Longevity secrets: What I learned about preventing chronic diseases

Master healthy aging with tips to fight chronic diseases

The most trustworthy source of food and

fitness journalism in the country.

Editors note : Hey there! Shantanu Kishwar read the new book “Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity” by Peter Attia and shares what he learnt about four chronic diseases: metabolic disorders (like diabetes), heart disease, cancer, and neurodegenerative diseases (like Alzheimer’s).

Just a heads up: Shantanu isn’t a medical expert, just a freelance writer who found these insights interesting from one book. He also works at the WageIndicator Foundation. You can follow him on Twitter and subscribe to Multitudes, his newsletter. But if you’re dealing with any health issues, always wise to have a chat with a real medical pro. Stay smart and take care!

Ill health was my steady companion while growing up. At 17, I weighed around 95 kilos, couldn’t run more than a few hundred metres at a time, and continuously felt odd aches and pains around my body.

I am 27 now, and having spent the last decade trying to outrun my fat childhood, I am largely healthy at the moment: my BMI is well-under control, my last health check revealed nothing of concern, and slowly but surely, my exercise capacity is growing.

As good as things feel now, though, I know in the back of my mind it won’t stay this way forever.

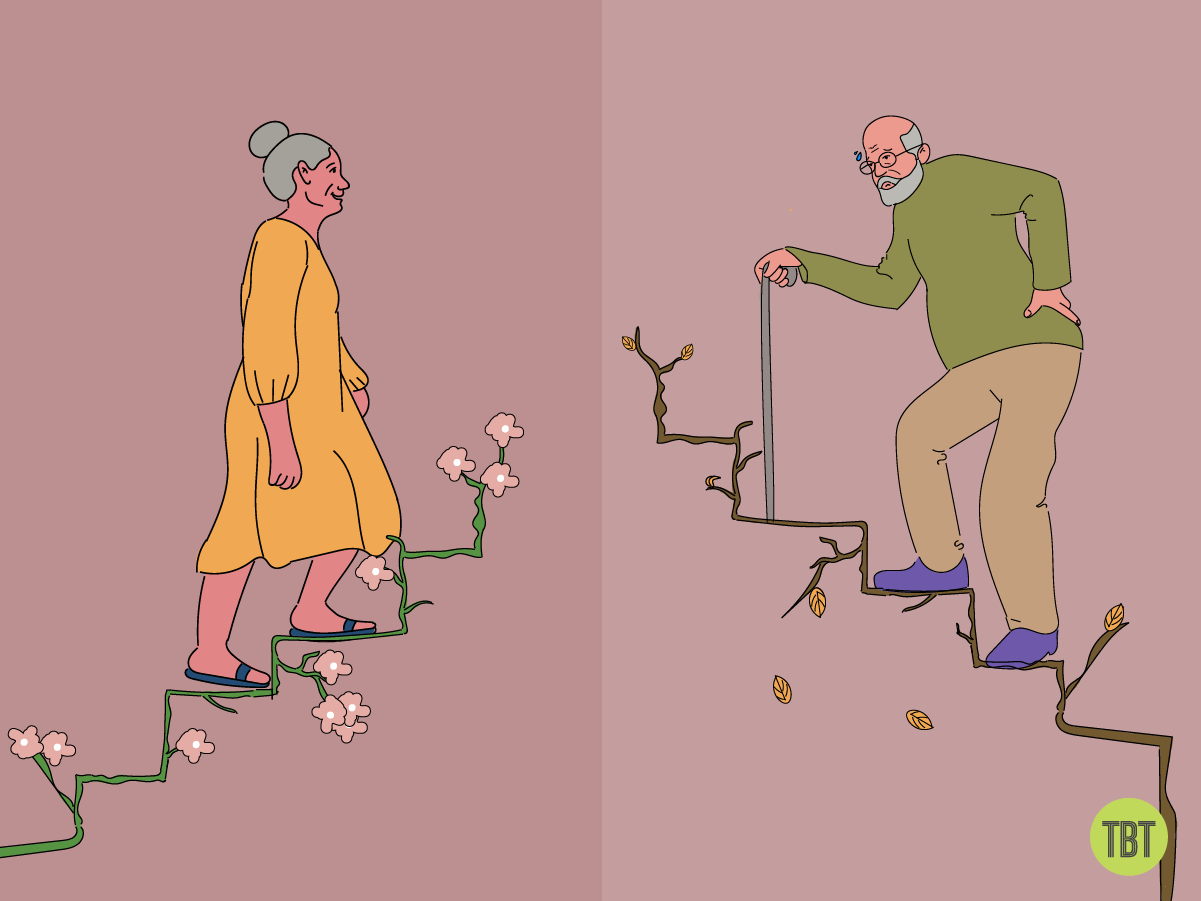

I’ve seen the restrictions old age may impose while spending time with older adults: a friend’s grandmother took six attempts to get out of a chair; my own grandfather couldn’t walk without assistance for the last two decades of his life because a stroke partly paralysed him; the life of a close family friend—once full of literature and art— shrunk and ended because of Parkinson’s.

These sights scared me, so I’ve spent the last year trying to understand and minimise the chances of them becoming my fate.

In this journey, I’ve repeatedly turned to Peter Attia, a physician with a difference. Where modern medicine has focussed on extending lifespan (how long you live), Attia focuses on improving healthspan (how long you’re able to live well).

Healthspan vs lifespan

