instead relied on their own assessments.

Another case in point is the ongoing debate on titanium dioxide (E171), a chemical used as a colour additive in foods. While the EU has banned it over concerns of potential DNA damage and cancer risk, it remains approved for use in the US. This stark difference in regulation between two major authorities highlights the uncertainties and inconsistencies in food additive safety standards.

To be clear, I’m not suggesting a conspiracy or negligence on the part of regulators. I know regulation is hard. My point is that these kinds of discrepancies don’t exactly inspire confidence.

This is why I advocate for the precautionary principle: when there’s doubt about the safety of certain additives, I prefer to err on the side of caution. Given the complexity and uncertainty surrounding food additive safety and approval, I choose to avoid ultra-processed foods, or any food loaded with additives. It simplifies decision-making.

Make friends join FDA: Foodie Detectives Association 😉

3) So why are they in my food?

Understanding why food companies use additives in ultra-processed foods convinces me I must avoid them to whatever extent possible.

It boils down to economics and practicality. Let’s take the example of ice cream – a familiar treat with some surprising truths behind its creamy facade.

Van Tulleken narrates his conversation with Paul Hart, a food-industry insider — he worked at Unilever for over twenty years — who explained the role of additives like emulsifiers and gums in ultra-processed foods. These ingredients don’t just enhance the texture; they cut significant costs.

For example, they make ice cream tolerant to temperature changes, facilitating its journey from the factory to your freezer. By preventing ice crystal formation and maintaining creaminess, these additives allow for centralised, large-scale production and less stringent temperature control during transportation.

Paul compared American artisanal ice cream brands like Cream o’ Galloway, which use traditional ingredients (milk, cream, sugar), to mass-produced brands like Ms Molly’s.

The artisanal brand’s ice cream, less tolerant to temperature fluctuations and transport stress, remains a local product with a higher price tag. In contrast, Ms Molly’s leverages additives and synthetic ingredients to imitate the qualities of traditional ingredients, but at a much lower cost.

This is where the concept of molecular mimicry comes into play: It involves using chemically engineered substances to replicate the taste, texture, or nutritional value of natural ingredients, such as substituting natural milk fats with modified vegetable oils or lab-developed proteins. These alternatives are cheaper to produce and acquire, yet effectively imitate the characteristics of their natural counterparts.

Food companies may add chemicals and additives to cut costs, not enhance nutrition

In ultra-processed ice creams, the aim is to emulate the creamy texture and rich flavour of traditional ice cream, usually made from real milk and cream, but at a reduced production cost. With a strategic use of additives and synthetic substitutes, ingredients work together to replicate the smooth, rich qualities of traditional ice cream while ensuring stability and longevity, all of which contribute to a lower overall cost and greater commercial feasibility.

This approach extends beyond ice cream, being a prevalent practice across various ultra-processed foods. It’s not just about creating new textures or enhancing taste; it’s a cost-saving strategy. These additives allow for extended shelf life, easier distribution, and can even drive overconsumption. (Check out our earlier piece on how the same practice has helped companies produce bread at scale.)

By understanding molecular mimicry, we see the economic logic behind the prevalence of additives in processed foods. They’re integral to a business model that prioritises cost efficiency, often compromising the natural integrity of food products.

All of this begs the question: why consume these products if we don’t have to? Is it really necessary to? Why not choose simpler, less processed foods?

This is the crux of my message: be cautious about foods with ingredients that sound more at home in a chemistry lab than in your kitchen. Let these complex, hard-to-pronounce substances stay where they belong – in scientific experiments, not in our daily meals.

By choosing foods with simple, recognizable ingredients, we’re not just making a dietary choice; we’re making a statement about the kind of food system we want. So, the next time you’re about to pick up a food item, take a moment to read the label. If the ingredients sound like a chemistry puzzle, maybe it’s best to leave it on the shelf.

“Add” some value to your family WhatsApp group. Share now 🙂

More on Truth be Told

A masterclass on managing caffeine: How much coffee is too much?

Are energy drinks bad for you?

Do men lose weight faster than women?

Does refrigeration kill nutrition?

Everyone has an opinion on your body. But why?

How I took on the Herculean task of reinventing my body

I finally started taking care of my body