How I Forgot to Chew (And Why My Father Ensured I Did)

The most trustworthy source of food and

fitness journalism in the country.

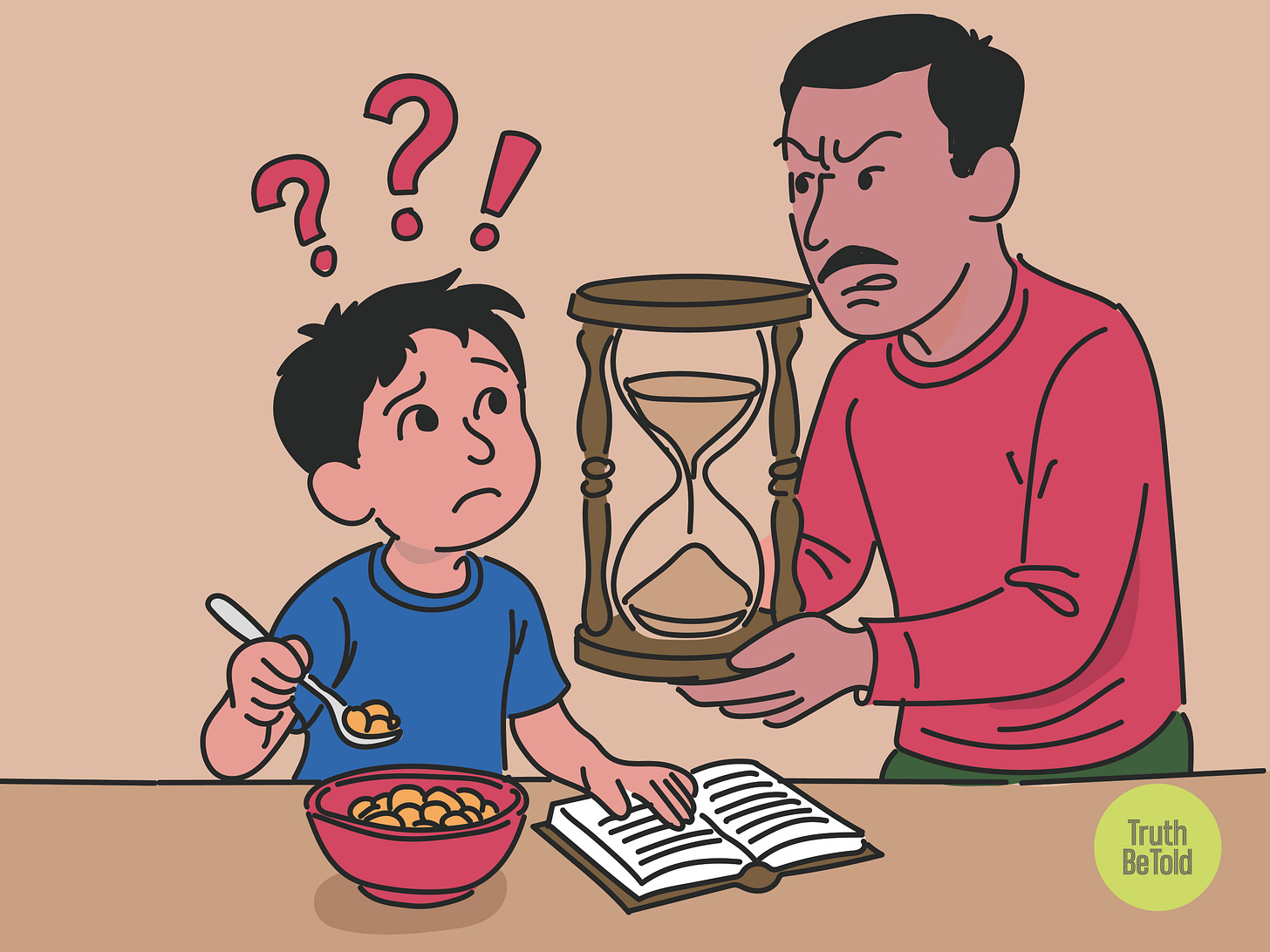

Editor’s note: What does it mean to eat like you’re running out of time? Why does anyone do that? Don’t we know better?

It’s this thing—“knowing”—which through the lens of science is about finding just the right fact somewhere and then doing it. Which frames “knowing” as the problem. But that’s not how life works. As Tanmoy Goswami reveals in this gorgeously moving personal essay, our relationship with food isn’t about willpower or knowledge—it’s about fear, love, and the stories our bodies remember. And why changing how we eat means confronting how we’ve learned to live.

I have admired Tanmoy’s writing for so long, and am so glad that he chose to write for us. He is a lived experience expert and the creator of Sanity, a solo-run, independent, reader-funded mental health storytelling platform with subscribers in over 50 countries. You can connect with him here and here.

PS: Here is a short feedback form to help us understand how we’re doing. Would you please share your thoughts? Link here. For more, you’ve got my email.

