The Palm Oil Problem Isn’t What You Think. (But Why Is It Everywhere?)

The most trustworthy source of food and

fitness journalism in the country.

Editor’s note: Dear readers, sending out a newsletter today feels strange. With the tensions brewing at the border, much of the work feels irrelevant. It’s the first time in my adult life that war feels like a real possibility—and I’m unsure how to act, or what to say. I considered skipping today. But I’ve chosen to publish anyway, trusting that you share this discomfort—and will understand.

Today’s story genuinely surprised me. Like many of you, I’d always heard palm oil was bad. I never really questioned why—I just assumed it must be. I asked Anushka Mukherjee to find out (regular readers should now be familiar with her deep-dives), and when she got back with her research, I realised the narrative around palm oil is… off. The ingredient has been villainised—but the real problem is the system.

So here it is: how palm oil quietly took over our food—and what that says about modern eating. Give it 12 minutes. I promise it’s worth your time.

PS: Here is a short feedback form to help us understand how we’re doing. Would you please share your thoughts? Link here. Thank you!

– Samarth Bansal (samarth@thewholetruthfoods.com)

I. The silent rise of vegetable oil

The biggest change in our diets over the last century hasn’t been about sugar. It hasn’t been carbs.

It’s been oil—specifically, refined vegetable oil.

Today, these oils quietly deliver nearly 300 calories per person, per day—about 10% of all food energy globally, and more than double what it was in 1961.

But the real story isn’t just how much we consume. It’s how invisibly it happened. Vegetable oil has slipped into your bread, your chocolate, your instant noodles—and you probably haven’t noticed.

Don’t get me wrong: humans have cooked with oil for thousands of years. Indian cuisines especially begin with fat—mustard oil, coconut oil, ghee, sesame. That’s not new.

What changed is how oil moved from the frying pan into the factory. From being something you cook with, to something that shows up in food you didn’t cook at all. And that shift—quiet, industrial, and massive—is linked with the longest-running debates in modern nutrition: Is fat good or bad? Saturated? Unsaturated? What about cholesterol? What about heart disease? The answers kept changing.

First, butter was bad and margarine was great. Then, butter became kind of okay, but margarine was worse. Eventually, we just settled for: less oil is probably safer.

And at the center of this confusion sits one ingredient: palm oil. It is in half the packaged food you eat. It’s the most widely consumed edible oil in the world. And yet, it might also be the most misunderstood.

It’s not evil. It’s not miraculous. It’s just… engineered to be everywhere.

But to understand this, we first need to understand fats—and why they make food so irresistible.

II. Why fats make food delicious

Fat is powerful. It gives food richness, aroma, and deep satisfaction. At 9 calories per gram, fat carries more than double the energy of protein or carbohydrates—which the brain rewards with pleasure.

But it also does something they can’t: it carries flavour. Many aromatic compounds are fat-soluble, not water-soluble—they dissolve and release in fat. This is why a dish comes alive with even a small amount of fat; it unlocks flavours that would otherwise remain trapped and undetectable.

If you’ve cooked Indian food, you already know this. Nearly every dish begins with a little fat in a hot pan. In the south, curry leaves and mustard seeds are fried in coconut oil. In Bengal, nigella seeds sizzle in mustard oil before anything else is added. In the north, cumin seeds (jeera) are browned in oil to start the dish.

We’ve always known this instinctively: fat brings flavour to life. A little soft butter on bread is transformative. So is a drizzle of fragrant olive oil on a salad.

As chef and author Samin Nosrat writes in Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat:

“Without the flavours and textures that fat makes possible, food would be immeasurably less pleasurable to eat.”

We don’t just eat fat. We feel it.

But all fats do not behave the same way.

III. Solid fats. Liquid fats.

The most important difference to understand—especially for this story—is between fats that are solid and fats that are liquid at room temperature.

Think of solid fats like butter and ghee as structural elements. When you fold butter into pastry dough, it creates separate layers that puff up in the oven. When you cream butter with sugar, it traps tiny air bubbles that expand during baking, making cakes rise. When solid fat in chocolate hardens, it creates that satisfying snap when you break a piece. All of these effects require fat that can hold its shape.

Liquid fats—like mustard, sunflower, or soybean oil—can’t perform these structural roles. They flow rather than fold, mix rather than layer, and won’t solidify to create firm textures. They’re excellent for frying and sautéing, but they simply can’t build the architecture that makes pastries flaky or ice cream creamy.

