Nutrition science is so confusing. That’s okay!

The story of how scientists tried to agree on what can constitute “healthy and nutritious food,” and how they just couldn't. What does that mean for your lunch?

The most trustworthy source of food and

fitness journalism in the country.

Hi there! Samarth Bansal here, your Editor. I am writing today’s edition that deals with a somewhat meta question about knowledge and ignorance around health and nutrition: is figuring out what to eat really complex?

In November 2015, physician-turned-journalist James Hamblin attended a gathering of 25 world-renowned nutrition scientists, organised by David Katz, director of the Yale-Griffin Prevention Research Center, and Walter Willett, chair of the Department of Nutrition at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

These experts united with a clear objective: to dispel the notion that nutrition science is chaotic and to converge on shared principles regarding food and health that could benefit society.

Each scientist made a case for why their dietary approach was the optimal one for health. The perspectives were quite diverse: Among them were T. Colin Campbell, a leading figure in the modern vegan movement; Stanley Boyd Eaton, co-creator of the ‘Paleo diet’; and Antonia Trichopoulou, who brought the ‘Mediterranean Diet’ to global prominence.

They heard each other. Then they decided to sit down and ‘find common ground’. It started with a simple proposition that Hamblin — the only journalist in the room — thought would be the least controversial: “Can we say that everyone should eat vegetables?”

Hamblin was asked not to quote anyone directly to encourage free brainstorming and open dialogue, but in his book, If Our Bodies Could Talk, he recounts the conversation as follows

Most nodded. Then someone said, well, what kinds of vegetables? Cooked or raw?

Right, I was just thinking that, because we can’t have people eating only white potatoes. Those are pure starch.

Are French fries and ketchup vegetables?

I think people know that when we say vegetables, we don’t mean to eat purely French fries.

Do they? The federal school lunch program says they are.

Lots of talking over one another.

Well, what if we say to eat a variety of different-colored vegetables?

I don’t think that’s supported by evidence.

Does it have to be?

YES.

They could still cover the colorful vegetables in salt, and that wouldn’t be good.

Or deep-fry them.

Should we say raw?

No! We can’t neglect the importance of flavor!

And cultural tradition.

What about seasonality? We can’t have everyone eating avocados all year round.

“After the first hour, we had arrived at no consensus on whether it could be said that people should eat vegetables,” Hamblin wrote.

This rattled me a bit. Think about it. The world’s leading scientists, who have dedicated their lives to studying nutrition, couldn’t agree on how to recommend eating vegetables.

Why?

Hamblin explains:

“Over the next four hours, it became clear why this sort of consensus statement does not exist. Every one of the twenty-five scientists in the room did, very clearly, agree that people should eat vegetables. And fruits, nuts, seeds, and legumes. They all agreed that this should be the basis of everyone’s diets. There should be variety, and there should not be excessive “processing” of the foods.

The devil was in how to say this. They stayed until midnight that day in Boston, trying to figure it out.”

That’s the critical point here: reaching a consensus on nutrition isn’t solely about agreeing on what to eat; it’s about finding the right way to communicate complex ideas effectively and universally.

Which requires understanding context, anticipating how people might interpret the information, and considering the potential ramifications of how it’s conveyed.

Fair enough. But where does this leave the average person? The scientists themselves – in a moment of collective self-awareness – recognised that their inability to present a unified front leads to significant societal issues.

Nutrition scientists worry about the interpretation of the message.

As Hambin writes:

When people sense the absence of a single established consensus on nutrition, this invites them to see every diet trend as equally valid. It gives credence to whatever the latest news story suggests, or whatever the Kardashians are doing, or to whoever is selling the latest book about how carbs/fat/gluten are “toxic.”

And then this absence of agreement becomes the ultimate weapon for the powers-that-be to exploit this uncertainty. You know the classic trope: “experts disagree!”

This leads to the cultivation of ‘active ignorance’ — one of the biggest obstacles to a healthier society. He writes:

Experts can and will continue to disagree on how to interpret bodies of evidence; this is a foundational element of science. It means the process is working like it’s supposed to. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t consensus about many of the tenets of nutrition.

Hamblin describes this as a “tactic of demagogues to make people believe that no one knows anything—so you might as well believe their absurd idea.”

