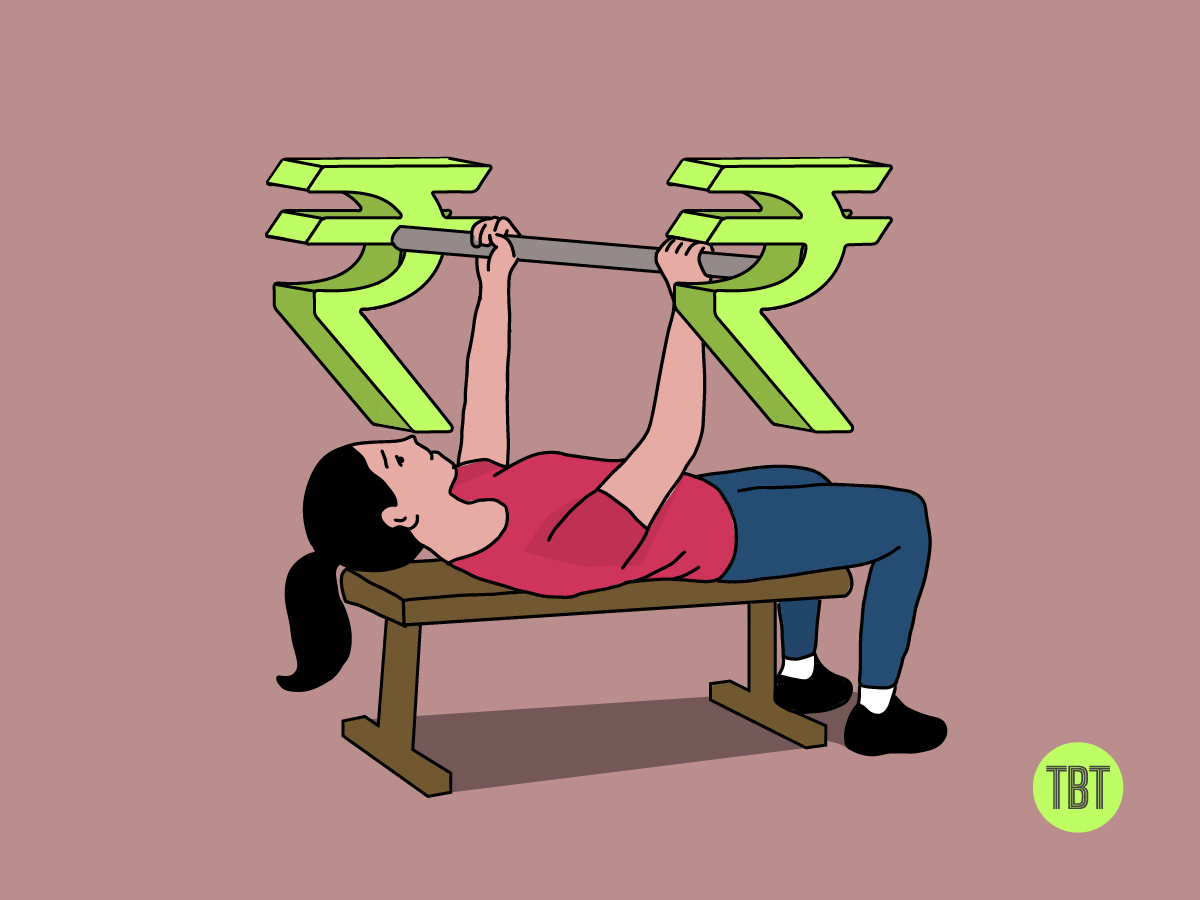

How much do you really need to invest in fitness?

The most trustworthy source of food and

fitness journalism in the country.

Editor’s note: Over the last nine months since I moved to Bombay, I am a bit—a bit too much—bummed by how expensive fitness seems in the Bandra-Juhu microverse. The PT charges are nuts, meal subscriptions cost a bomb, and the optionality of optimising for workouts is—depending on my mood—super impressive or just comically absurd. Just too much.

So how do we navigate this can’t-really-complain first-world-type problem? Does fitness have to be this expensive?