But there’s a catch: most solid fats come from animals. And they’re expensive. You have to feed the animal, milk it, or slaughter it.

The food industry went on a hunt to find a replacement for solid animal fat. Something with the structure of butter—but cheaper. A solid fat that didn’t spoil quickly, didn’t require refrigeration, and wasn’t tied to animals.

How to find one?

IV. The hunt for cheap solid fat—and the birth of industrial oils

The answer came from… chemistry.

In 1901, German chemist Wilhelm Normann discovered hydrogenation—a process that transforms liquid oils into solid fats by heating them with hydrogen gas under pressure.

“If you hydrogenate the oil fully, you get fat that’s hard like ice. But if you only partially hydrogenate, you can make any melting profile you like, which makes it possible to produce a fat that’s solid at room temperature but still easy to spread out of the fridge,” author and physician Chris van Tulleken writes in his book Ultra-Processed People.

By 1909, this method was ready for commercial use.

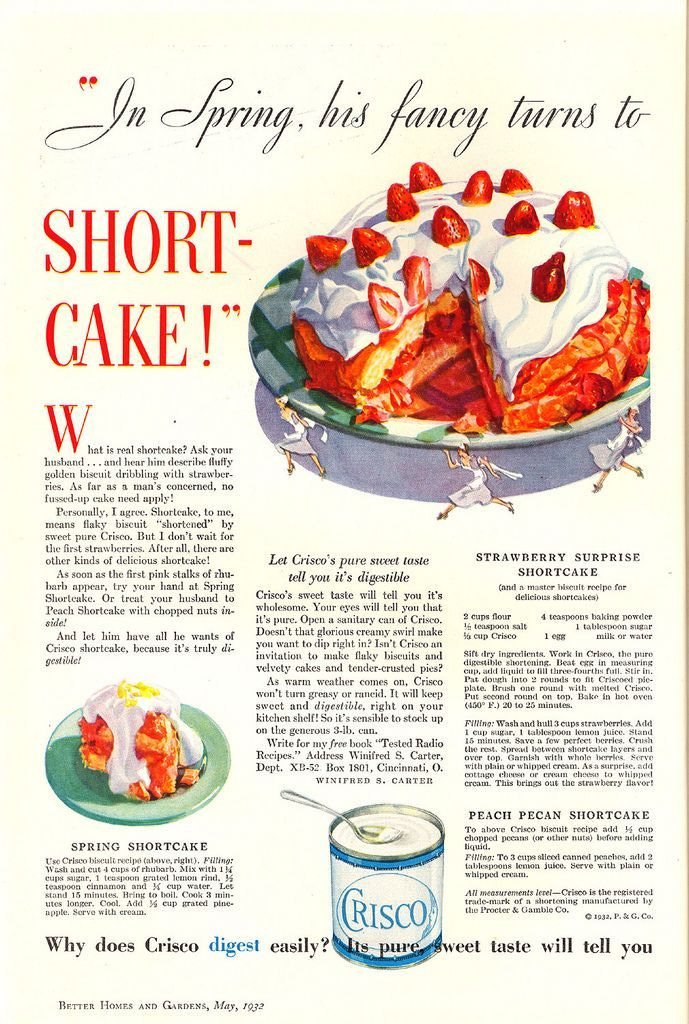

Procter & Gamble, a young soap company, immediately saw potential beyond soap-making. They now just needed the cheapest possible oil source. Their solution? Cottonseed—a worthless byproduct of the cotton industry. When hydrogenated, cottonseed oil became a soft, white substance remarkably similar to butter, but cheaper and with a longer shelf life.

In 1911, P&G launched Crisco—short for “crystallized cottonseed oil”—marketing it as digestible, pure, and convenient. Unlike butter, it didn’t spoil and worked beautifully in baking.

The idea spread quickly. Unilever launched Spry, another vegetable shortening. In India, a similar product appeared as Vanaspati ghee, later rebranded as Dalda in 1937—a cheaper alternative to traditional ghee.

By the 1970s, American families used more margarine than butter, a shift accelerated by health recommendations. In the 1960s, the American Heart Association began advising people to reduce saturated fat intake, based on research linking it to higher cholesterol. By 1980, this became official U.S. government policy.