It might seem like there’s a small difference between the two, but the paths to these fates diverge widely. The healthspan path sets clearly defined goals that may be decades away, like being strong enough to lift a grandchild or trek annually through the Himalayas, and works towards them every day. In my attempts to go down this path, Attia’s insights have been invaluable.

In March, he condensed his knowledge of the science and art of longevity in his book Outlive, which offered me a structure and direction for my long-term fitness efforts.

The book sheds light on four chronic conditions that modern medicine has failed to effectively address: metabolic disorders (like type 2 diabetes), heart disease, cancer, and neurodegenerative diseases (such as Alzheimer’s).

These four chronic diseases matter. Chances are that you know people affected by one or more of them. You might be afflicted by them yourself; if not today, then likely in the future. That’s what today’s piece is about. Think of what follows as my notes: what I’ve learnt so far and how it’s shaping my thoughts and actions.

I. Metabolic Disorder

As an overweight kid in North India, aunties often called me “healthy” while criticising my thin friends for not looking as well-fed. Never mind that at 17, I exhibited one of the five symptoms of metabolic dysfunction, which concerns how your body handles carbohydrates.

Though I wasn’t tested for the other four—high blood pressure, high triglycerides, low HDL cholesterol, and elevated fasting glucose—it would be safe to say I was anything but “healthy”.

But what was unhealthy about my metabolism in the first place?

Metabolism is the process by which your body breaks down food and water into compounds that make your organs function, so it’s pretty damn important.

Part of what you eat will have carbs, and the decision of what to do with these carbs is made by insulin. It either converts them into glucose that flows in your blood or glycogen stored in your liver and skeletal muscles. Any excess gets converted to fat.

This fat isn’t harmful by default; fat stored under your skin (subcutaneous fat) is like a healthy reserve for a rainy day. But when these cells are full, you’re in trouble. The fat starts lining your muscles, hampering their ability to absorb glucose for regular functioning. It can also coat your organs, similarly straining them.