In today’s issue, Lavanya Mohan writes about how she approaches this dilemma. She is a CA by qualification (i.e. good with money things) and currently heads Social Media at ACKO. And she is a writer, and her work has appeared in The Hindu, Verve India, The News Minute among other places. You can find her at @lavsmohan and read more of her writing at The Ledger.

Lavanya shares her framework to think through this problem. I hope this serves as a valuable guide for your own intentional fitness journey.

PS: Here is a short feedback form to help us understand how we’re doing. From day one, TBT has been published in service of our readers—and I want to ensure we’re on the right track. Would you please share your thoughts? Link here. Thank you!

— Samarth Bansal (samarth@thewholetruthfoods.com)

At some point in the last decade, wellness became an industry—a booming, unavoidable, and relentlessly marketed one. The days when “healthy” meant a walk in the morning and two rotis for dinner are long gone.

The modern fitness economy is built on the idea that being “healthy” is more than just maintaining a reasonable BMI. It needs to be optimised for strength, longevity, mobility, and calm.

Sure, you’re working out, but are you tracking it? You might be going to a gym, but is it the kind with the latest squatting equipment and cryotherapy? You might be having protein, but are you supplementing it with creatine, collagen and multivitamins?

These additions aren’t inherently bad, but for most of us who are beginners and are looking to get started with a fitness routine, they’re not essential. If you get enough movement, eat a reasonable amount of protein and sleep well, your health goals are likely being met. (Read this to brush up on the fundamentals.)

But the industry markets these extras as non-negotiables—not as optional optimisations for those who’ve progressed considerably in their fitness journey.

This blurs the line between helpful and hype. This is where the spending spiral begins. And financial health can possibly go for a toss.

The point of this piece isn’t to tell you not to spend on your health—after all, I’m probably a prime contributor to the wellness industry myself. I go to a gym with decent equipment (no cryotherapy, but not a budget gym either). I have a trainer who does one-on-one sessions with me 4 times a week because I’ve just started learning how to lift. I take a small cocktail of supplements: Vitamin D and Magnesium.

The point is to make a case to make health spending intentional—and safeguard ourselves from the extractive forces of wellness consumerism.

But first, let me show you how I have seen things changing.

Too many choices. So much confusion.

My own journey into this intermediate category of fitness began 18 years ago. I was entering my twenties grossly overweight and diagnosed with PCOD. My paranoid, diabetic and very exercise-conscious father decided enough was enough and packed me off to the gym. I was pursuing my Chartered Accountancy at the time—a course that’s as stressful as it is lonely—so I found myself at the gym because I had nothing better to do.

As a result, I lost weight and found a lifelong habit.

This was also when my spending on health began. My father’s early diagnosis of diabetes had him (slightly) obsessed with ensuring that his children don’t have to deal with it. My parents’ generally keen surveillance of the family expenses more or less shut down when it came to good health.

The message was clear: spending on health is worth it. This is a mantra I (and thousands more) continue to carry.

Except in 2007, when I started going to the gym, there were barely any avenues for spending. Most gyms were pretty standard and cost less than ₹1,000/- a month if you got an annual membership on offer. There were no smartwatches, no protein powders or supplements. Gym clothes and shoes were restricted to the usual sportswear brands.

The beginner fitness enthusiast today, on the other hand, oof.

Which gym do they go to: the one with no cardio machines, the one that insists that the only skill you need is learning how to scale walls or the one with pilates lessons?

Which protein powder do they choose: whey or vegan?

Which tracker do they choose: the watch, the ring, the band or the glucose monitor?

The choice overload is intense and never-ending.

I was lucky enough to escape this cycle because I started my fitness journey in the paleolithic era, but I see this happening all the time with friends and family who spend weeks researching gadgets, protein powders and supplements all at once when they should be focusing on figuring out how they can simply get started.

And then they started buying. And buying. And buying. Only to end up with unused rings, protein powder that was used in three shakes tops and crystalised bottles of collagen, because buying felt like progress in itself. Like buying the gear would magically create the habit or make you fitter. But without a plan or an already existing habit, all it creates is clutter—and perhaps guilt. The sort that stares at you from your drawers and cupboards, reminding you of the goals you abandoned and the holes you created in your bank account.

