The Definitive Guide to Smart Food Shopping

Ignore photos. Decode claims. Read ingredients. Call BS.

The most trustworthy source of food and

fitness journalism in the country.

You’re smart. You’re a shopper. And you shop at a friendly, local supermarket that offers a range of ‘healthy’ packaged food options. All’s well.

Food marketers are smart too. And many spend day and night finding (and pressing) buttons that nudge you to buy their product — buttons like “low carb”, “no sugar”, “high protein”, “fortified with iron”, “filled with nuts”, “loaded with antioxidants” and so on.

I used to be one of them. I sold face washes that ‘help’ reduce pimples in just four washes and skin creams that make your skin ‘fairer’ in two weeks. The proverbial penny dropped when I realised my counterparts on the food side were doing the same. So I started The Whole Truth and made it my mission to be the insider who tells you the tricks of the trade.

Today’s article is my attempt at summarising all I’ve learnt about smart food shopping. It’s not that difficult. The marketeer might be clever. But so is the regulator. All the information you need to know lies in plain sight on the back of the pack. All you need is some help to uncover the truth. Allow me to help.

1. Ignore the Photo.

At the supermarket, we all start with the Front of the Pack (FOP). Mistake. That FOP is like a matrimonial ad: it only tells you what they want you to know — not what you really need to know. And the most significant part of most FOPs is the photograph.

That beautiful bowl of muesli with milk splashing all over. That decadent bar of chocolate with almonds flying all around. That irresistible stack of pancakes with a glossy dollop of honey. Mmmmh.

All that beauty — ignore it. Why?

Think of the food photo as a Tinder profile pic. Every guy has a guitar, a dog, an unruly mop of hair, and a picture that magically cuts off right where his pot belly begins.

So please don’t become a victim of food photo catfishing: they are massively done up and borderline fake. Engine oil replaces honey on pancakes (because it doesn’t absorb and remains glossy). Glue replaces milk in a bowl of cornflakes (cornflakes would go soggy in real milk). The number of almonds flying out of a muesli photo is 10x of what you’ll find inside the packet. And all the garnishing around that noodle bowl isn’t inside the pack.

That’s why you’ll always find a small * mark that says ‘creative visualisation’ or ‘contents in the pack might not resemble this picture’ — because it’s not real.

So train yourself to ignore the photo. Because next, you have a larger demon to deal with . Claims.

Like what you see so far?

Get TBT articles in your inbox every Saturday

2. Decode the Claims.

Claims are features the food manufacturer ‘claims’ a food has: high protein, low-sugar, no-preservatives, diabetic friendly, keto-friendly, packed with antioxidants, rich in iron — all these are claims.

There are three broad categories I repeatedly find. Let’s decode each.

One: “High-Low”

High protein. Low-carb. Low-fat. These are the most common claims you’ll find on food packets. They are the easiest to make.

Think about it: If a cookie has three grams of protein, is that high or low or medium? Who is to say?

Same with low-fat. Lower than what? And then you’ll find a * mark that says: ‘as compared to our previous recipe’. So lower compared to your own high standards. Amazing.

My general rule: ignore all the High-Low claims. Instead, turn to the nutritional table at the back.

India’s food regulator, the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India, or FSSAI, has one great rule: it mandates that all macronutrients (proteins, carbs, fats) and micronutrients (vitamins and minerals) and anything else about which a claim has been made on the front of the pack, must be declared, with exact quantities, on the nutrition table.

So let’s say your cookie pack screams “protein-packed”. You turn the pack and find each cookie has 2gm of protein. Compare that with your daily protein goal, say it is 60-70 gm — now you decide whether it’s high or abysmally low.

A word about Serving Size

Unfortunately, calculating protein in one cookie is not that simple.

FSSAI mandates that manufacturers declare nutritional values ‘per 100gm’ or ‘per serve’. But the definition of what constitutes a ‘serve’ is left to the manufacturer.

