Will Bournvita allow us to talk about sugar?

What is the Cadbury Bournvita controversy? Is Bournvita sugar content healthy for kids? And are we allowed to talk about this?

The most trustworthy source of food and

fitness journalism in the country.

Editor’s Note : Hey there, Samarth here, the Editor of Truth Be Told, and the writer for today’s issue, where I zoom out to discuss our sugar-laden food environment, with a focus on the ongoing Bournvita controversy.

Please note that The Whole Truth, which publishes this newsletter, competes with Mondelez, the parent company of Bournvita, in the chocolate category. While the editorial operations function independently of the company’s product operations (read our manifesto), I want you to be aware of this potential conflict of interest. However, I assure you that there is no intention to malign any brand or company, and the views expressed in this article are solely my own.

An odd thing happened last week.

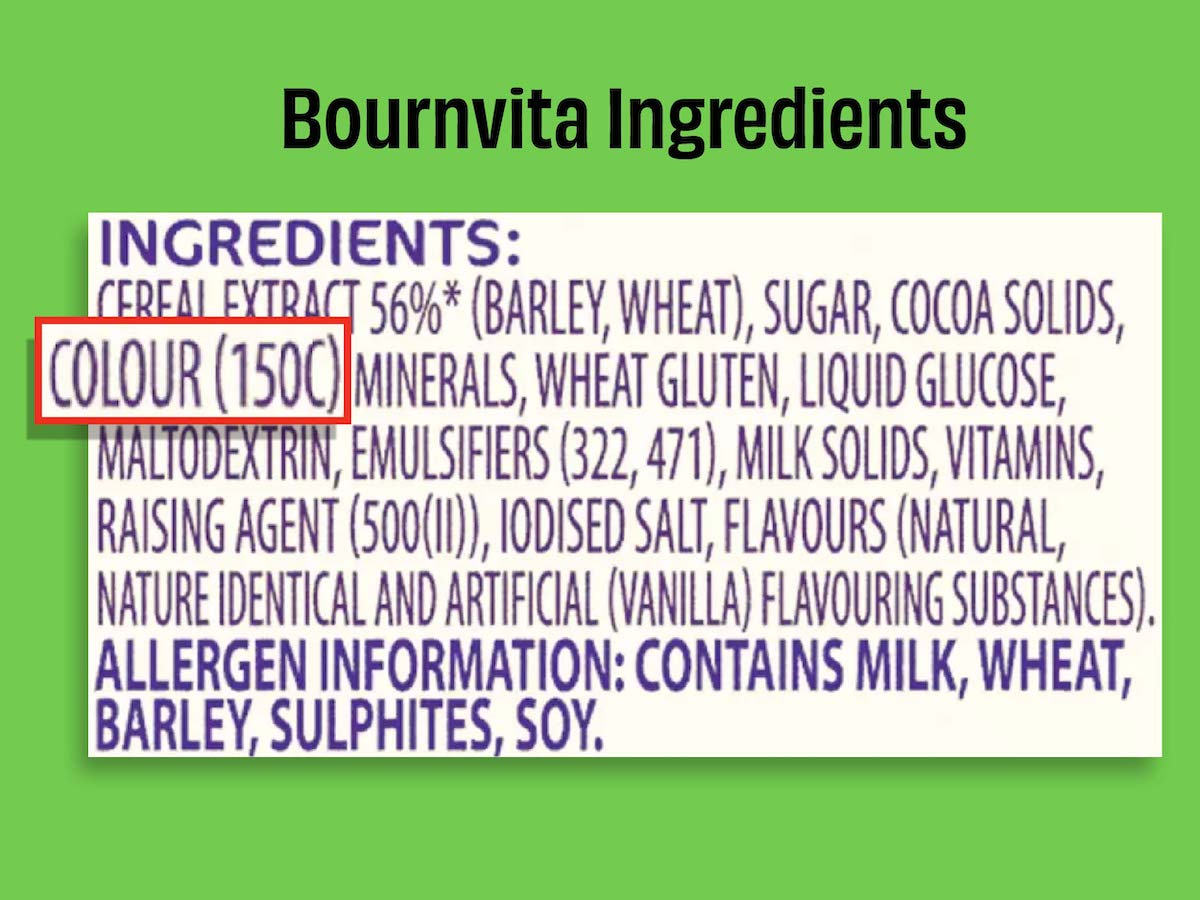

Food educator Revant Himatsingka (@foodpharmer) told the world out loud what Cadbury had already told the world on the back of Bournvita’s pack: the popular chocolate-flavoured malt drink is about 50% sugar.