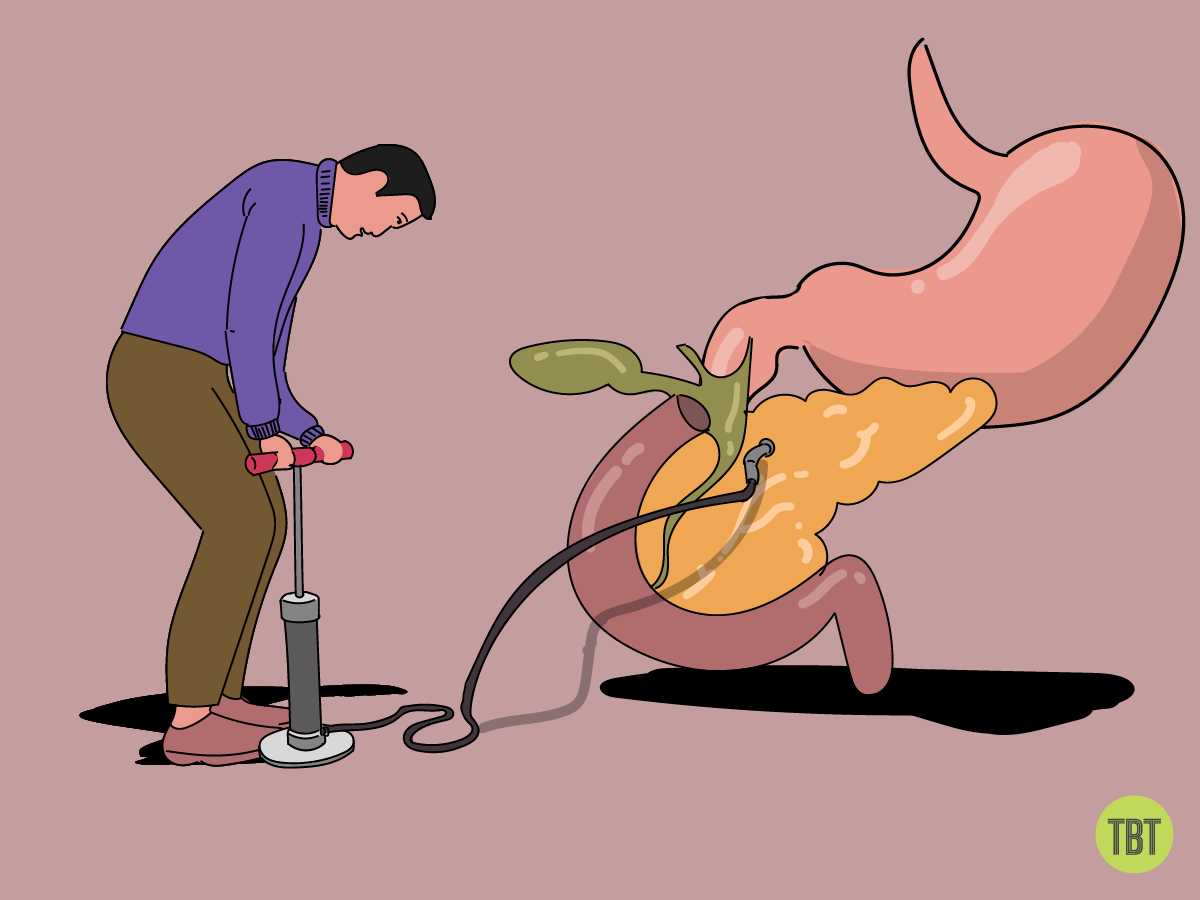

The more glucose in your blood, the more insulin needed to store it. Attia compares it to blowing a balloon; it’s quite easy to initially store air (glucose) in a balloon (your cells). Eventually, you’ll need to pump harder (produce more insulin) to do so.

Trying to produce more insulin

But there’s a limit to this. Soon, your cells will become resistant to insulin, and your blood glucose levels will stay elevated.

This is basic biology.

At this point, you’re at risk for a few different things.

The visceral fat can cause non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, harming your liver’s ability to function in the same way that excessive alcohol consumption can.

Fat deposits around your pancreas limit its ability to produce insulin, triggering a vicious spiral of poor glucose metabolism. The elevated blood glucose levels put you at risk of type 2 diabetes, which itself is associated with an increased risk of cancer (up to twelvefold), Alzheimer’s (fivefold), and cardiovascular disease (almost sixfold).

Which is why preventing metabolic disorders is the cornerstone of Attia’s approach to longevity.

My takeaway: Metabolic disorder seems both easy to get and avoid, at least given my current health status. By being vigilant about what I’m eating and how much I’m exercising, I can keep my glucose levels low and stable. But it’s easy to fall off the rails in a world full of carbs and designed for sedentary living.