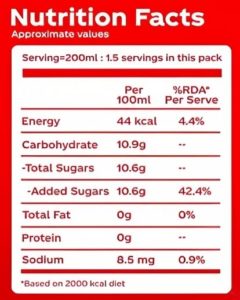

And that leads to bizarreness. Example: you pick up a 330ml can of cola that declares values ‘per 100gm’ and says one serve is 200gm.

What does that mean? This one can has 1.5 serves (one gm is one ml) — so you’re supposed to consume 65% of the can and keep the rest. And the next time you want another ‘serve’, drink the 35% from last time and another 30% from a new can and keep the rest. Huh?

Nutrition facts of a 330ml can of cola

So yeah, the manufacturer decided serving sizes don’t help. The best way is to derive values as per your actual serving size.

Here is how: If your 100 gm packet has 8 cookies, and in one go, you eat two, then your serving size is 25gm. So if a 100gm packet has 16gm protein, your serving size has 4gm. Do the same math for calories, fat, or any other macro you watch. That’s it.

Two: “No Nasties”

The next most prevalent type of claim starts with “no”: no added sugar, no artificial flavour, no added colour, no preservatives. The list goes on. The most harmful one, though, is no added sugar. Let’s dive deep into that.

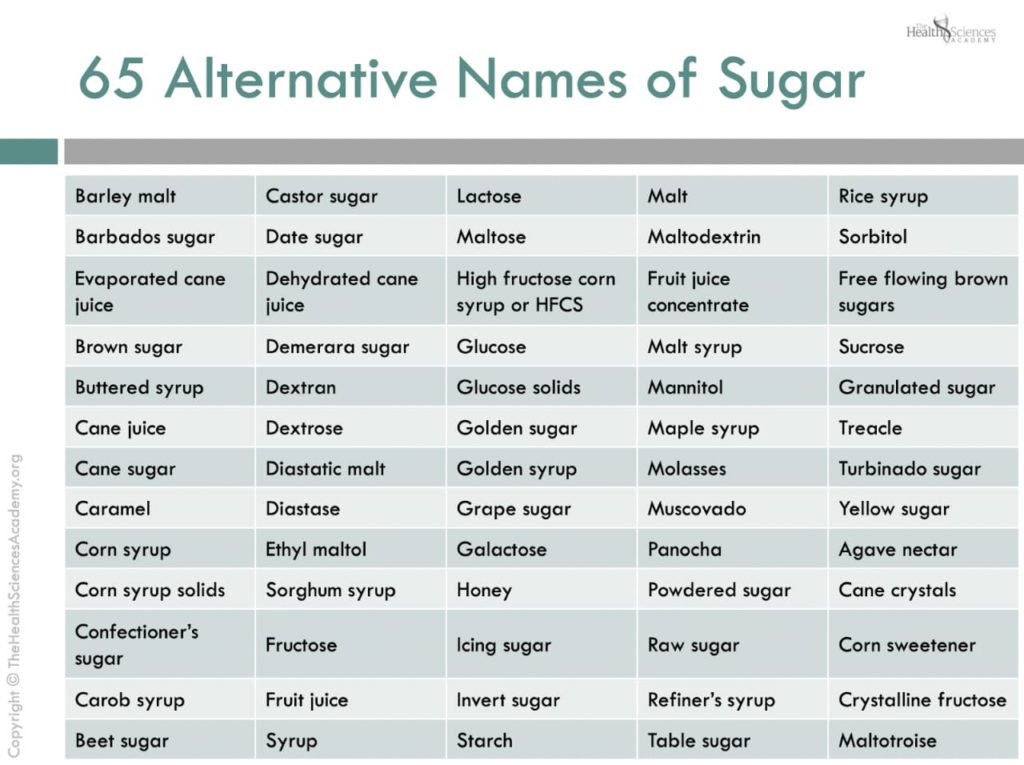

These are the biggest bane of modern-day food. Manufacturers know all of us love sweet stuff. They also know we’re all trying to reduce sugar intake. The result: you have over 60 different forms of sugar that don’t need to be classified as sugar. So manufacturers add them and still claim ‘no added sugar’. Nuts.

