My experiments with sleep

How I used data & science to improve my sleep

The most trustworthy source of food and

fitness journalism in the country.

I struggled to sleep well for around six months in 2019-20. I would go to bed on time but took too long to fall asleep. The quality wasn’t good either: I’d toss, turn, and wake up multiple times during the night.

That was when my workouts were regular, and food was mostly nutritious. Yet, my sleep — the third pillar in this trinity of good health — was suboptimal.

Now my dad and granddad are light sleepers. So I assumed the sleep problem was hardcoded in my genes. (80 per cent of our sleep needs are genetic.)

But was that the full explanation? I felt I was giving myself excuses to do nothing. I wondered if behavioural changes could improve my sleep.

What exactly was wrong? What can I do to improve my sleeping patterns?

I started thinking about these questions because sleep matters—a lot. We spend a third of our lives sleeping. While we don’t exactly know who needs to sleep how much — seven to nine hours is the general recommendation, but it varies — the downsides of less and low-quality sleep are clear: it affects how we think and feel, and it impacts our physical and mental health.

The lockdown was the turning point. It gave me the time to inspect my habits. I went down the internet rabbit hole, read the science and noted the tips for good sleep hygiene. I am a data nerd and wanted to run experiments to see the impact of any changes. So I bought an Oura ring, a smart wearable ring tracking sleeping patterns.

The result of my learning and experimentation?

My sleep has significantly improved: on most days, I get restful and undisturbed sleep, the time to fall asleep has reduced, and I wake up refreshed.

I made a series of changes: I stopped having coffee in the evening, shifted workouts to the morning, started wearing blue light blockers, and fixed my nose breathing habits. I also became more conscious of the relationship between food and sleep.

In today’s article, I will explain why I made these changes and what you can learn from my experience to improve your sleep.

Related on Truth Be Told:

You can’t be ‘healthy’, if you don’t know what it means

Basics first.

There are two key concepts everyone should know about sleep.

First, ‘circadian rhythm’: this is our body’s internal clock set at 24-hour cycles. It governs essential functions — the sleep-wake cycle is one of them.

This internal clock is influenced by external signals, especially environmental light, which is why the sleep cycle is so closely related to the day and night cycle.

Here is how it works: Our optic nerves sense light and dark in the environment. They pass this information from the eyes to a nerve cell group in the brain (called the suprachiasmatic nucleus, or SCN). And this group controls our sleeping patterns.

SCN tells our brain to send alertness signals when we see the morning light. It stops the production of melatonin, the hormone that makes us sleepy. So you feel awake. The opposite happens when it’s dark: melatonin levels spike.

That’s why jet lags are painful. The internal clock is out of sync with the new location’s day-night cycle — the body is confused. So it takes days to bring that in order.

Second, the four sleep stages: While our body is at rest when we sleep, the brain works hard. A lot of activity is happening in the background.

That activity is predictable. Scientists classify it into four stages. These four stages form one cycle, and each cycle lasts around 90 to 110 minutes.

The first three stages are part of NREM sleep, and the fourth stage is REM sleep. (REM stands for ‘rapid eye movement’)

NREM sleep happens first: it is a period of light sleep (stage one) before you enter deep sleep (stages two and three, when it’s so hard to wake up.)

REM sleep happens next, after around 90 minutes of NREM sleep. Your eyes rush from side to side behind closed eyelids. (Really.) The brain activity is so high that you are no more in a deep sleep zone. REM is the stage when you get those intense dreams.

This four-stage cycle keeps repeating as we sleep.

The sleep stages matter to understanding sleep quality: it is not just the number of hours in bed that matters. We want our sleep to be restorative, which requires smooth progression through different sleep stages.

Clear? For a visual explanation, watch this short video from The Economist (it’s terrific!)

Now let me walk you through four specific changes I made to improve the quality and quantity of my sleep.

1. No caffeine after 3 pm

I love coffee — so much love that you could find me drinking black coffee at any point in the day. And I needed a caffeine hit before my evening workout, so my last coffee would generally be around 6 PM.

But then I learned something discomforting: our body’s caffeine sensitivity.

Caffeine isn’t inherently bad. It occurs naturally in plants. But it does alter brain signals post-consumption. Basic chemistry. One specific neurotransmitter, adenosine, matters in the sleep context. It is the chemical that promotes our need to sleep.

Adenosine builds up when we are awake. It keeps accumulating as time passes. It peaks closer to the night and induces sleep pressure after a certain threshold. This is why the longer you are awake, the more you want to sleep. That’s adenosine working behind the scenes.

What does caffeine do? It blocks the adenosine pathway. It prevents sleep pressure creation. That’s why a strong cuppa keeps you awake in a dead boring meeting. That’s also why it can disrupt a good night’s sleep.