Bi-annual Hba1c tests can help me track this, and if I really want to nerd out, there are always continuous glucose monitors to watch my levels in real-time.

📃 Remind someone to check their glucose levels

II. Cardiovascular disease

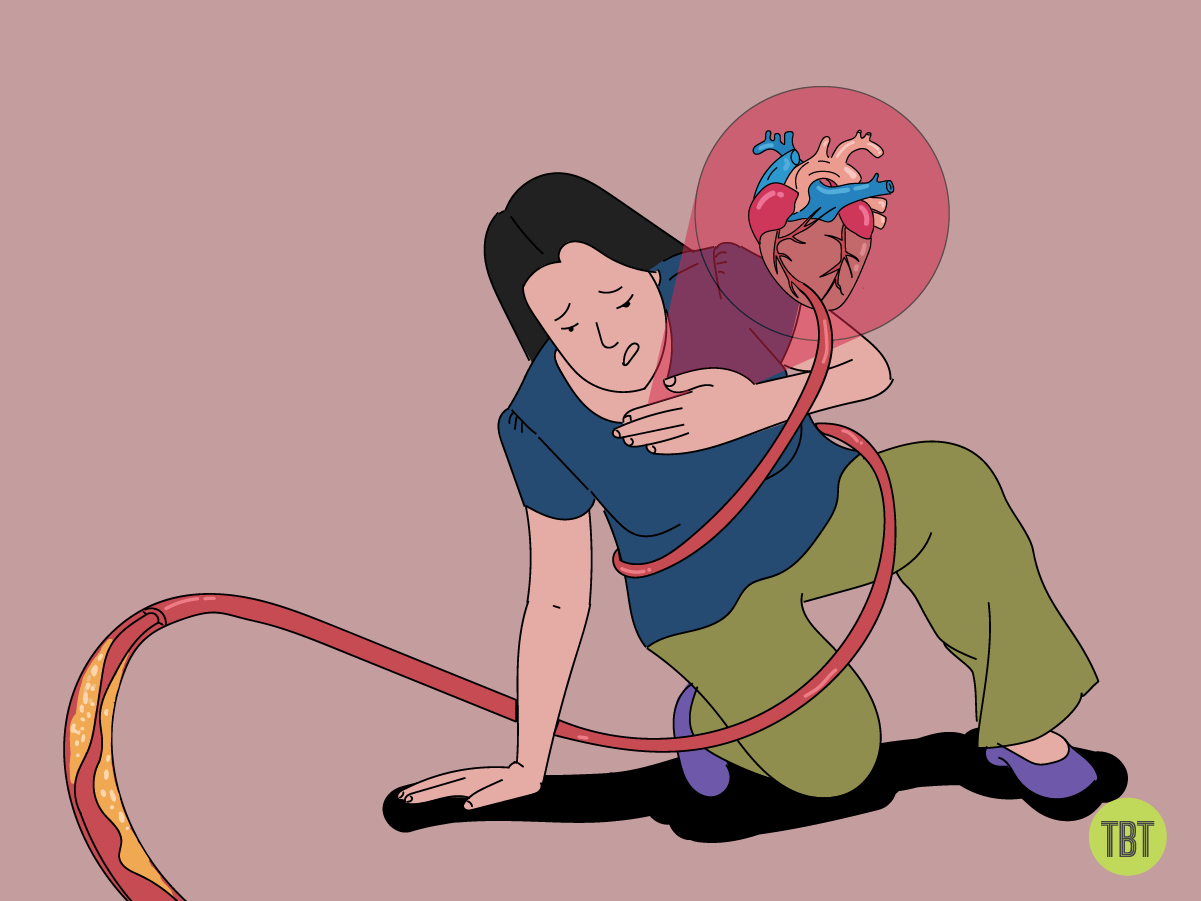

Heart disease is insidious because it develops quietly but emerges suddenly. People can look perfectly healthy, only for a sudden heart attack to bring their cardiovascular disease to light.