That’s the list. You can’t — shouldn’t — memorise it. But I’ll teach you the top four types, and you’ll be a pro at spotting them.

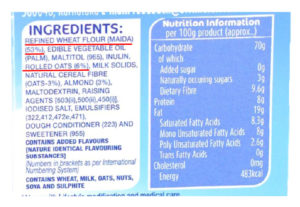

B) Sugar Alcohols

If you find any word in the ingredient list that ends in “OL”, it’s a sugar alcohol: maltitol, sorbitol, xylitol, mannitol — these are the most common examples.

Sugar alcohols are sweeteners that usually have half the calories of sugar. Because, unlike regular sugar, your small intestine doesn’t absorb sugar alcohols well, so fewer calories get into your bloodstream. The remaining get excreted.

But because sugar alcohols aren’t completely absorbed, you might get gas, bloating, and diarrhoea if you eat too many. That’s why you’ll find the disclaimer ‘acts as laxative’ on some food packets containing sugar alcohols.

Sugar alcohols in a biscuit can cause laxative effect

Sugar alcohols aren’t sugar. But they still have half the calories and insulin impact. So spot them, and account for them.

C) Glucose and High Fructose Corn Syrup

Any ingredient ending in “OSE” is a sugar, too: glucose, dextrose, fructose — these are all sugars. And High Fructose Corn Syrup (HFCS) is the most prevalent and problematic.

Regular sugar is a disaccharide. Where “di” means two and “saccharide” means sugar. So regular table sugar is a combination of two sugars — glucose and fructose. Half each.

HFCS, as the name suggests, is sugar with higher fructose. 55% fructose and 45% glucose. Hence, it has a 40% higher Glycemic Index (GI) than regular sugar.

(Reminder : GI measures how quickly food causes our blood sugar levels to rise. Foods with lower GI are digested and absorbed slowly, and gently release glucose, which is good. Higher GI foods are not.)

Also, it’s made from corn which is far cheaper than sugarcane, which led to a massive proliferation of HFCS in all sorts of foods. From pasta to salad sauce to your favourite cola, it’s everywhere.

D) Maltodextrin

It acts the same as sugar, has a GI worse than sugar, and is not declared sugar. So no wonder manufacturers who want to claim ‘sugar-free’ on their packets are going to town with this ingredient. Chances are it’s in your soup, your pizza base, the seasoning of your chips, and the base of your dips.

E) Artificial sweeteners

These are zero-calorie sweeteners: aspartame, saccharin, and sucralose are famous. Yes, they have zero calories, but they aren’t as innocent as they seem. They were discovered over 100 years ago, they were supposed to curb the rise in global obesity, but they didn’t. Why?

Research suggests many reasons.

First: We overcompensate. So we have that diet coke, feel good about our discipline, and celebrate with a piece of cake at night.

Second: Artificial sweeteners don’t release any calories because our bodies can’t digest them. They pass right through our gut. But the body doesn’t know that this sweet thing you ate has sugar or sucralose. So it still secretes insulin, expecting a glucose spike that never comes.

Third: Artificial sweeteners allow us to fool ourselves. They give us an easy way out. We feel we can have all the cake and cola without any repercussions. That means we never learn control. Never learn to say no to bad food. Since we never develop that muscle, we invariably falter.

Basically, with food, as with life, if it’s too good to be true, it probably is. So if your packet says ‘no added sugar’, don’t trust it. Instead, turn the pack, read the ingredient list, and if you spot any of the above, know better.

3. Helps with. Known to. Goodness of. Friendly. Packed. Rich.

The next category of claims are the ones written by masters of the English language. And of law.