Don’t get me wrong: you don’t need to eliminate caffeine from life. You just need to be mindful of its consumption. And it’s timing — which is what I altered in my routine.

The science is straightforward: caffeine has a “quarter-life” of twelve hours, meaning a fourth of the caffeine you consume, say at noon, continues to circulate in your brain at midnight. It doesn’t just flush out instantly. You don’t want heavy doses of caffeine inside your body close to sleep time. So the earlier you stop, the lesser impact it will have on your sleep.

That’s the theory. I wanted to test this out and determine the optimal time for my last cup.

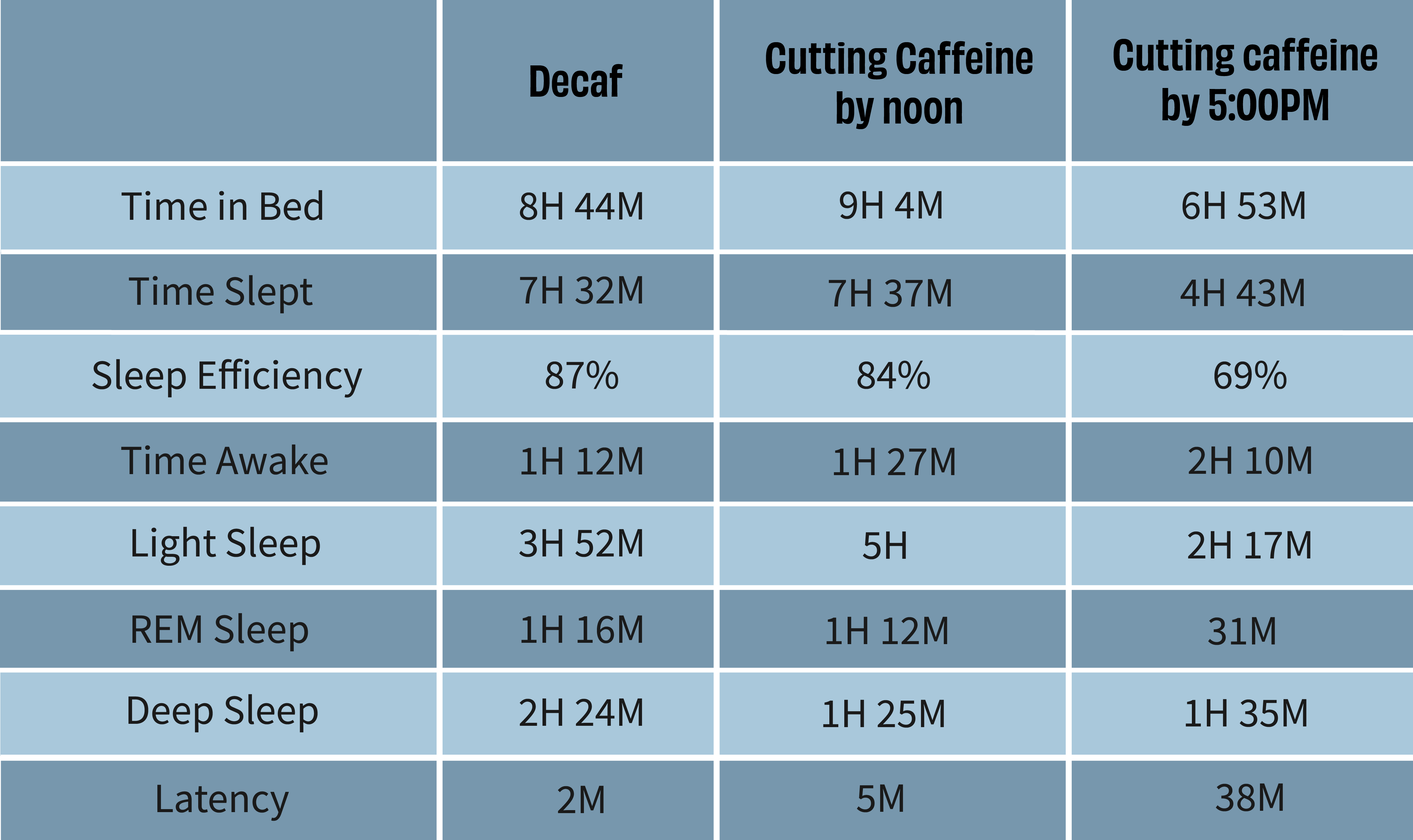

So I ran an experiment for six weeks to improve my sleep. I tried three things for two weeks: going decaf the whole day (so no caffeine), cutting off caffeine at noon, and cutting it off at 5 pm.

To isolate its impact, I kept other variables — nutrition and exercise — constant and observed their sleep implications using data from Oura ring. (Obviously, this is a small-scale personal experiment and not a scientifically rigorous study, so this works for me!)