And then the fat debate took an unexpected turn. In the 1990s, scientists discovered something alarming: the partial hydrogenation process created trans fats, which proved even worse for heart health than the saturated fats they were meant to replace. (The U.S. banned partially-hydrogenated oils in 2015; WHO targets a global phase-out by 2025.)

Step back and see the pattern: the food industry solved one problem (expensive animal fats) only to create another (dangerous trans fats). Now they faced a crisis. They urgently needed another solution: a semi-solid fat that was stable, cheap, and trans fat-free.

That’s when palm oil stepped in. And it was exactly what they needed. Well…they turned it into exactly what they needed.

V. The rise of palm oil

Palm oil didn’t just arrive. It fit in. Perfectly.

It is naturally semi-solid at room temperature, just like butter. It is stable at high temperatures, perfect for frying. It doesn’t require hydrogenation, so no trans fats. It doesn’t go rancid easily, so it has a longer shelf life than almost any other edible oil.

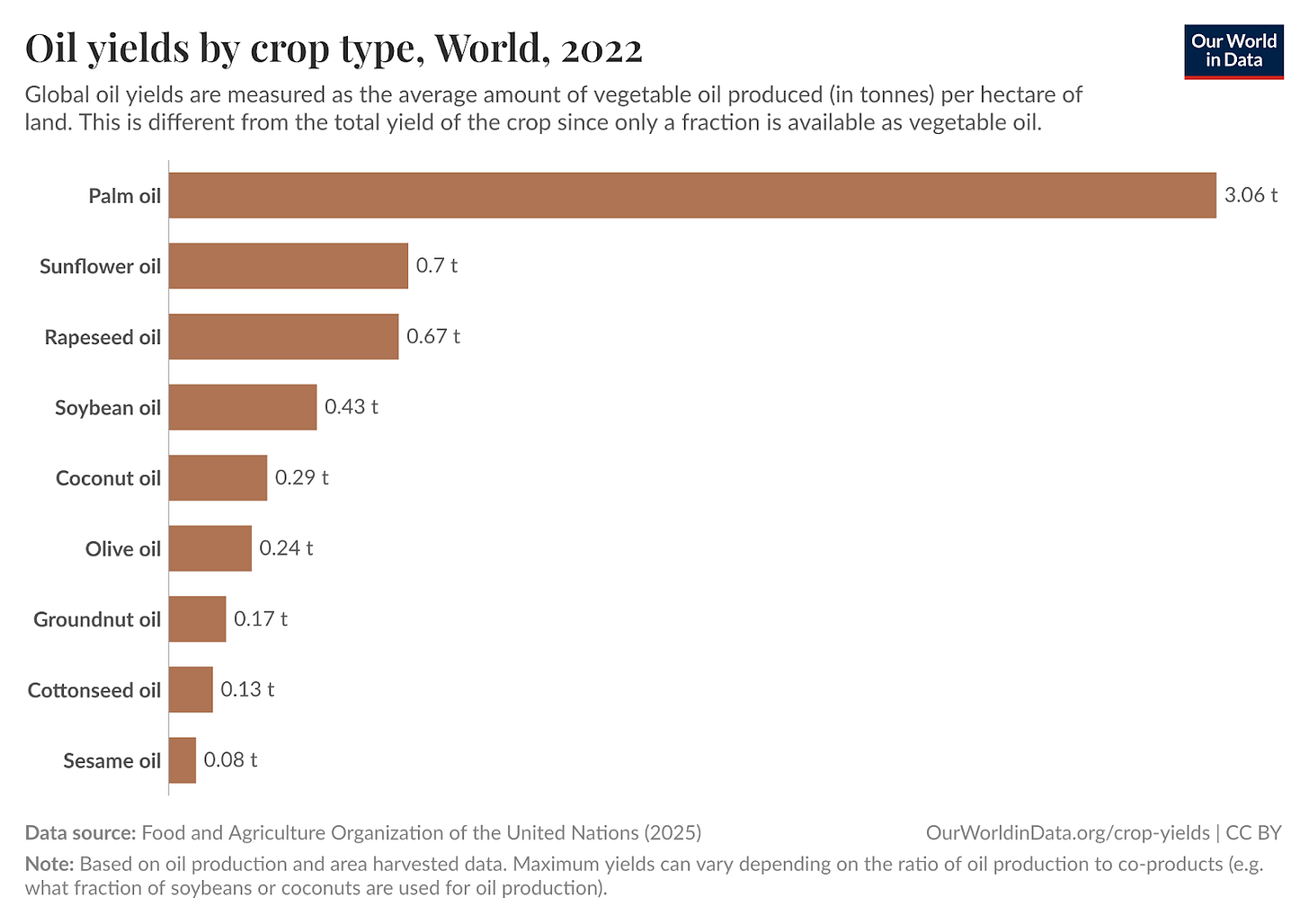

And it is ridiculously productive: oil palm trees yield about 3 tonnes of oil per hectare, which is 4-10 times more than soy, sunflower, coconut and groundnut.

That makes palm oil absurdly cheap to produce. In 2024, palm oil cost around $800 per tonne, while butter cost more than $8,700 per tonne. Eleven times cheaper.

This offered the food industry what no other fat could: functionality, scale and price. That too, as a “healthier” replacement for hydrogenated vegetable oil because “trans-fat free”.

The switch was quick. Almost overnight, in 1994, Unilever had to swap out 600 blends across 15 countries with palm oil. So did other massive companies: both for food and personal care.

Suddenly, palm oil was everywhere. It replaced cocoa butter in chocolate, milk fat in ice cream, and butter in baked foods.

And the consumer? Barely noticed.

Because industrial palm oil doesn’t announce itself. It’s neutral. Odourless. Tasteless. It doesn’t spoil. It works invisibly—which is exactly what the industry wanted.