“How is this helping your brains? How is this helping your immunity? How is this even legal?” he asked in a 90-second Instagram reel and urged the government to take action against “false claims”.

The post went viral, with nearly 1.2 crore views. A cricketer-turned-MP tweeted that he may want to take up this issue in court: “After listening to this video about Bournvita, I will be consulting my lawyers and will file a case for defrauding the people.”

The company was expectedly not pleased. They called in their lawyers and served the influencer a legal notice “to avoid misinformation.” They also posted an Instagram statement emphasizing Bournvita’s nutritional value. (They turned off comments, though.)

So Revant deleted the post. Which made even bigger news and an even bigger PR disaster for Cadbury. That’s how I learnt this guy had called out the nostalgic Koi-Mil-Gaya featured drink I grew up with.

Now look, I am a journalist, and the lopsided power dynamics of David vs Goliath battles get under my skin. Drives me nuts.

I mean, yeah, Revant did some borderline scaremongering at the 40-second mark by saying that one of Bournvita’s ingredients, the caramel colour E150-C “is known for causing cancer and reducing immunity” — which, from what I know, does not reflect the current consensus of some regulatory agencies. Not a fan of additives, but this is an overreach.

I get that. But a legal threat?

So to let off some steam, I did what any sane person would do: I ranted about this incident on Instagram. (For relief’s sake. Always works.)

But the next day, as I calmed down, I realised that many of us had missed the point. We were missing the forests for the trees.

Because Bournvita is NOT the problem.

Wait, wait, hold up. Just to clarify, I have no relationship with Cadbury other than the fact that I’ve been known to use their chocolate bars as bribes. That’s about it.

But seriously, while Bournvita may be in the spotlight now, it is not the problem—the food environment in which it exists is the problem. The root of the problem lies in a food system that prioritises profits over people’s health, resulting in products saturated with sugar, salt and fat.

This is not the first time we’ve seen this; it certainly won’t be the last. So allow me to take you back in time for some history lessons and show you three consistent patterns.

Soak it all in, and then think about Bournvita.

Cool?

Let’s get started.

One: Everything is candy

25 gms. Remember this number. It’s the maximum ‘added sugar’ intake that you should consume in a day. (Read the footnote in the end to know about this. It’s not that simple.)

Just to be clear, look at two definitions: ‘Total sugar’ is the total amount of sugar in a food or drink, including naturally occurring sugar and added sugar. ‘Added sugar’ is the sugar that is added to food or drinks during processing, cooking, or at the table. For instance, fruit juice contains ‘natural sugar’ from the fruit, but also ‘added sugar’ in the form of high fructose corn syrup or other sweeteners.

Now what does 25 gms of added sugar look like in your favourite drinks and snacks? Brace yourself.

A 300ml can of Coca Cola? 33 gms of sugar. One can in, and boom: daily quota exhausted.

A 200ml tetra pack of ‘Real Mango Juice’? 23 gms of added sugar. Almost there.

A tall (354ml) Java Chip Frappuccino at Starbucks? This ‘coffee’ has 42 gms of sugar, meaning eleven teaspoons of sugar in just one glass.

This doesn’t sound like coffee. More like candy.

But know what?

If you keep this 25 gms benchmark in mind and start reading labels, you will notice what everyone in the industry knows but you probably don’t: everything is candy. There is just too much sugar (often hidden) in the food you eat.

This was not inevitable. Food companies made this happen.

It’s best illustrated by the story of how breakfast cereal was sweetened, which is a tale of betrayal and family feud.

In the early 1900s, the Kellogg brothers, John and Will, were running their successful cereal business together. They had started the Sanitas Nut Food Company, which produced unsweetened cereals. John was a staunch believer in health and wellness and refused to add sugar to their products, while Will had different ideas.

In 1906, when John was away on a medical-science trip to Europe, Will saw an opportunity to add sugar to their corn flakes mix. He did so in secret, and the sweetened cereal was a hit. However, when John returned and discovered what had happened, he was furious with his brother for going against the company’s principles.

So Will struck out on his own, selling the sweetened cereal under the name ‘Kellogg’s Toasted Corn Flakes’. The brothers fought for the commercial rights to the family name in court twice, with Will ultimately prevailing and registering his own company under the new name on December 11, 1922. That’s the ‘Kellogg’s’ which is now a pantry staple in our homes.

This was the start of a trend as manufacturers started adding sugar to almost everything. Sugar is like a magical enhancer that makes everything taste better, and to make matters worse, it’s addictive. It’s a habit-forming substance. No wonder food companies are obsessed with adding it to everything.