— Samarth Bansal (samarth@thewholetruthfoods.com)

My wife would have cheered for Horace Fletcher. My father would have called him names.

Fletcher, a millionaire health reformer in the US in the early-1900s, had a singular mission: teaching Americans how to chew well. Through his own struggles with obesity, he had come to suspect that swallowing food too quickly was to blame for all manner of illnesses. He believed that digestion happened in the mouth, not in the stomach. Ergo: If you didn’t chew your food thoroughly, it would pile up in your intestines and block you up.

He also claimed that citizens extracting the maximum energy out of every morsel by chewing it to a mush — he once chewed a green onion 722 times over a full 12 minutes — would fuel a prosperous economy. Among Fletcher’s fans were Arthur Conan Doyle and US President Herbert Hoover. The novelist Upton Sinclair even coined a nifty slogan for Fletcherism: “Nature will castigate those who don’t masticate.”

Odds are, you too grew up with a dietary rule apocryphally credited to Fletcher: You must chew every bite 32 times (once for each tooth).

My wife, born to a vegetarian Kannadiga family based in Delhi, inherited this rule from her strict maternal grandfather. She swears that slowly is the only human-like way to eat and is constantly dismayed that I, a carnivorous Bengali from the small steel town of Durgapur, have no regard or talent for this life skill. She likes savouring her food. I want to get it out of the way.

Once at a fish market in Sweden, I swallowed a smelly jar of herring without stopping for air and nearly choked. At a small fish-and-chips joint in England, I ate a giant beer-battered haddock and half a kilo of vinegar fries so fast that I felt like fainting. Just last week at an Andhra restaurant in Mysuru, I put away four refills of rice and rasam before my brain could register that my belly was painfully distended. My wife had no idea that I had to crawl to the loo and vomit so I could breathe again.

Don’t get me wrong: I do understand the value of a good chew. I have lived my entire life with serious mental health conditions, accompanied by assorted bowel and weight issues. I am aware that people with healthy weight tend to be more efficient chewers. I also know that eating slowly could help me control my portions by stimulating the production of “fullness hormones”, make me feel more in control, and curb my perennially high stress levels.

I have another strong motivation to slow down: I want to model healthy mastication before our 7-year-old.

I just don’t know how to.

“You’ll always come last”

As a child, I was a meticulous chewer. I’d start eating an hour before everyone else and finish an hour after. Books were responsible for my sloth. I wouldn’t eat without a Tintin or Feluda open in front of me. My mother had to wait inordinately for me to finish my cycle of chewing every bite cow-like – licking my fingers – sipping water – flipping the page – repeat, so she could clean up the mess of fossilised drumsticks and crusty gravy I left in a circle around my plate on the floor.

Maa, a nurse, indulged my inefficiency. But my father, a worker in the local steel plant, had no patience for it.

“How can anyone eat so slowly?” he’d bellow every mealtime. “You will never be able to catch a bus or train. All your friends will move on without you. You will always come last at everything. HAATH CHAALA. Move your hand. TARATARI KHAA. Eat faster.”

Eating with Baba is a dizzying experience. He is loud. And relentless. He slurps great quantities of bhaat and aaloo poshto and maacher shorshe while simultaneously commenting on the lack of salt in this and the excessive turmeric in that, noisily licking his fingers and burping mid-meal, ladling a heap of leftover pumpkin meant for the dogs and reprimanding us for wasting food while complaining that he has overeaten, and before you know it he is already gargling with great torrents of water and spitting out every grain of food from his oral cavity with such force that you’d think he was going to burst a vein. His eating isn’t pretty. But he eats with all his being.

When I was a child, his being was also frequently possessed with violent rage. Failing to follow his orders had terrifying consequences. His sudden explosions over seemingly trivial matters used to confuse me, but I learned early that safety lay in unquestioning obedience.

So I began to truncate my luxuriant meals. I figured out that delivering every mouthful straight from my fingers to my oesophagus, bypassing my teeth altogether, was a great hack to eat at 2x speed.

I found help in my lifelong aphthous ulcers. Every couple of weeks, my mouth erupts in fiery red boils that make chewing impossible. When I was small, a dentist had pronounced: “This boy seems stressed.”

Of course, “stress” was an absurd diagnosis for a kid in the small-town India of the 80s. But happily, the ulcers gave me further practice of eating without chewing.

When speed is not a choice

I left home for college at 18. I am 42 now, and my father just turned 70. Maybe someday I will tell you the story of how he transformed himself into the kindest, gentlest old man I know. I am proud of this version of Baba — but I resent that his scowling avatar who continues to live inside my head still forces me to bolt down whatever’s in front of me.

Why was it so important for Baba that I chose speed over pleasure? It has taken me years of chewing on it in therapy (sorry, I had to write that at least once) and a funeral in the family to get a clue.

My parents were both born in impoverished families in rural Bengal. But they formed completely different relationships with food.