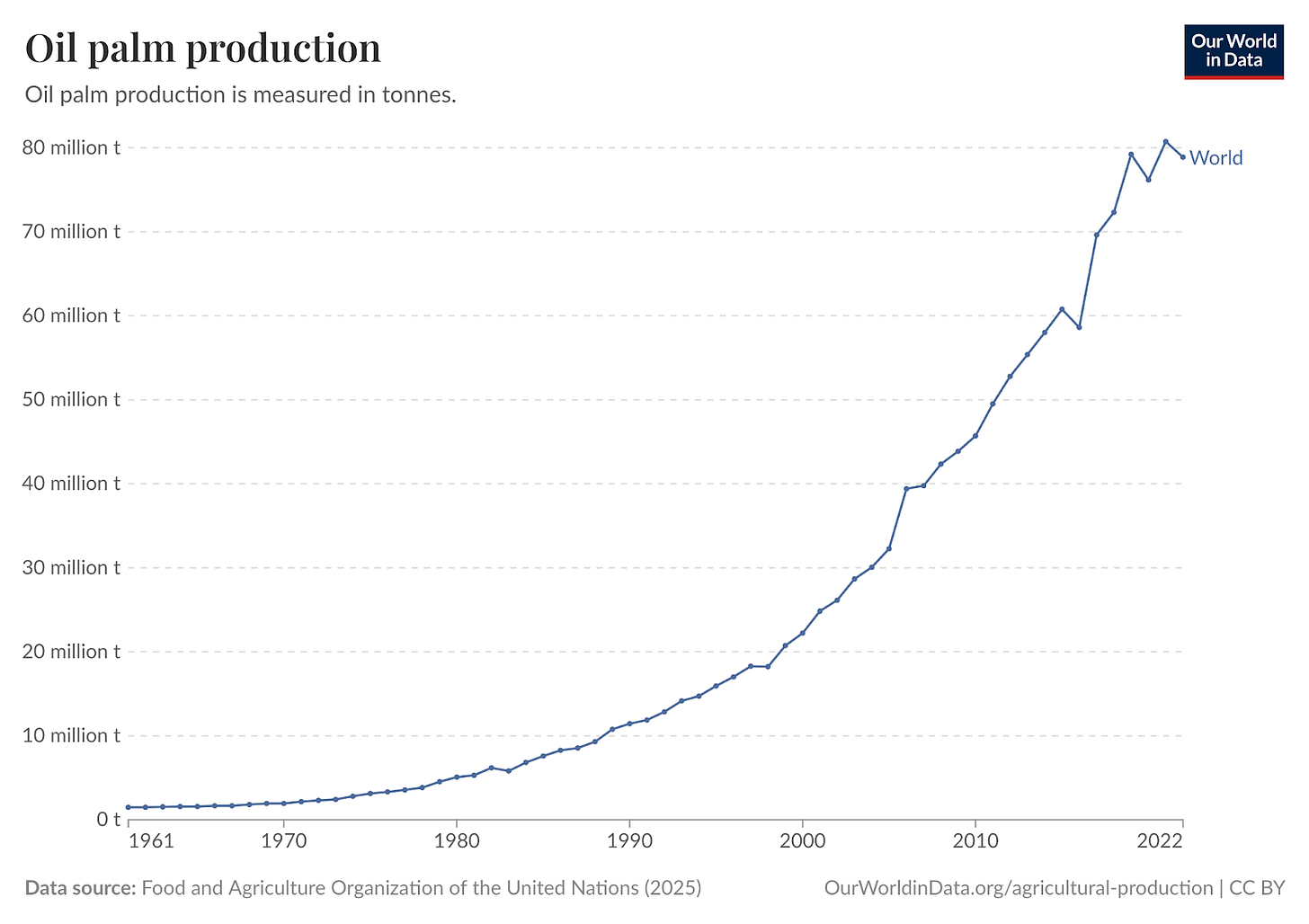

And so, the world’s palm oil production exploded: between 1970 and 2020, it increased by about 40 times.

Palm oil solved a lot of problems, and got rid of all the trans fats from our food. So, why does it get a bad rep?

VI. Is palm oil a problem?

Nutritionally speaking, palm oil is not the villain it’s often portrayed to be. Yes, it contains about 50% saturated fat, and excessive saturated fat consumption has been linked to heart health concerns—that’s been a central debate in nutrition science for decades. Current dietary guidelines recommend limiting saturated fats to less than 10% of daily calories.

But put that in perspective: palm oil (50%) sits in the middle of the spectrum—lower in saturated fat than butter (60%), ghee (65%), and coconut oil (85%), yet considerably higher than olive oil (14%), canola oil (7%), or sunflower oil (12%).

Hero? No. Villain? Umm… no. So what is the problem?

1. Industrial palm oil bears no resemblance to traditional palm oil

Traditional red palm oil has sustained West African communities for over 5,000 years. This bright crimson, aromatic oil is treasured as ‘red gold’—not just for its rich flavour and nutritional value, but for its ceremonial and spiritual significance. It’s a vital ingredient in traditional dishes like Banga soup and served with boiled yam.

What we consume today is fundamentally different. In Ultra-Processed People, Tulleken points out that the palm oil listed on product packages is industrial palm oil, stripped of its original character.