Experts disagree on the same topic.

Let’s make the problem clearer. Many people confuse ignorance as simply the lack of knowledge. Nope—that’s a relatively easy problem to solve: providing more facts.

Ignorance is actually the outcome of deliberate cultivation, says Stanford professor Robert Proctor. It’s spread through tactics like marketing and rumour, which spread more widely than more informed, wise words. From Hamblin’s book:

The classic example of purposeful ignorance is that created by the tobacco industry. Ever since tobacco was clearly proven to cause lung cancer in the 1960s, the industry has attempted to cultivate doubt in science itself. It cannot refute the facts of cigarettes, so it turned the public opinion against knowledge. Can anything really be known?

The strategy was brilliant. Proctor calls it “alternative causation,” or simply, “experts disagree.” Tobacco companies didn’t have to disprove the fact that smoking causes cancer; all they had to do was imply that there are “experts” on “both sides” of a “debate” on the subject. And then righteously say that everyone is entitled to their belief. The tactic was so effective that it bought the industry decades to profit while reasonable people were uncertain if cigarettes caused cancer.

As Proctor put it, “The industry knew that a third of all cancers were caused by cigarettes, so they made these campaigns that would say experts are always blaming something—brussels sprouts, sex, pollution. Next week it’ll be something else.”

This pattern—we all know—is so rampant in health information. Ignorance, then, is as much an enemy of a healthier world as refined sugar. We must resist the cultivation of ignorance—in ourselves, and our society.

🥗Share this with that friend who keeps changing their diet.

I wanted to talk about this because it is sometimes helpful to make the nature of the problem more clear. So we know what we are dealing with.

But what to do? How to resolve this problem?

Here are some ideas.

1) Focus on commonalities: First and foremost, let’s be clear: don’t buy into the narrative that nutrition science is in a complete state of chaos. Yes, it can be complex. It’s full of unknowns. Our bodies are unique: what works wonders for one person might not do the same for someone else.

But here’s the crux: even those who hotly debate topics like ‘how many eggs should we eat in a day’ will find, upon sitting down and comparing notes, that they agree on a lot more than they disagree. It’s just that we tend to fight tooth and nail over the differences and brush the commonalities under the carpet.

2) Basics matter: Everyone agrees that whole foods are good for you and excessive sugar intake is bad. Vegetables are universally acclaimed: eat seasonal, eat local, and have a colourful plate. More fibre is great. Eat varied food groups, depending on your dietary preferences: fruits, eggs, meats, lentils, dairy. There’s a general nod towards the benefits of more protein. Eating in moderation is always advised. Portion control helps. Eating slowly is better.

There is little debate on these basics. Bring them into the spotlight. If you stick to these, you’re unlikely to stray far from the mark.