The table has summary results:

Look at the data. See a row called ‘sleep efficiency’? That’s a good marker of quality and essential to understand my results. It’s a simple concept. Say you sleep at midnight and wake up at 6 am. Is your sleep time six hours? Nope. That’s the number of hours spent in bed — not hours spent sleeping.

Our body can’t achieve 100% sleep efficiency, which is the ratio of total sleep time to the total amount of time you spend in bed. Something in the 80-90% range is good, and between 70-80% is average. Anything below 70% is poor.

What did my experiment find?

Sleep efficiency was at its best in the decaf phase (because there was no caffeine.) It touched 87%, close to the best. But I also saw that cutting caffeine by noon was great for me (though my deep sleep did reduce a bit).

These two strategies had another advantage: data showed I had better quality REM sleep. And it matters because it is that part of sleep where memories are sorted and retained or pruned, and emotions are processed.

The 5 pm coffee phase produced dreadful data. My sleep latency shot up: it took me around 40 minutes to be asleep. And this naturally affected my sleep stages. Both REM and non-REM sleep were affected. Such a bad idea. Some lucky folks can sip their caffeine late in the night and still get a good night’s sleep due to the presence of specific genes. I don’t have them.

What I do now: I aim to complete my caffeine intake by noon. It often stretches to 2 pm or even 3 pm, but I consciously avoid pushing it further.

Insight #1

Avoid caffeine post 3 pm. Try going decaf (so that you get the taste of coffee, at least) if you can’t stick to this time.

2. Workout in the morning

I used to exercise in the evenings —the perfect stress buster after a long work day.

But they were not optimal: I often got a call from work or a friend, or a meeting would come up. My routine would break. So I decided to shift to the morning (around 6:30-7:30 am) to start the day on a high.

This change took effort. The excuses to skip a workout after a tiring day at work were gone. It also made improved my sleep.

I am a morning person, so a morning workout primed my circadian rhythm and optimised my sleep-wake cycle.

Andrew Huberman explained the logic in his podcast: working out early in the morning stimulates the earlier release of melatonin (the sleep hormone) and helps move forward the circadian rhythm. Of course, this would require one to be consistent for a few weeks for our brain to adapt to the circadian rhythm.

Should everyone work out in the morning? Most agree that working out very close to bedtime is not a good idea — it hinders sleep. But the latest research does not prescribe the “best time” to make everyone sleep better.

According to the Sleep Foundation:

Current science suggests there is no one universal time of day that is best to exercise for sleep. Rather, the optimal exercise time likely depends on individual factors such as your chronotype, your age, and any underlying health conditions.

Insight #2

Shifting to morning workouts did have tangible benefits for me and helped improve my sleep. You should try to figure out what works best for you. But avoid exercise three hours before bedtime. And in any case, some workout at any time is much better than no workout. Sweat it out — whatever works.

3. Using blue light blockers

My work involves sitting in front of a screen for a few hours at a stretch. It can stretch to late evenings.

My eyes were often strained and irritated. Rubbing them was my solution but to no avail.

What was happening?

My research led me to the cause: our screens.

Our digital devices — laptops and phones — emit blue light, which passes straight from our retina into the brain. Our eyes can’t block it. That led to the strain.

And then, it also brought me back to the connection between light and sleep. Blue light affects melatonin (the sleep hormone) secretion. It drops, meaning it hinders sleep.

For context: melatonin does not put us to sleep. It just alters the timing of sleep. If sleep were a 100-metre Olympic race, then melatonin would be the official at the start of the race blowing his whistle to commence the race.

So long exposure to blue light leads to more time to fall asleep. This is why it’s always recommended not to use devices closer to bedtime. I keep away all devices from my room around half an hour before sleep. I read myself to sleep.

So I bought a pair of blue light-blocking glasses. The impact was immediate. I can sit for long hours before a screen without feeling strained.

Insight #3

Try blue-light-blocking glasses if your work involves long hours of screen time. It is not necessary to have the glasses on throughout the day; one can start wearing them towards the second half of the day.

4. Breathing

Do you ever wake up feeling tired, with a parched mouth, feeling dehydrated? Or want to visit the bathroom at night while sleeping?

I was this person. I thought this was normal: I didn’t drink water all night, so the body felt the need to wake up and get one glass.

It’s only when I heard an interview of James Nestor on Joe Rogan’s podcast, which led me to his book Breath that I understood this was not expected. It doesn’t have to be this way.

There was a problem: I was breathing through my mouth most of the time. (Healthy people breathe both through their nose and mouth — these two have the air passageways to our lungs.)

Nose breathing has more benefits than mouth breathing, especially concerning sleep. The nose is the preferred breathing route during sleep as it decreases airway resistance. According to one study, nose breathing is an efficient tool to produce vasopressin, the hormone that tells your body to store water overnight and allows the body’s natural circadian rhythm to flow. Mouth breathing does not allow the efficient secretion of this hormone and may cause you to run to the bathroom in the middle of the night. This helps explain why we wake up less when we switch to nose breathing at night.