He writes: “When freshly pressed, it’s an almost luminous crimson, highly aromatic, spicy and flavourful, and full of antioxidants like palm tocotrienol. But, for UPF (ultra-processed food) manufacturers, all that flavour and colour is a problem rather than an advantage. You can’t make Nutella with spicy red oil.”

The industrial solution? RBD—Refine, Bleach, Deodorise.

Manufacturers heat the oil, strip it with phosphoric acid, neutralise it with caustic soda, bleach it with bentonite clay, and deodorise it using high-pressure steam. This aggressive processing transforms a vibrant, nutritious oil into a bland, flavourless, shelf-stable fat that’s practically interchangeable with any other industrial fat.

2. Moderation is hard. By design.

Palm oil—like most fats—is fine in moderation. But here’s the problem: how do you moderate something that’s in nearly half of all packaged foods?

The real health risk isn’t from a teaspoon used in home cooking. It’s the cumulative invisible load. Palm oil hides in cookies, spreads, instant noodles, chocolates, ice cream, and countless other products. In India—the world’s largest palm oil importer—it’s even the primary oil used in street food.

When a single ingredient silently accumulates across your diet, moderation becomes meaningless. You’re consuming it constantly, at levels far beyond what you’d consciously choose, without even knowing it’s there. That is the problem.