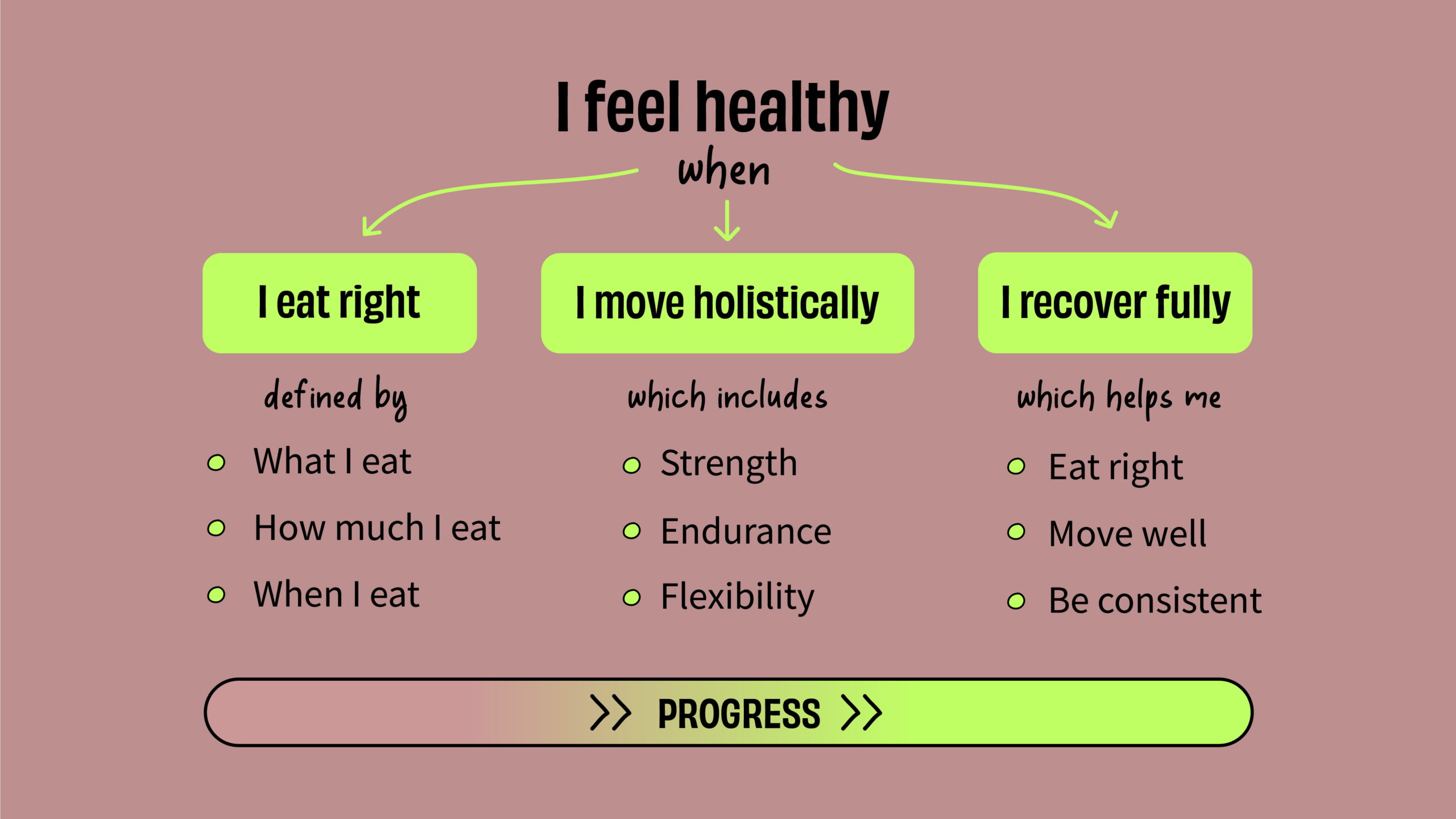

3) Build your food philosophy: Getting your head around health isn’t just about digesting new facts; it’s about how you interpret and think about these facts.

You need your own set of rules, your personal food philosophy, so when a new bit of info pops up, you can assess its significance: is this just a fascinating tidbit for intellectual curiosity (for me, it’s super fun to nerd out on these details), or does it have a real, practical impact on your life? This helps you size up how much weight to give to new studies or those pesky conflicting reports.

This process involves introspection and critical thinking. Reflect on everything you’ve read and experienced in the realm of nutrition and health. Maybe spare half an hour to jot down these thoughts. (Getting it down on paper often offers razor-sharp clarity.)

We published ours right in week one of launching this newsletter. You can read it here.

4) Self-experimentation and knowing it’s okay to not know: One of the fundamental truths of science, nutrition included, is that uncertainty is part of its nature. We must accept that there are things we simply can’t know for sure – at least not yet. What we ‘know’ today might be revised tomorrow, and that’s perfectly okay.

4) Self-experimentation and knowing it’s okay to not know: One of the fundamental truths of science, nutrition included, is that uncertainty is part of its nature. We must accept that there are things we simply can’t know for sure – at least not yet. What we ‘know’ today might be revised tomorrow, and that’s perfectly okay.

The best bet, then, is to build on the general principles and see what works for you. Try. Experiment. Learn to listen to your body. Observe the cues. And over time, you will figure out what’s best for you—and what you can sustain.

Think of these suggestions as another habit—the habit of thought. Given the world we live in, it’s important to build one so you don’t spiral into anxiety. Or you’ll be stuck in the vicious cycle where wanting to learn facts on health will give you anxiety, and then anxiety will hurt all your efforts to become healthy.

And another habit for you: Share all our pieces with your family 🙂