Mouth breathing can also translate to snoring and lead to heart disease.

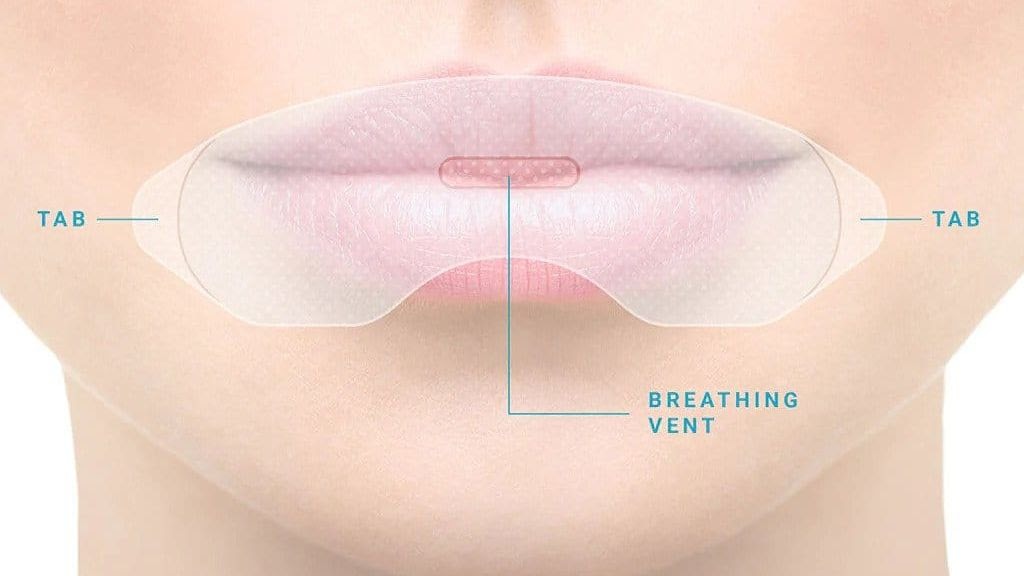

The solution? Mouth taping. It sounds obscure, but that helped keep my mouth shut while sleeping.

It’s not just your ordinary cello tape. It looks like this:

I got one from Somnifix.

There are also cheaper alternatives now on the market.

Here is a video of James explaining the benefits of mouth taping.

Insight #4

If you have signs of mouth breathing, tape your mouth.

Conclusion

These were the hacks that worked for me — that improved my sleep. And it has many other benefits than just waking up refreshed: an improved immune system, better mood regulation, increased productivity and enhanced workouts. And, by extension, it made me healthier.

I will end with a few general guidelines (crowdsourced from various credible resources) that can help everyone:

1. Have a consistent sleep schedule. Wake up at the same time every day, sleep at the same time, including on weekends and vacations. (Hard, I know, but try. It keeps our internal clock happy.)

2. Don’t go to bed unless you feel sleepy. Do something else if you don’t fall asleep within 20 minutes of lying down. Read or listen to music — anything relaxing, and get back when you feel tired enough to fall asleep.

3. Use light to your advantage. I have explained how natural light keeps the internal clock in check. It leads to great sleep. So try letting in some sunlight early in the morning (artificial lights can’t match up). But limit exposure to bright light in the evenings.

4. Stay away from electronic devices at least 30 minutes before bedtime.

5. If you exercise in the evening, don’t do it too close to bedtime. Maintaining at least a three-hour gap can help most people.

6. Avoid eating a large meal just before bedtime.

7. Watch out for caffeine (explained above, avoid after 2-3 pm) and alcohol consumption.

About the author:

Ankush Datar is the author of today’s issue. Outside his full-time job as an investment management professional, Ankush runs marathons and lifts weights, loves reading and biohacking his way to health. He writes a blog on health, investing, and psychology. “I started writing on health and nutrition out of pure passion with the hope that my experiences can help others,” he says.

His experiments to improve his sleep — the focus of his piece — show how learning from science can make tangible changes to everyday life.

Do read and tell us what you think. We will publish a select few responses in a special edition — next week, finally! — where readers get the platform to voice thoughts, feedback and criticism. Ask any questions. Happy reading!

– Samarth (samarth@thewholetruthfoods.com)

More from Truth Be Told

The Definitive Guide to Smart Food Shopping

I solved the mystery of the afternoon slump with CGM

Eight swaps to eat better everyday

Diwali indulgence won’t make you fat

What spikes your blood glucose?

Is your body ageing gracefully?

Should you count calories?

Letters to Editor: Reader Response 01

8 tips to choose the right cooking oil

Why weight loss is a rigged game

You can’t be ‘healthy’, if you don’t know what it means

Food and fitness journalism is broken. We are fixing it.