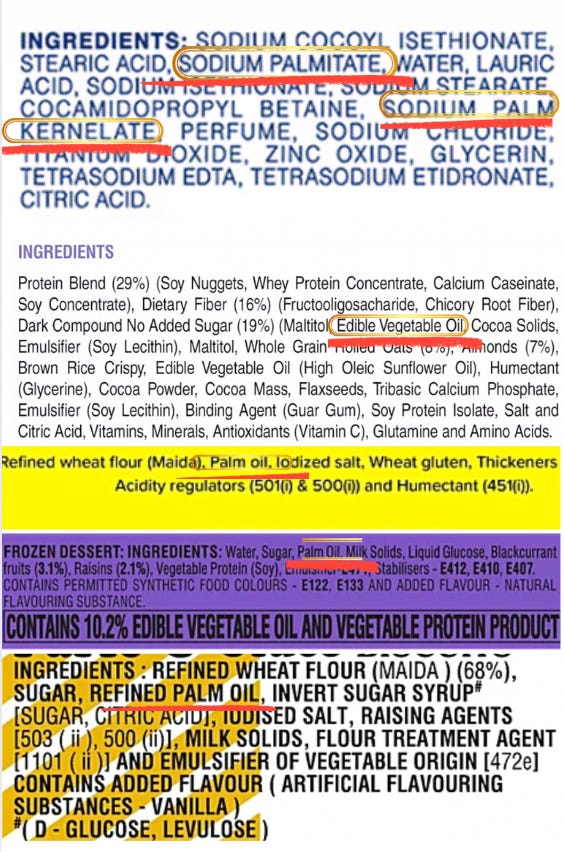

3. The many names of palm oil

Vegetable oil. E471. Glyceryl. Sodium lauryl sulfate. Stearic acid. Cetyl alcohol. Elaeis guineensis.

What are these? All palm oil.

There are more than 200 different names for palm oil derivatives on ingredient labels, and just around 10% contain the word “palm.” This is systematic obfuscation.

When manufacturers hide ingredients behind technical terms and generic labels, they strip away your ability to choose what goes into your body. Even the most vigilant label-readers are left in the dark, unable to track or limit their palm oil consumption.

4. It removed natural friction from our food system

Throughout history, natural constraints shaped our relationship with fats. Butter required dairy animals. Olive oil demanded suitable climates and careful pressing. Cocoa butter meant growing, harvesting, and processing cacao beans.

These limitations created a relationship of respect. When something is scarce or labor-intensive, we use it intentionally. We appreciate its unique properties. We develop traditions around its use. We notice it on our tongues and in our dishes.

But palm oil—industrially refined, impossibly cheap, and functionally versatile—shattered these constraints. At $800 per tonne versus butter’s $8,700, it removed all barriers to unlimited fat in processed foods. When a structural fat is this abundant and this cheap, it gets used not just where needed, but wherever possible.

Without realising it, we’ve moved from savouring fats intentionally to consuming them unconsciously—palm oil appears in everything from cookies to cosmetics, often for reasons more economic than culinary.

This is the hidden power of ultra-processed food: it doesn’t just change ingredients. It changes our relationship with eating. When natural limits disappear, so does our awareness of what we consume.

I can’t imagine having the same reverence for palm oil as its traditional cultivators in West Africa. For me, it’s just another ingredient: and now it’s in so much processed food that all I want to do is avoid a packet with the word palm oil.

5. The true cost behind palm oil’s bad reputation

The biggest reason palm oil gets bad press is its environmental impact. The numbers tell the story.

- Indonesia and Malaysia produce 85% of global palm oil. Between 2001 and 2023, around 10 million hectares of forest were converted to oil-palm plantations—that is a land-grab a little larger than the entire area of West Bengal.

- A third of new plantations are built on peatlands, which store vast amounts of carbon. When drained and burned, these soils release massive carbon emissions and create the toxic haze that chokes cities across Southeast Asia.

- The wildlife cost is equally severe. Habitat loss threatens orangutans, Sumatran tigers, and thousands of plant species found nowhere else on Earth.