As kids switch from one processed food to another, they develop a taste for sugary foods, leading to the expectation that all food should be sweet. So give them something savoury, like vegetables, and they make faces like they just ate something rotten. They don’t like it. Because taste buds rewire based on what we feed them.

Like what you see so far?

Get TBT articles in your inbox every Saturday

What about Bournvita? How much sugar?

Depends on how much you consume.

The company says one serve, which they define as 20 gms powder, is not that much.

“Every serve of Bournvita has 7.5 grams of added sugar…This is much less than the daily recommended intake limits of sugar for children,” Cadbury said in their Instagram post.

One thing though: the company has splashed “50% of Daily Vitamin D” claim on the front of the pack based on two serves in a day, so it’s fair to assume they recommend two serves a day, right?

Now incidentally, that is also the amount I consumed in my childhood every day, which means I was exhausting more than half of my daily added sugar quota (15gms of the 25gms) by drinking this healthy drink alone.

Make of it what you will.

Two: Candy is sold as healthy

In the world of food marketing, adding a few vitamins can turn a laboratory product “healthy”. (Their words, not mine — but does “healthy” mean anything at all? Read our earlier piece on this.)

Take Tang, for example, which is also a Cadbury product. Originally a synthetic juice invented in a lab in Hoboken, New Jersey, it was transformed into a breakfast drink that promised all the health benefits of orange juice. Michael Moss tells this story in his excellent book: “Sugar, Salt and Fat”.

The initial goal was to replicate the nutritional profile of real orange juice. And the scientists in the lab did create a drink that tasted just like Valencia oranges. But adding all the necessary vitamins and minerals made it horribly bitter and metallic.

That’s when marketing director Howard Bloomquist stepped in and pointed out that people mainly associated orange juice with vitamin C—not all the other nutrients they were trying to add. And as technicians would soon find, vitamin C was that one nutrient they could add without affecting the taste.

And just like that, orange juice became Tang.

One serving of Tang? 16 gms of added sugar. Candy or not? You decide.

Like what you see so far?

Get TBT articles in your inbox every Saturday

It’s hard to find products in the supermarket that don’t make health claims: high-protein, low-sugar, no-preservatives, diabetic-friendly, keto-friendly, packed with antioxidants, iron-rich, and so on. Ignore every claim.

As Tim Spector wrote in his book Spoonfed:

There are now a large number of stealth junk foods that are increasingly marketed as health foods.

A great example are fruit yoghurts, which have seen massive increases in sales in thirty years, but are packed full of sugar, artificial sweeteners and fake fruit chemicals. To make the yoghurts ‘healthy’, the manufacturers strip out the fat and replace it with sugar or sweeteners, allowing them to market the yoghurt as ‘low fat’, despite them being unhealthy.

In India, take, for example, Mother Dairy Mango Yoghurt: just a 100 gm serving —one small pack—has 12 gm of added sugar. Half of the daily quota is done. Amul Stirred Fruit Yoghurt? Milky Mist Fruit Yoghurt? Same. 12-13 gms of sugar each.

Candy or not? You decide.

Bournvita just follows this pattern: “50% of daily vitamin D” says the front of the pack. Lots of sugar, but with some vitamin D.

The Bournvita pack says more: that it’s a “scientifically designed formula.” Let’s talk about that.

Three: The sugar-coated half-truths

How does one trust the supposed science behind bold claims which the food industry makes?

The food industry has long been known for its dubious marketing tactics, using misleading ads to push its products onto unsuspecting consumers.

Here is an excellent example Michale Moss again. In his book, he describes Kellogg’s American ad campaign for sugar-laden Frosted Mini-Wheats as a prime example of how food companies have used misleading ads to push their products.

According to Moss, Kellogg’s faced a dilemma with Frosted Mini-Wheats. On the one hand, the company wanted to appeal to children, who apparently wanted dessert for breakfast. On the other hand, Kellogg’s needed to convince parents that the cereal was healthy and could help their children perform better in school.

So to do this, the company devised an ad campaign that sold Frosted Minis as brain food.

Moss describes the TV commercial that aired in early 2008, where a classroom scene showed a teacher losing her train of thought while her students looked weary and tired. One boy in the class comes to the rescue, reciting the exact paragraph and page number they were on before the teacher’s chalk broke.

Then a voice-over makes the point: “A clinical study showed kids who had a filling breakfast of Frosted Mini-Wheats cereal improved their attentiveness by nearly 20 percent. Keeps ’em full. Keeps ’em focused.”