This green tea “helps with weight loss”. This bar contains turmeric which is “known for its anti-inflammatory properties”. This cookie is “diabetic-friendly”. That meal is ‘keto-friendly’. Bullshit.

I’ve listed above the most common ways English phrases that mean nothing but absolve the claim maker from legal action are used.

Because hey, I did pack two grams of protein into this cookie. So it’s packed. And these cornflakes have some iron, so they aren’t iron-poor. Right? And I only claimed that green tea would help with weight loss. And I’m sure it did. Can you prove otherwise?

The one that gets me most riled up though is diabetic-friendly. What does it even mean?

Oh, you say it means low sugar? Sure, let’s see the ingredient list. But, oops, instead of sugar, it has maltitol — sugar alcohol. Which has a lower Glycemic Index than sugar, and people with diabetes must avoid high GI foods as their insulin response is broken.

But here’s the problem. People with diabetes are supposed to manage GI throughout the day. The combined impact of ‘everything’ they eat. But they can’t do that because your cookie says it’s ‘friendly’, which, to laymen, means they can have this without guilt and without adding it to their calculation. Yet, it’s adding to her Glycemic Load

Same with Keto-friendly. To stay in keto, you need to eat less than 25-30 gm of carbs throughout the day. This bar might have 10g carbs, so individually it won’t put me out of keto. But what if I have three of these bars in the day. Will they be ‘unfriendly’ then?

A word about qualifiers. And slyness.

What if I just called it a ‘protein cookie’ or a ‘keto cake’. There’s no claim now. It’s just a qualifier. Yet, it achieves the same effect — without any legal consequence.

Sigh. Beware.

Like what you see so far?

Get TBT articles in your inbox every Saturday

3. Read the Ingredients

Knowing what you know now, you can’t be trapped by the food marketeer. Their playground is the front of the pack, which you’ve successfully navigated. Now play offence. Turn to the back of the pack (BOP).

On the BOP, the biggest treasure trove of information is the ingredient list. Here are my three rules on how to read it.

One: What’s the first ingredient?

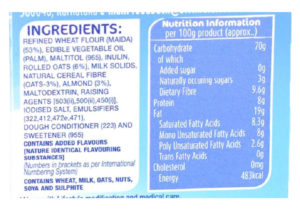

The FSSAI mandates that ingredients need to be listed in decreasing order of constitution. So the first ingredient on that list is the largest component of your food. Then the next. And so on. Take this packet of oat cookies. The first, and hence, the largest ingredient, is Refined Flour (maida). Then there is Vegetable Oil, the second largest. Then there is Maltitol. And something called Inulin. And then, finally, there are Oats. Which is just 6%.

The back of pack of an oat cookie

Similarly, don’t be surprised if the first ingredient in your chocolate is sugar, and in your atta noodles is maida. Read the list.

Two: What’s the percentage of each ingredient?

Unfortunately, FSSAI doesn’t mandate that the portion of each ingredient be declared. Interestingly, you’ll find the manufacturers self-declaring the percentage of a select few ingredients. In our example, for instance, the % of flour and oats is selectively displayed. The rest isn’t.

Why is that? Regulation.

The FSSAI mandates ingredient portions for stuff emphasised on the front of the pack (through labels or pictures, like oats) or those essential to that food (like flour is to biscuit). The rest get a freeway.

That is how the regulator ensures you know there’s just six per cent oat in the cookie before you buy it as an ‘oat cookie’. But that does not ensure you know the percentage contribution of the rest.

But you can know. You can at least estimate.

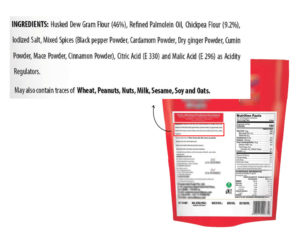

For example, take this aloo bhujia.

The back of pack of a aloo bhujia

They declare that 46.2% is husked dew gram flour (besan), and 9.2% is chickpea flour. They had to display these two because they are essential to what we expect from bhujia. But the ingredient between the two is oil, and they haven’t mentioned how much oil.