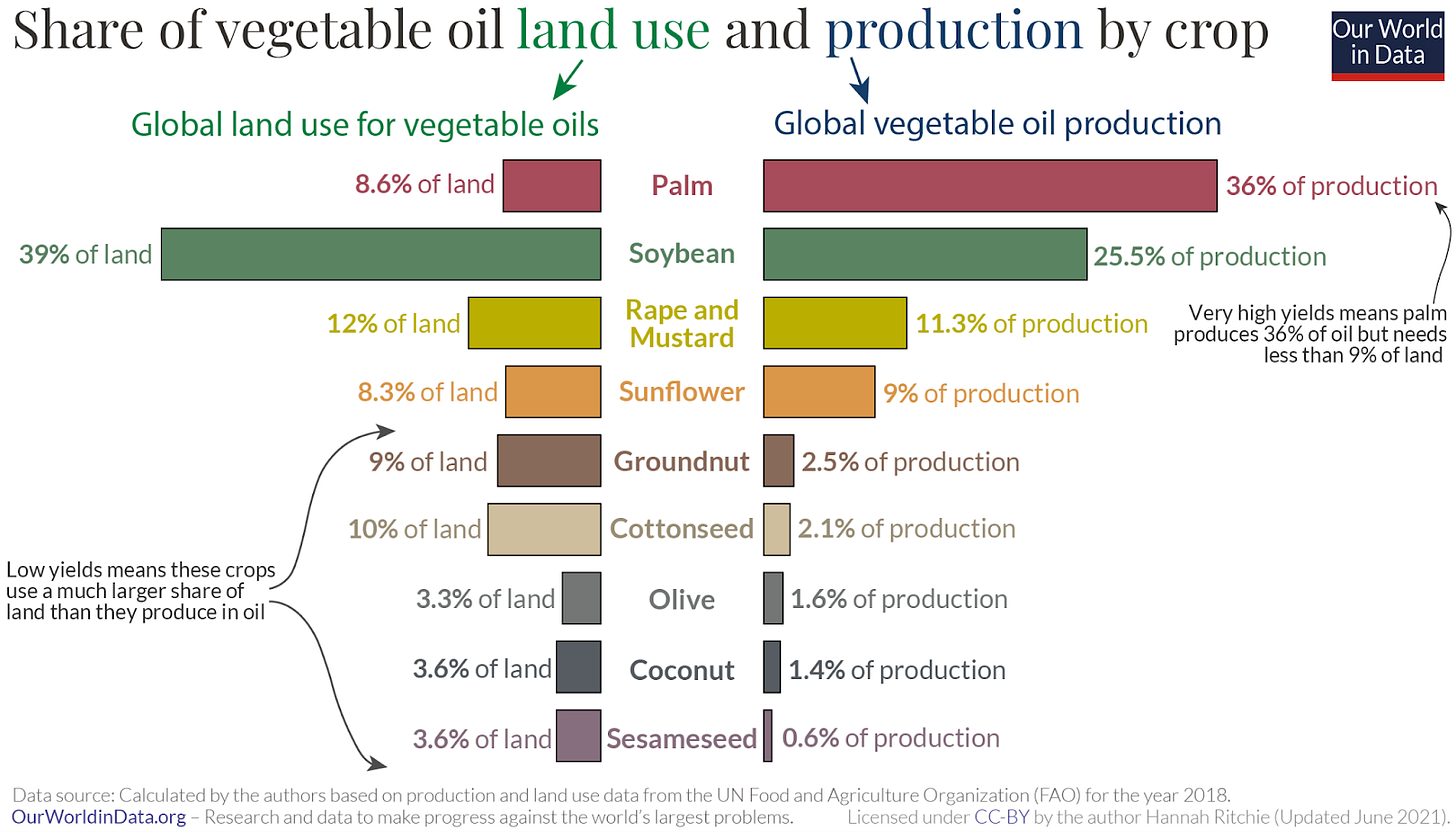

Here’s the complicated part: palm oil is incredibly efficient. “It produces over a third of the world’s oil but uses less than a tenth of croplands devoted to oil production,” according to Our World in Data. Switching to other oils would require even more land.

So once again, the issue isn’t palm oil itself, but where we grow it: on freshly cleared rainforest and carbon-rich peatlands, often for products where the oil adds little nutritional value.

In short, every cheap cookie baked with anonymous palm carries an invisible price tag paid in lost forests, carbon emissions, and endangered species.

So, is palm oil bad? That’s the wrong question.

The better one is: what does palm oil reveal?

Palm oil is a symbol of how food got optimised for scale—not health, not taste, not culture. It shows us what happens when an ingredient is engineered to be invisible, interchangeable, and everywhere at once.

That’s the real story. Not just about demonising a single ingredient, but understanding how it reflects the broader choices we’ve made about our food system.

Just Dropped

Do men lose weight faster than women?

Does refrigeration kill nutrition?

Everyone has an opinion on your body. But why?

Here’s how I got my cholesterol levels down

How to find a good therapist?

Longevity secrets: What I learned about preventing chronic diseases

Nutrition science is so confusing. That’s okay!