And that’s the thing: unlike most consumer spending, fitness doesn’t feel frivolous. But when does optimisation turn into overconsumption?

Fitness. Self-worth. Identity.

Why is it so easy for us to spend on health? Because fitness is more than just an expense—it’s an identity.

We aren’t just gym-goers; we’re lifters, runners, cyclists, yogis. We don’t just eat—we meal prep, count macros, and biohack. And once something is part of your identity, spending on it doesn’t feel like a choice. It feels essential.

That’s why wellness spending is so insidious—it’s never just about the product. It’s about who you are when you buy it.

And as long as identity remains a selling point, brands will continue to convince us that a healthier, stronger, better version of ourselves is just one more purchase away.

Make no mistake: there’s nothing wrong with spending on, nay, investing in your health. But there’s a difference between what you need and what’s been marketed as necessary.

To me, it comes down to intent and impact.

Does this support a real, personal goal of mine (intent), and does it make a measurable difference in how I move, feel, and recover (impact) — or is it just shiny and all over my Instagram feed?

It’s easy to confuse the two, especially in a space where everything is labeled “science-backed,” “clean,” or “essential.” But not everything that fits your feed fits your life.

Wellness shouldn’t have to be an endless capitalist loop where the only way to be ‘better’ is to buy more.

Three questions. For intentionality.

As someone who’s equally interested in both health and personal finance, this is a battle I fight every single day. My approach towards health-related expenses involves asking myself three questions.

One: On whose recommendation am I buying this?

This one takes on modern wellness’s great bane: social media. Fitness, once a private pursuit, is now an everyday performance.

With influencers showing their workouts, their abs, their protein shakes, and activewear on an hourly basis, it’s easy to get swayed into believing that the products they’re shilling will enable us to become them.

This isn’t to say that influencers don’t have a positive impact on fitness or introduce us to newer products in the market. It’s to say that they’ve far more incentive to push something—it’s to say that they’re being paid to push products, and they gain from your buying.

I’ve limited my buying—whether it’s supplements, activewear or gym gear—to the recommendations of my trainer or friends and colleagues who are also gym-goers. If a recommendation is coming my way from those who are genuinely interested in my progress, then it’s likely worth the money.

Two: How is this going to make me healthier?

I need to be able to articulate the effect of the product on my health. What’s it going to do for me? Protein powder, for example, is an easy one. I’m a vegetarian with a protein-lacking diet. I need the powder to meet my goals. I’ve started lifting heavy, and creatine helps me channel energy more efficiently.

But I’ve never been able to articulate why I need a sleep tracker. I know I sleep for 7 hours. And I don’t know what I’ll do with the metric. And when I can’t spell out why it’ll make me healthier, I know I shouldn’t buy it.

Three: Is there a cheaper—but equally effective—way to do this?

Finally, I search for alternatives, but only if the product is equipment and not edible. I strongly believe that while activewear, shoes and equipment (like bands, straps and grips) are more or less standard in their make, what you put inside your body cannot be debated on the basis of price. Quality ingredients cost more.

This isn’t to say that the most expensive brand has the best quality ingredients, but that you’re not doing yourself any favours by opting for a brand just because it’s cheaper. For non-edible fitness equipment, there’s almost always a cheaper but similar quality alternative.

How much is too much?

That’s it. Three questions. That’s my framework for making sure that I’m spending on my fitness — and not indulging in FOMO.

The wellness industry thrives on making you feel like there’s always something more to buy, some edge you’re missing out on. But the truth is, the basics—movement, strength, nutrition, sleep—haven’t changed.

And while physical health is always worth pursuing, it shouldn’t come at the cost of your financial health. I try to stay within spending 10% of my monthly income on wellness because that feels sustainable to me. If you’re just starting out, I wouldn’t recommend spending more than 5% to 8%.

This is a number that’s derived from the 50-30-20 budgeting rule, where 50% goes to your bare necessities (rent, utilities, groceries, internet), 20% goes to savings, and 30% goes to wants (going out, Netflix and gym).

Anything beyond this limit should require serious second thought.

There are a hundred different ways to stay active and enable your body to be the best it can be– without the frills. Understanding what you actually need will go a long way in ensuring it’s not just your body that’s fit but your bank account too.