The ad ran widely on TV, the Internet, and various modes of print, including the sides of milk cartons.

Just one problem: the claim wasn’t true.

Moss reveals that the clinical study cited in the ad campaign was commissioned and paid for by Kellogg’s itself, making it suspect from the start.

Even if taken at face value, the study did not support the claim made in the advertising. Half of the children who ate bowls of Frosted Minis showed no improvement on the tests they were given to measure their ability to remember, think, and reason, compared to their ability before eating the cereal. Only one in seven kids got a boost of 18% or more.

The Federal Trade Commission called the ads false or misleading and opened a legal proceeding against Kellogg’s.

“It’s especially important that America’s leading companies are more ‘attentive’ to the truthfulness of their ads and don’t exaggerate the results of tests or research,” the FTC chairman said in a statement. “In the future, the commission will certainly be more attentive to national advertisers.”

It took more than a year for the FTC to issue a decision that barred Kellogg from using the claim, Moss wrote in his book, and four years later, Kellogg agreed to pay $4 million to settle this lawsuit.

But according to the company’s internal survey, the ad dollars did its job: “a resounding 51 percent of the adults surveyed were not just certain that the claim about attentiveness was true; they believed it was true only for Frosted Mini-Wheats. That is, only by dropping that cereal into their shopping carts would their kids get ahead in class.”

This incident highlights the trend of food companies using deceptive marketing tactics to sell their products and the need for increased regulation and accountability to protect consumers from such misleading claims.

I don’t know how to validate this. Because I don’t know where to find any peer-reviewed studies validating this. I searched their website and searched the internet, and I couldn’t find any study that proves Bournvita directly leads to ‘inner strength’ and ‘strong bones’.

But if you follow the star marks on the pack, you’ll reach this:

“Bournvita contains a bundle of nutrients that are known to support in the maintenance of strong bones (Vitamin D, Phosporus), strong muscles (Vitamin D, protein)….”

Basically, companies don’t need to prove their product does the things they claim. As long as they can prove that a certain nutrient (like protein) does a certain thing (like help build strong muscles), and they can prove their product has said nutrient (no matter in what quantity — two serves of Bournvita have <3gm protein), they can claim that their product does what it claims (help build muscle).

So yes, two serves of this drink will give your kid half of their daily Vitamin D, but that will also exhaust more than half their daily added sugar limit.

Healthy or not? You decide.

Like what you see so far?

Get TBT articles in your inbox every Saturday

Let’s zoom out and focus on the big question: do our kids eat what they like, or do they like what they eat?

Research suggests it’s the latter: we tend to learn to like what we eat, rather than the other way around. So when we feed our children ultra-processed foods, we’re essentially shaping their taste preferences. If we feed them candy, they expect more candy.

That is the problem. That’s how this machine works. And thrives.

Which is why I said: Bournvita is NOT the problem. The food environment in which Bournvita exists is the problem.

In a world where regulatory enforcement is weak, where marketers are mad creative, where food companies rarely receive critical coverage from the press, and where nutrition education is not given its due importance, social media users and influencers — like Revant Himatsingka — have taken it upon themselves to expose the truth behind the food we consume.

Their goal is raising consumer awareness, and boy oh boy, are the big brands getting worked up about it.

So what can you do? Simple. Learn to read nutritional labels and make informed choices. Start with our guide to smart food shopping.

The truth is out there — it just takes some effort to get there.

NOTE: How much “added sugar” should you consume in a day?

The exact number is a bit debatable, so here is how I settled on the 25 gm figure.

The ICMR tells you 30 gms of sugar per day. WHO says 50 gms per day okay, but says 25 gms recommended.

Go to FSSAI labelling regulation, where it’s important to make a distinction between ‘total sugar’ and ‘added sugar’ – and they keep changing the guidelines. In one draft, they said 25 gms added sugar as the benchmark, but when industry pushed back, they raised it to 50 gms of added sugar as the daily limit, but didn’t say anything about total sugar.

So after reviewing all this, I have settled on this: 25 gms of ‘added sugar’, and 50 gms of ‘total sugar’. It may not be perfect — leaving that to the scientists to perfect it — but at least it gives me some clarity.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of The Whole Truth or its members. Also, the views or opinions represented herein are for general informational purposes only, and is in no way meant as an evaluation or judgement of any particular product. We accept no responsibility, and shall have no liability, for any loss or damage which may arise from using or relying on the information. Also, the content is not intended to be a substitute for professional advice in any manner.

Click on this to sign up for the truth