Let’s find out.

Since ingredients are ordered by weight, you know that oil has to be less than 46% and more than 9% — 46+9 = 55%. Meaning 55% of this packet is these two flours.

They haven’t mentioned the % of any other ingredients, but they are salt and spices: how much can they be? Maybe 3%? 5%? Not more than that. Add that. So 60% is gone. What’s left? Only oil. That makes the rest. 40%.

So yes, 40% of this bhujia might be oil alone. Voila.

Learn this basic math.

Three: What’s the number of ingredients?

If the ingredient list has 25 ingredients, that’s a red flag. Because usually, good food is simple. It only needs six to eight ingredients or four to five/ food groups.

So your grandma’s ‘kadai paneer’ recipe might have 20 ingredients, but it’s actually five veggies, ten spices, salt, oil, water and paneer. Just five to six food groups.

So whenever you see a very long list, beware. Especially if half the names are stuff you can’t pronounce. This brings me to the last set of nasties.

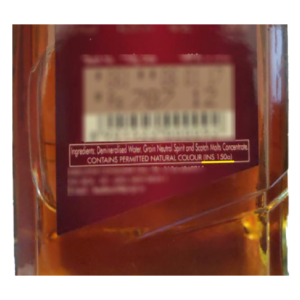

Four: Food with numbers

All the INS or E numbers you see behind the food pack are either synthetic colours, flavours, preservatives, or thickening and stabilising agents. INS means International Numbering System for Food Additives, and E numbers are their European Union equivalents.

By definition, E-numbered foods give no nutritional benefit. They are there merely to perform a chemical function. That function might be imparting a specific flavour, binding, anti-caking, or preservation.

If I want to enhance the flavour in my packaged soup, I might add E621, a flavour enhancer. Also known as MSG or monosodium glutamate.

Or If I want a cookie to look dark brown, even though it’s made with maida, which is white, I’ll put in INS 150a. And I’ll have a caramel colour — and the colour will trick your mind into believing this is healthy. Because hey, brown = whole grain = healthy!

Even your whiskey, for God’s sake, has INS 150a. Brown colour. Just so it’s the right brown for you to feel it’s premium.

Food colour in whiskey

Now, not all chemicals are bad. Human beings created chemicals to make life easier, and some do that function. Take baking soda, or sodium bicarbonate. It’s been used for ages in cooking. Not bad. And yes, these additives have been deemed safe for consumption by your local food authorities, meaning you won’t die if you eat them.

But changing food’s colour, taste and texture changes our relationship with it. If something with no blueberries in it starts tasting like blueberries, our mind starts thinking, ‘oh great, fruit’ and starts having more of it. Same with something that isn’t brown but looks brown. Or something that becomes extra tasty with MSG.

So here is my personal rule: avoid numbers in food as far as possible. Keep the food real. Let the body understand what it is having and it’ll do nothing to harm itself.

That’s it. Next time you’re at the supermarket and pick a food packet, you know what to do.

Ignore the photos. They’re not real.

Decode the claims. They hide more than they reveal.

Turn the pack, read the ingredient list, and choose simple food. Made with a few ingredients, most of which you can pronounce.

Do this, and the food marketeer has no power over you. You’re titanium.

Happy shopping!

Click the logo to sign up for the newsletter

More from Truth Be Told

Safest cooking utensils for healthy living

Your brain needs to relax and here’s how you can do it

Here’s how I got my cholesterol levels down

Why you can’t eat just one chip

I solved the mystery of the afternoon slump with CGM

Eight swaps to eat better everyday

Diwali indulgence won’t make you fat

What spikes your blood glucose?

Is your body ageing gracefully?

Should you count calories?

Letters to Editor: Reader Response 01

My experiments with sleep

8 tips to choose the right cooking oil

You can’t be ‘healthy’, if you don’t know what it means

Food and fitness journalism is broken. We are fixing it.