This doesn’t solely afflict the old: 50% of heart attacks amongst Indian men occur under 50, and 25% under 40.

Attia blames the high incidence of heart disease on modern medicine’s tendency to wait for people to develop high cholesterol and blocked arteries. These blockages are calcium deposits along blood vessel walls, which can be tested with CT scans.

At the age of 36, Attia had a calcium score of 6. Because severely diseased individuals have scores of over 1,000, conventional medicine wouldn’t worry about his results. In doing so, though, it would ignore that he had more calcium than 75-90% of people his age.

He may have been low-risk in the short term but was well on his way to being high-risk.

How did he get to be this way?

Cholesterol is considered the villain at the heart of heart disease, especially low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol — the “bad” cholesterol. (High-density or HDL cholesterol is considered “healthy”). But this is an incomplete explanation of cholesterol, which functions as a building block of cells, hormones, and enzymes.

LDL particles aren’t inherently worse than HDL particles; they’re made harmful by the Apolipoprotein B (apoB) molecules that wrap around them. These tend to aggregate in the lining of your blood vessels, becoming toxic in the process. This triggers an immune response where your body sends cells to surround them, creating a hardened wall of arterial plaque. The plaque risks rupturing and forming a clot, narrowing your blood vessels, or breaking free and causing a heart attack or stroke.

Plaque in the blood vessels

My takeaway: How should I get rid of the apoB molecules that kickstart this saga? I’m not rushing to get a CT scan to measure my calcium score, but testing my LDL (as a proxy for apoB) is a good start. Attia advises getting them as low as possible — far lower than the 100 mg/dL generally recommended.

As with metabolic resistance, I’ll start with dietary vigilance to curb this if it’s high. Attia (somewhat controversially) recommends using cholesterol-lowering medication like statins for this. Though I understand his logic: no one is low-risk in the long term. It’s still a bridge too far for me right now.

🫀Remind someone to listen to their heart and blood report

III. Cancer

Cancer rates are increasing worldwide, but not because we’re suddenly living sicker lives. It’s because effective treatments for communicable diseases have allowed us — and the cancer cells within us — to live longer lives.

As Siddhartha Mukherjee pointed out in his Pulitzer-winning book, The Emperor of All Maladies:

“Cancer is imprinted in our society: as we extend our life span as a species, we inevitably unleash malignant growth (mutations in cancer genes accumulate with aging; cancer is thus intrinsically related to age). If we seek immortality, then so, too, in a rather perverse sense, does the cancer cell.”

What makes cancer so challenging, though?

Despite making old age (and therefore cancer) more common through improved medicine, our medical arsenal against cancer is relatively limited. Though a few cancers can be treated, our best hope for most is detection when they’re localised and in their early stages.

Once cancer spreads, there’s not much to be done. Chemotherapy can slow it down but not stop it.

Cancer is more challenging to treat than a bacteria or virus because cancer cells are your own cells, just malfunctioning ones. Your body doesn’t perceive them as threats and won’t alert you to their presence early on.

So what can we actually do about it?

According to Attia, early detection through aggressive screening is our best shot, but it’s easier said than done. Conventional medicine avoids this because of the accompanying financial and emotional costs.

Current screening tests aren’t always accurate, so a combination of tests strategically devised for each patient based on their risk profile is our best shot, according to Attia.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one example where aggressive screening can be low-risk and high-reward. You can search for tumours or potentially cancerous polyps through routine colonoscopies and even remove the latter before they become problematic.

Though official US guidelines recommend screening through colonoscopies starting at age 50 and repeating periodically based on your risk, Attia believes age 40 is more appropriate. In 2020, 3640 people under 50 died of CRC; since it’s a slow-moving disease, many who died of it even after 50 likely had it in their systems much earlier.

To understand in depth the potential and pitfalls of current cancer screenings, watch this video by journalist Cleo Abram

My takeaway: Cancer is scary because of the limits to what I can do as an individual to curb it. The inherent randomness in how it emerges and spreads makes it a tricky foe.