The eldest of five siblings, Maa became her family’s primary breadwinner when she was a teenager. She went to nursing school and spent her training years on a diet of barley, rice, and potatoes because that’s all she could afford. My father says the deprivation shrunk her stomach permanently, which is why she “eats like a bird”.

Baba, the middle one of six children, grew up internalising that food is a lottery. A couple of years ago, his elder brother died of liver disease. At his funeral, I told his younger brother how shocked I was to hear about Bodo Jethu’s illness.

“I wasn’t,” Kaka said. “I mean he and your father often didn’t get to eat two proper meals a day…”

You eat till your stomach hurts, and you eat as fast as you can, because you cannot trust food to last.

In his 20s, Baba, once a promising student, was forced to join the steel plant after politics cost him a job at the town’s telephone exchange. For the rest of his working life, he woke up at 4.30 every morning, helped Maa make lunch before she left for her morning shift, cleaned the house, woke me up and readied me for school. He had 5 minutes to finish his breakfast of ruti-tarkari and a saucer of tea, because a cup would take too long to cool. Akashvani Kolkata’s morning news served as his pacesetter so he wouldn’t miss his 6:45 am bus.

He would come home by 5 pm every afternoon — except on days when he returned early with a burnt finger or smashed toe from an industrial accident. I was equally terrified and intrigued about where he worked, but he refused to share too many details about the plant or take me there. Finally, a few years before his retirement, when I had started working myself, he invited me to come see where he had spent three decades of his life.

Baba’s workplace was atop a giant furnace. His job was to shove coal into the belly of the furnace where fire burned at 1,200 degrees. The scale of the machinery all around, the heat, the noise, the feeling that real workers were doing real work in this inferno where one small error could turn deadly, unlike our generation struggling with cubicle fever and carpal tunnel, overwhelmed me.

One image has stayed with me years later. My father and his colleagues carried uncooked rice and daal from home. At lunchtime, they placed their tiffin carriers on top of the giant metal lid that covered the furnace’s mouth. The food inside got cooked in minutes. It wasn’t a setting conducive to leisurely meals.

This was the muscle memory of rapid eating that Baba sought to transfer onto me. He wasn’t angry that his child was a slow eater. He was scared for him. He didn’t want to punish him. He was trying to prepare him for a world where slowness was not an option.

A father’s guilt

A man changes when the fear of turning into his father grows bigger than the shadow of the father himself. All the gastrointestinal science in the world couldn’t make me reform my chewing. I am hoping being a dad myself will.

You see, my son doesn’t find me stuffing my face grotesque. To him, it is my superpower. He wants to be like me. Every time I yell at him for nibbling at his breakfast on school mornings — “you’ll miss assembly, AGAIN” — he looks at me with the expression of a child who believes he is a disappointment. I feel ashamed. I want this cycle to end with me.

Clinical labels, such as “eating disorders”, tend to shrink our vast, complicated humanity to a checkbox of symptoms. After a lifetime of wrestling with a morbid mind and broken body, I am learning to accept that looking at my life through the lens of generationally transmitted suffering doesn’t account enough for my personal privilege. I hope someday my privilege will help me move on from my family’s narrative of scarcity to a feeling of abundance and gratitude.

That’s the inheritance I want to leave for my son. He will discover soon enough that life is an endurance sport. I want him to know that eating doesn’t have to be.

When I posted on Instagram that I was working on this piece, many people reached out to me with their own stories. Priyanka Bajaria, a psychotherapist and clinical supervisor, was one of them. Priyanka’s ancestors were migrants. Her memories of food are marked with the ideas of “control, safety, and sustenance, and a deeper yearning for stability in the face of the uncertainty of pain.” Her message made me smile with self-recognition, and I had to read it out aloud to my wife.

“Rushed, distracted eating often reflects a nervous system stuck in fight-or-flight, an inability to be with oneself,” Priyanka said. “These patterns frequently emerge in couples therapy, where food can become a microcosm of a relationship’s emotional landscape. A partner who rushes through meals while another savours each bite may not just be a matter of preference but a reflection of deeper relational dynamics, attachment styles, past experiences of scarcity or abundance, or unconscious messages about care. When couples begin to reflect on how they eat together, they often uncover patterns of connection, neglect, or discord that play out beyond the table.”

Every time I find myself rampaging through dinner these days, I start thinking about that last sentence. It acts as a speed breaker.

Priyanka’s wish is that the food industry talk more about the emotional core of eating and not just microbiomes and elimination diets. And, contrary to Horace Fletcher, she wants us to remember that food isn’t just fuel.

“When we start paying attention to how we eat, we may find that the real nourishment we seek has little to do with food at all.”

Just Dropped

A masterclass on managing caffeine: How much coffee is too much?

Are energy drinks bad for you?

Does refrigeration kill nutrition?

Here’s how I got my cholesterol levels down

How to eat: Healthy eating habits

How to manage alcohol consumption and fitness?

My autoimmune journey: I lost all body hair, but gained inner strength