I’m starting by exercising and avoiding obesity: it’s linked to 12% to 13% of all cancers, with extreme obesity increasing risks significantly. A fasting-like diet, incidentally, can also benefit treatment. These diets help normal cells resist chemotherapy while rendering cancer cells more vulnerable.

Staying away from cigarettes, vapes, and other sources of smoke is also crucial (which is why I moved out of Delhi two years ago).

Finally, I’ve gifted myself a colonoscopy for my 40th birthday and will keep my eyes peeled and consult a trusted physician for other appropriate screenings.

Cancer is scary. Share this with your loved ones🫂

IV. Alzheimer’s

Neurodegenerative diseases are perhaps the most feared of these all. Though all lead to the same destination, how Alzheimer’s and dementia can destroy your mind along the way feels particularly devastating.

What do we (not) know about it?

Unfortunately, Alzheimer’s isn’t well-understood, which makes it really difficult to treat.

Unlike with heart disease, prevention isn’t easy. Whereas type 2 diabetes can be reversed, this can’t. And unlike with cancer, where some treatments are available, there’s little to be done here.

Alzheimer’s was commonly linked to the accumulation of plaque called Amyloid-beta in the brain, which impaired cognition. This also triggered the production of another protein, Tau, that’s linked to brain shrinkage.

Brain shrinkage due to alzheimers

Recent research challenges this causation, highlighting cases of plaque build-up that didn’t result in Alzheimer’s. Other hypotheses have blamed poor blood flow to the brain due to calcification of blood vessels. Type 2 diabetes can increase your risk significantly because insulin plays a key role in memory function. Certain genetic mutations may render people particularly vulnerable to Alzheimer’s.

Is early intervention possible?

Unfortunately, neurodegenerative diseases can be missed early on. The first visible symptoms — occasional forgetfulness in case of Alzheimer’s or subtle changes in your gait for Parkinson’s — don’t cause alarm. By the time even these show up, though, the underlying scaffolding for the disease has already been laid.

Early diagnoses are also difficult because your brain can initially compensate for certain parts that lose functionality, concealing the disease.

But this highlights possible preventative measures as well, according to Attia.

The more networks you develop in your brain by performing complex tasks, the more fail-safes your brain has. Learning new languages and musical instruments can guard against mental decline, and dancing or boxing workouts can similarly slow Parkinson’s.

Interestingly, hearing loss causes the opposite effect on your brain as learning a language; those who suffer it tend to withdraw from society and, in the absence of stimuli, their brain tends to wither.

My takeaway: I’m not rushing to get tested for the APOE genetic mutations that increase risk (partly because it can cost between 20,000 – 40,000 rupees), but I’m putting habits that would be beneficial either way.

I’m trying to learn more languages (by returning to Hindi books for the first time since 2011) and considering taking dance classes.

Strength training now features regularly in my workouts because Attia’s highlighted an inverse relationship between grip strength and the incidence of dementia.

I treat my sleep as sacred (RIP coffee post-2 PM), because it’s crucial in cleaning waste that accumulates between neurons, and I try my best to control stress levels.

It’s intimidating trying to confront these diseases at the age of 27. Amid the everyday uncertainty of my 20s, I’m trying to avoid a fate that’s decades away. But I recognise this needs to be done. The results of my efforts (or lack thereof) will take decades to show, but I trust that they will.

I started this piece by talking about the sights that scared me into action, so let me end it with ones that have inspired me to keep going: I’ve seen my parents start an ambitious new business in their 60s after technically retiring, and my grandmother travelling the world in her 80s.

So I’m taking my exercise, nutrition, sleep, and mental health more seriously than ever. I’m by no means perfect about it, but there’s more green veggies and protein in my diet, more steps in my day, less screen time before bed, and regular therapy sessions in my schedule.

There’s a lot of life to live, and I want to give myself the best chance of doing that well. To paraphrase Attia, there’s no way to stop growing old, but with the right efforts, I can stay young while doing it.

Want your fam to age like fine wine? Share now